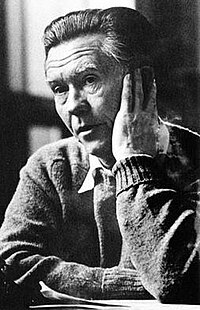

William Stafford (poet)

William Stafford | |

|---|---|

William Stafford | |

| Born | William Edgar Stafford January 17, 1914 Hutchinson, Kansas, USA |

| Died | August 28, 1993 (aged 79) Lake Oswego, Oregon, USA |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Period | 1962–1993 |

| Notable awards | National Book Award for Poetry (1963), Guggenheim Fellowship (1966), Western States Book Award (1992), Robert Frost Medal (1993) |

| Spouse | Dorothy Hope Frantz |

| Children | Kim Stafford, Kit Stafford, Barbara Stafford |

William Edgar Stafford (January 17, 1914 – August 28, 1993) was an American poet and pacifist. He was the father of poet and essayist Kim Stafford. He was appointed the twentieth Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1970.[1]

Early life

[edit]Background

[edit]Stafford was born in Hutchinson, Kansas, the oldest of three children in a highly literate family. During the Depression, his family moved from town to town in an effort to find work for his father. Stafford helped contribute to family income by delivering newspapers, working in sugar beet fields, raising vegetables, and working as an electrician's apprentice.

Stafford graduated from high school in the town of Liberal, Kansas[2] in 1933. After initially attending senior college, he received a B.A. from the University of Kansas in 1937. He was drafted into the United States armed forces in 1941 while pursuing his master's degree at the University of Kansas, but declared himself a pacifist. As a registered conscientious objector, he performed alternative service from 1942 to 1946 in the Civilian Public Service camps. The work consisted of forestry and soil conservation work in Arkansas, California, and Illinois for $2.50 per month. While working in California in 1944, he met and married Dorothy Hope Frantz, with whom he later had four children (Bret, who died in 1988; Kim, writer; Kit, artist; Barbara, artist). He received his M.A. from the University of Kansas in 1947. His master's thesis, the prose memoir Down In My Heart, was published in 1948 and described his experience in the forest service camps. He taught English for one academic semester (1947) to 11th graders (juniors) at Chaffey Union High School, Ontario, California. That same year he moved to Oregon to teach at Lewis & Clark College. In 1954, he received a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa. Stafford taught for one academic year (1955–1956) in the English department at Manchester College in Indiana, a college affiliated with the Church of the Brethren where he had received training during his time in Civilian Public Service.[3] The following year (1956–57), he taught at San Jose State in California, and the next year returned to the faculty of Lewis & Clark.

Career

[edit]One striking feature of his career is its late start. Stafford was 48 years old when his first major collection of poetry was published, Traveling Through the Dark,[4] which won the 1963 National Book Award for Poetry.[5] The title poem is one of his best-known works. It describes encountering a recently killed doe on a mountain road. Before pushing the doe into a canyon, the narrator discovers that she was pregnant and the fawn inside is still alive.

Stafford had a quiet daily ritual of writing, and his writing focuses on the ordinary. Paul Merchant, writing in the Oregon Encyclopedia, is gentle quotidian style to Robert Frost. Merchant states, "his poems are accessible, sometimes deceptively so, with a conversational manner that is close to everyday speech. Among predecessors whom he most admired are William Wordsworth, Thomas Hardy, Walt Whitman, and Emily Dickinson."[6] His poems are typically short, focusing on the earthy, accessible details appropriate to a specific locality. Stafford said this in a 1971 interview:

I keep following this sort of hidden river of my life, you know, whatever the topic or impulse which comes, I follow it along trustingly. And I don't have any sense of its coming to a kind of crescendo, or of its petering out either. It is just going steadily along.[7]

Stafford was a close friend and collaborator with poet Robert Bly. Despite his late start, he was a frequent contributor to magazines and anthologies and eventually published fifty-seven volumes of poetry. James Dickey called Stafford one of those poets "who pour out rivers of ink, all on good poems."[8] He kept a daily journal for 50 years, and composed nearly 22,000 poems, of which roughly 3,000 were published.[9]

In 1970, he was named Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, a position that is now known as Poet Laureate. In 1975, he was named Poet Laureate of Oregon; his tenure in the position lasted until 1990.[10] In 1980, he retired from Lewis & Clark College but continued to travel extensively and give public readings of his poetry. In 1992, he won the Western States Book Award for lifetime achievement in poetry.[11]

Personal life

[edit]Stafford died at his home in Lake Oswego, Oregon on August 28, 1993. The morning of his death he had written a poem containing the lines, "'You don't have to / prove anything,' my mother said. 'Just be ready / for what God sends.'"[12][13] In 2008, the Stafford family gave William Stafford's papers, including the 20,000 pages of his daily writing, to the Special Collections Department at Lewis & Clark College.

Kim Stafford, who serves as literary executor for the Estate of William Stafford, has written a memoir, Early Morning: Remembering My Father, William Stafford (Graywolf Press).

Bibliography

[edit]- Published Poetry Collections

- West of Your City, Talisman Press, 1960.

- Traveling through the Dark, Harper, 1962.

- The Rescued Year, Harper, 1965.

- Eleven Untitled Poems, Perishable Press, 1968.

- Weather: Poems, Perishable Press, 1969.

- Allegiances, Harper, 1970.

- Temporary Facts, Duane Schneider Press, 1970.

- Poems for Tennessee, (With Robert Bly and William Matthews) Tennessee Poetry Press, 1971.

- In the Clock of Reason, Soft Press, 1973.

- Someday, Maybe, Harper, 1973.

- That Other Alone, Perishable Press, 1973.

- Going Places: Poems, West Coast Poetry Review, 1974.

- The Earth, Graywolf Press, 1974.

- North by West, (With John Meade Haines) edited by Karen Sollid and John Sollid, Spring Rain Press, 1975.

- Braided Apart (With son, Kim Robert Stafford), Confluence, 1976.

- I Would Also Like to Mention Aluminum: Poems and a Conversation, Slow Loris Press, 1976.

- Late, Passing Prairie Farm: A Poem, Main Street Inc., 1976.

- The Design on the Oriole, Night Heron Press, 1977.

- Stories That Could Be True: New and Collected Poems, Harper, 1977.

- Smoke's Way (chapbook), Graywolf Press, 1978.

- All about Light, Croissant, 1978.

- A Meeting with Disma Tumminello and William Stafford, edited by Nat Scammacca, Cross-Cultural Communications, 1978.

- Passing a Creche, Sea Pen Press, 1978.

- Tuft by Puff, Perishable Press, 1978.

- Two about Music, Sceptre Press, 1978.

- Tuned in Late One Night, The Deerfield Press, 1978, The Gallery Press, 1978.

- The Quiet of the Land, Nadja Press, 1979.

- Around You, Your Horse & A Catechism, Sceptre Press, 1979.

- Absolution, Martin Booth, 1980.

- Things That Happen When There Aren't Any People, BOA Editions, 1980.

- Passwords, Sea Pen Press, 1980.

- Wyoming Circuit, Tideline Press, 1980.

- Sometimes Like a Legend: Puget Sound Country, Copper Canyon Press, 1981.

- A Glass Face in the Rain: New Poems, Harper, 1982.

- Roving across Fields: A Conversation and Uncollected Poems 1942–1982, edited by Thom Tammaro, Barnwood, 1983.

- Smoke's Way: Poems, Graywolf, 1983.

- Segues: A Correspondence in Poetry, (With Marvin Bell) David Godine, 1983.

- Listening Deep: Poems (chapbook), Penmaen Press, 1984.

- Stories and Storms and Strangers, Honeybrook Press, 1984.

- Wyoming, Ampersand Press, Roger Williams College, 1985.

- Brother Wind, Honeybrook Press, 1986.

- An Oregon Message, Harper 1987.

- You and Some Other Characters, Honeybrook Press, 1987.

- Annie-Over, (With Marvin Bell) Honeybrook Press, 1988.

- Writing the World, Alembic Press, 1988.

- A Scripture of Leaves, Brethren Press, 1989. Reprinted 1992.

- Fin, Feather, Fur, Honeybrook Press, 1989.

- Kansas Poems of William Stafford, edited by Denise Low, Woodley Press, 1990.

- How to Hold Your Arms When It Rains, Confluence Press, 1991.

- Passwords, HarperPerennial, 1991.

- The Long Sigh the Wind Makes, Adrienne Lee Press, 1991.

- History is Loose Again, Honeybrook Press, 1991.

- The Animal That Drank Up Sound (a children's book, illustrated by Debra Frasier), Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1992.

- Seeking the Way (with illuminations by Robert Johnson), Melia Press, 1992.

- My Name is William Tell, Confluence Press, 1992.

- Holding Onto the Grass, Honeybrook Press, 1992, reprinted, Weatherlight Press, 1994.

- Who Are You Really Wanderer?, Honeybrook Press, 1993.

- The Darkness Around Us Is Deep: Selected Poems of William Stafford, edited and with an introduction by Robert Bly, HarperPerennial, 1993.

- Learning to Live in the World: Earth Poems by William Stafford, Harcourt, Brace, & Company, 1994.

- The Methow River Poems, Confluence Press, 1995.

- Even In Quiet Places, Confluence Press, 1996.

- The Way It Is: New and Selected Poems, introduction by Naomi Shihab Nye, Graywolf Press, 1998.

- Another World Instead: The Early Poems of William Stafford, 1937–1947. Graywolf Press, 2008.

- Ask Me: 100 Essential Poems of William Stafford. Graywolf Press, 2013.

- Winterward. Tavern Books, 2013.

- Prose

- Down in My Heart (memoir). Elgin, Ill.: Brethren Publishing House, 1947. Reprint: Columbia, S.C.: Bench Press, 1985.

- Writing the Australian Crawl. Views on the Writer's Vocation (essays and reviews). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1978.

- You Must Revise Your Life (essays and interviews). Ann Arbor. University of Michigan Press, 1986.

- Every War Has Two Losers: William Stafford on Peace and War (daily writings, essays, interviews, poems). Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2003.

- The Answers Are Inside the Mountains: Meditations on the Writing Life (essays and interviews). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

- Crossing Unmarked Snow: Further Views on the Writer's Vocation (essays and interviews). University of Michigan Press, 1998.

- The Osage Orange Tree (fiction short story). Trinity University Press, 2014.

- Translations

- Poems by Ghalib. New York: Hudson Review, 1969. Translated by Stafford, Adrienne Rich and Ajiz Ahmad.

See also

[edit]- Lawson Fusao Inada, named state Poet Laureate in 2006

References

[edit]- ^ "Poet Laureate Timeline: 1961–1970". Library of Congress. 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ "William Stafford | Center for Great Plains Studies | Nebraska". www.unl.edu. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "Manchester University Archives -Faculty/Staff Boxes 46-48: Stafford, William- Faculty/Staff: William Stafford". www.manchester.edu. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ "Traveling Through the Dark Summary (Class 12)". Mero Notice. 2021-03-11. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ^ "National Book Awards – 1963". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-03.

(With acceptance speech by Stafford and essay by Eric Smith from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) - ^ Merchant, Paul (2014). "William Stafford (1914–1993)". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- ^ Username *. "Modern American Poetry". English.uiuc.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ "William Stafford". www.literarytraveler.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2000. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Beloit College".

- ^ See list of Oregon Poets Laureate, at < http://oregonpoetlaureate.org/history/>.

- ^ "Axe-Special Collections - William Stafford". library.pittstate.edu. Archived from the original on 18 February 1999. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "The Sacred Blur, William Stafford (1914-1993)". www.newsfromnowhere.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 1998. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "William Stafford - newsfromnowhere.com". www.newsfromnowhere.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2001. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- William Stafford, Richard Hugo, John Haines, William Matthews, Reg Saner, Richard Shelton, Gary Soto, and David Wagoner (1982). Wild, Peter and Graziano, Frank (ed.). New Poetry of the American West. Durango, CO: Logbridge-Rhodes. pp. 104. ISBN 978-0937406199.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) OCLC 8589531, 655452420, 610178960 (print and on-line)

External links

[edit]- William Stafford Archives website

- William Stafford Prize for Poetry

- William Stafford page at Academy of American Poets website

- William Young (Winter 1993). "William Stafford, The Art of Poetry No. 67". The Paris Review. Winter 1993 (129).

- Quotes about Stafford's writing style Archived 2004-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

- An Encounter with William Stafford by David Feela

- Friends of William Stafford

- Poems about Hutchinson, Kansas

- TTTD Productions Poetry Videos and DVDs featuring Poets Laureate William Stafford, Lawson Inada, etc.

- A Pacifist's Plainspoken Poetry, NPR interview

- Oregon Poet Laureate program, homepage

- [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7cjBZ4Nv-U&list=PL_uRBSjikfiwJDUTvddRDU6N14zYLlzH4&index=4 An Oregon Message: With William Stafford]

- 1914 births

- 1993 deaths

- American Christian pacifists

- American conscientious objectors

- 20th-century American poets

- American Poets Laureate

- American members of the Church of the Brethren

- Lewis & Clark College faculty

- National Book Award winners

- People from Hutchinson, Kansas

- People from Lake Oswego, Oregon

- Poets Laureate of Oregon

- University of Kansas alumni

- Poets from Oregon

- Members of the Civilian Public Service