Rings of Power

| Rings of Power | |

|---|---|

| First appearance | The Hobbit (1937: a magical ring) The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955: Rings of Power) |

| Created by | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | Magical rings |

The Rings of Power are magical artefacts in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, most prominently in his high fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings. The One Ring first appeared as a plot device, a magic ring in Tolkien's children's fantasy novel, The Hobbit; Tolkien later gave it a backstory and much greater power. He added nineteen other Great Rings, also conferring powers such as invisibility, that it could control, including the Three Rings of the Elves, Seven Rings for the Dwarves, and Nine for Men. He stated that there were in addition many lesser rings with minor powers. A key story element in The Lord of the Rings is the addictive power of the One Ring, made secretly by the Dark Lord Sauron; the Nine Rings enslave their bearers as the Nazgûl (Ringwraiths), Sauron's most deadly servants.

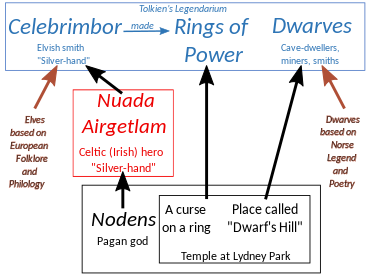

Proposed sources of inspiration for the Rings of Power range from Germanic legend with the ring Andvaranaut and eventually Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, to fairy tales such as Snow White, which features both a magic ring and seven dwarfs. One experience that may have been pivotal was Tolkien's professional work on a Latin inscription at the temple of Nodens; he was a god-hero linked to the Irish hero Nuada Airgetlám, whose epithet is "Silver-Hand", or in Elvish "Celebrimbor", the name of the Elven-smith who made the Rings of Power. The inscription contained a curse upon a ring, and the site was called Dwarf's Hill.

The Rings of Power have been described as symbolising the way that power conflicts with moral behaviour; Tolkien explores the way that different characters, from the humble gardener Sam Gamgee to the powerful Elf ruler Galadriel, the proud warrior Boromir to the Ring-addicted monster Gollum, interact with the One Ring. Tolkien stated that The Lord of the Rings was an examination of "placing power in external objects".[1]

Fictional history

[edit]

"But wherefore should Middle-earth remain for ever desolate and dark, whereas the Elves could make it as fair as Eressëa, nay even as Valinor? And since you have not returned thither, as you might, I perceive that you love this Middle-earth, as do I. Is it not then our task to labour together for its enrichment, and for the raising of all the Elven-kindreds that wander here untaught to the height of that power and knowledge which those have who are beyond the Sea?"

— J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, "The Rings of Power and the Third Age"

The Rings of Power were forged by the Elven-smiths of the Noldorin settlement of Eregion.[T 1] Best-known were the twenty Great Rings, which conferred powers including invisibility, but many lesser rings with minor powers were also created at that time. The smiths were led by Celebrimbor, the grandson of Fëanor, the greatest craftsman of the Noldor, working with Dwarves from Khazad-dûm (Moria) led by his friend Narvi. Sauron, powerful and ambitious, but humiliated by the fall of his evil master Morgoth at the end of the First Age, had evaded the summons of the godlike Valar to surrender and face judgment; he chose to remain in Middle-earth and seek dominion over its people.[T 2] In the Second Age, he arrived disguised as a handsome emissary of the Valar named Annatar, the Lord of Gifts, offering the knowledge to transform Middle-earth with the light of Valinor, the home of the Valar.[T 1] He was shunned by the Elven leaders Gil-galad and Elrond in Lindon, but managed to persuade the Noldorin Elves of Eregion.[T 2] With Sauron's help, they learnt to forge Rings of Power, creating the Seven and the Nine. While Celebrimbor created a set of Three on his own, Sauron left for Mordor and forged the One Ring, a master ring to control all the others, in the fires of Mount Doom.[T 1]

When the One Ring was made using the Black Speech, the Elves immediately became aware of Sauron's true motive to control the other Rings.[T 2] When Sauron set the completed One Ring upon his finger, the Elves quickly hid their rings.[T 2] Celebrimbor entrusted one of the Three to Galadriel and sent the other Two to Gil-galad and Círdan.[T 3][T 4] In an attempt to seize all the Rings of Power for himself, Sauron waged an assault upon the Elves.[T 2] He destroyed Eregion and captured the Nine. Under torture, Celebrimbor revealed where the Seven were, but refused to reveal the Three.[T 5]

Toward the end of the Second Age, the Númenóreans took Sauron prisoner.[T 2] Sauron however managed to corrupt the Men of Númenor, leading to their civilisation's eventual downfall.[T 2] The exiled Númenóreans who survived, led by Elendil and his sons Isildur and Anárion, established the realms of Arnor and Gondor.[T 2] Together with the Elves of Lindon, they formed the last alliance against Sauron and emerged victorious.[T 2] Isildur cut the One Ring from Sauron's hand and kept it, refusing to destroy it; he was later killed in an ambush, and the Ring was lost for centuries.[T 6] During this time, the Elves were able to use the Three Rings, while the Nine given to the leaders of Men corrupted their wearers and turned them into the Nazgûl.[T 7] The Seven given to the Dwarves failed to subject them directly to Sauron's will but ignited a sense of avarice within them.[T 2] Over the years, Sauron sought to recapture the Rings, primarily the One, but was only successful in recovering the Nine and three of the Seven.[T 6]

During the Third Age, the One Ring is discovered by Bilbo Baggins (in The Hobbit). At the start of The Lord of the Rings, the Wizard Gandalf explains the One Ring's history to Bilbo's heir Frodo, and recites the Rhyme of the Rings. A Fellowship is formed to destroy it, led by Frodo.[T 8][T 6][T 7] Following the successful destruction of the One Ring and the fall of Sauron, the power of the rings fades. While the Nine are destroyed, the Three are rendered powerless; their bearers leave Middle-earth for Valinor at the end of the Third Age, inaugurating the Dominion of Men.[2][T 9][T 2]

Description

[edit]

Three Rings for the Elven-kings under the sky,

Seven for the Dwarf-lords in their halls of stone,

Nine for Mortal Men doomed to die,

One for the Dark Lord on his dark throne;

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.

One Ring to rule them all, one Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them;

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.

As observed by Saruman, each Ring of Power was adorned with its "proper gem", except for the One Ring, which was unadorned.[T 7]

The One

[edit]Unlike the other great rings, the One was created as an unadorned gold band similar in appearance to the lesser rings, though it bore Sauron's incantation, the Ring Verse, in the Black Speech; it became visible only when heated, whether by fire or by Sauron's hand.[T 6] As the other Rings were made under the influence of Sauron, the power of all the Rings depended on the One Ring's survival.[2][T 9] To make the One Ring, Sauron had to put almost all his power into it—when worn, it enhanced his power; unworn, it remained aligned to him unless another seized it and took control of it.[T 10] A prospective possessor could, if sufficiently strong, overthrow Sauron and usurp his place; but they would become as evil as he.[T 10] As the One was made in the fires of Mount Doom, it could only be unmade there.[T 7] Sauron, being evil, never imagined that anyone might try to destroy the One Ring, as he imagined that anyone bearing it would be corrupted by it.[T 10]

The Three

[edit]

Named after the three elements of fire, water, and air, the Three were the last to be made before Sauron's solo creation of the One. Although Celebrimbor forged the Three Rings alone in Eregion, they were moulded by Sauron's craft and were bound to the One.[T 1] Only after Sauron's defeat, when the One Ring was cut from his finger at the end of the Second Age, did the Elves begin to actively use the Three to ward off the decay brought by time. Even then, the Rings could be worn without being seen.[T 2] After the One Ring, they are the most powerful of the twenty Rings of Power.[T 11] They are:

- Narya (the Ring of Fire, the Red Ring), from Quenya nár, "fire",[T 12] was set with a ruby. Its metal is not stated. It gave its wielder resistance to the weariness of time, and evoked hope and courage in others. Its final bearer was the Wizard Gandalf, who received it from Círdan at the Grey Havens during the Third Age. [T 4]

- Nenya (the Ring of Water, the White Ring, the Ring of Adamant), from Quenya nén, "water",[T 13] was made of mithril and set with a "shimmering white stone". Galadriel used it to protect and preserve the realm of Lothlórien.[T 2] "Adamant" means both a type of stone, usually a diamond, and "stubbornly resolute", a description that equally well suits the quality of Galadriel's resistance to Sauron.[3]

- Vilya (the Ring of Air, the Blue Ring), from Quenya vilya, "air",[T 14] was the mightiest of the Three. It was made of gold and set with a sapphire. Elrond inherited Vilya from Gil-galad and used it to safeguard Rivendell.[T 2]

The Seven

[edit]Sauron recovered the Seven Rings from information provided by Celebrimbor, and gave them to the leaders of the seven kindreds of the Dwarves: Durin's Folk (Longbeards), Firebeards, Broadbeams, Ironfists, Stiffbeards, Blacklocks, and Stonefoots,[4] though a tradition of Durin's Folk claimed that Durin received his ring from the Elven-smiths.[T 15][T 1] Over the years, Sauron was able to recover only three of the Seven rings from the Dwarves. The last of the three was seized from Thráin II during his captivity in Dol Guldur. Gandalf recounts to Frodo that the remaining four were consumed by dragons.[T 6] Before the outbreak of the War of the Ring, an envoy from Sauron attempted to bribe Dain II Ironfoot of the Lonely Mountain with the three surviving rings and the lost realm of Moria in exchange for information leading to the recovery of the One Ring, but Dain refused.[T 7]

The Nine

[edit]Sauron gave Nine of the Rings of Power to leaders of Men, who became "mighty in their day, kings, sorcerers, and warriors of old". They gained unending lifespans, and the ability to see things in worlds invisible to mortal Men.[T 2] One by one, the Men fell to the power of the One Ring; by the end of the Second Age, all nine had become invisible ring-wraiths – the Nazgûl, Sauron's most terrible servants. In particular, they helped him search for the One Ring, to which they were powerfully attracted.[T 16]

Powers

[edit]| Type of Ring | Powers granted | Effects on bearer |

|---|---|---|

| Ruling Ring | Invisibility, extended lifespan, control, knowledge of all other Rings | Corruption to evil |

| Elven-Rings | To heal and preserve | Nostalgia, procrastination |

| Dwarf-Rings | To gain wealth | Greed, anger |

| Rings for Men | Invisibility, extended lifespan, terror | Enslavement, fading to permanent invisibility |

The Rings of Power were made using the craft taught by Sauron to give their wearers "wealth and dominion over others". Each Ring enhances the "natural power" of its possessor, thus approaching its "magical aspect", which can be "easily corruptible to evil and lust of domination".[T 17] Gandalf explains that a Ring of Power is self-serving and can "look after itself": the One Ring, in particular, can "slip off treacherously" to return to its master Sauron, betraying its bearer when an opportunity arrives.[T 6] As the Ruling Ring, the One enables a sufficiently powerful bearer to perceive what is done using the other rings and to govern the thoughts of their bearers.[T 2] To use the One Ring to its full extent, the bearer needs to be strong and train their will to the domination of others.[T 18]

A mortal Man or Hobbit who takes possession of a Ring of Power can manifest its power, becoming invisible and able to see things that are normally invisible, as the bearer is partly transported into the spirit world.[T 6][5][T 17] However, they also "fade"; the Rings unnaturally extend their life-spans, but gradually transform them into permanently invisible wraiths.[T 19][T 6][T 20] The Rings affect other beings differently. The Seven are used by their Dwarven bearers to increase their treasure hoards, but they do not gain invisibility, and Sauron was unable to bend the Dwarves to his will, instead only amplifying their greed and anger.[T 2] Tom Bombadil, the only person unaffected by the power of the One Ring, could both see its wearer and remained visible when he wore it.[T 21]

Unlike the other Rings, the main purpose of the Three is to "heal and preserve", as when Galadriel used Nenya to preserve her realm of Lothlórien over long periods.[1] The Elves made the Three Rings to try to halt the passage of time, or as Tolkien had Elrond say, "to preserve all things unstained". This was seen most clearly in Lothlórien, which was free of both evil and the passage of time.[6][7] The Three do not make their wearers invisible.[T 18] The Three had other powers: Narya could rekindle hearts with its fire and inspire others to resist tyranny, domination, and despair; Nenya had a secret power in its water that protected from evil; while Vilya healed and preserved wisdom in its element of air.[T 2]

Inspiration

[edit]Nodens

[edit]The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey thought that Tolkien's work on a Latin inscription at a Roman temple at Lydney Park was a "pivotal" influence, combining as it did a god-hero, a ring, dwarves, and a silver hand. The god-hero was Nodens, whom Tolkien traced to the Irish hero Nuada Airgetlám, "Nuada of the Silver-Hand", and the inscription carried a curse on a stolen ring.[T 22][8] "Silver-Hand" is the English translation of "Celebrimbor", the Elven-smith who made the Rings of Power, in association with the Dwarven-smith Narvi. The temple was at a place called Dwarf's Hill.[8][9][10][11]

Ring of Gyges

[edit]Magical rings occur in classical legend, in the form of the Ring of Gyges in Plato's Republic. It grants the power of invisibility to its wearer, creating a moral dilemma, enabling people to commit injustices without fearing they would be caught.[12] In contrast, Tolkien's One Ring actively exerts an evil force that destroys the morality of the wearer.[T 6]

-

The shepherd Gyges of Plato's Republic finds the magic ring, setting up a moral dilemma.[12] Ferrara, 16th century

Scholars including Frederick A. de Armas note parallels between Plato's and Tolkien's rings.[12][13] De Armas suggests that both Bilbo and Gyges, going into deep dark places to find hidden treasure, may have "undergone a Catabasis", a psychological journey to the Underworld.[12]

| Story element | Plato's Republic | Tolkien's Middle-earth |

|---|---|---|

| Ring's power | Invisibility | Invisibility, and corruption of the wearer |

| Discovery | Gyges finds ring in a deep chasm | Bilbo finds ring in a deep cave |

| First use | Gyges ravishes the Queen, kills the King, becomes King of Lydia (a bad purpose) |

Bilbo puts ring on by accident, is surprised Gollum does not see him, uses it to escape danger (a good purpose) |

| Moral result | Total failure | Bilbo emerges strengthened |

The Tolkien scholar Eric Katz writes that "Plato argues that such [moral] corruption will occur, but Tolkien shows us this corruption through the thoughts and actions of his characters".[14] Plato argues that immoral life is no good as it corrupts one's soul. So, Katz states, according to Plato a moral person has peace and happiness, and would not use a Ring of Power.[14] In Katz's view, Tolkien's story "demonstrate[s] various responses to the question posed by Plato: would a just person be corrupted by the possibility of almost unlimited power?"[14] The question is answered in different ways: the monster Gollum is weak, quickly corrupted, and finally destroyed; Boromir, son of the Steward of Gondor, begins virtuous but like Plato's Gyges is corrupted "by the temptation of power"[14] from the Ring, even if he wants to use it for good, but redeems himself by defending the hobbits to his own death; the "strong and virtuous"[14] Galadriel, who sees clearly what she would become if she accepted the ring, and rejects it; the immortal Tom Bombadil, exempt from the Ring's corrupting power and from its gift of invisibility; Sam who in a moment of need faithfully uses the ring, but is not seduced by its vision of "Samwise the Strong, Hero of the Age"; and finally Frodo who is gradually corrupted, but is saved by his earlier mercy to Gollum, and Gollum's desperation for the Ring. Katz concludes that Tolkien's answer to Plato's "Why be moral?" is "to be yourself".[14]

Germanic legend and fairy tale

[edit]Tolkien was certainly influenced by the Germanic legend: Andvaranaut is a magical ring that can give its wielder wealth, while Draupnir is a self-multiplying ring that holds dominion over all the rings it creates. Richard Wagner's opera series Der Ring des Nibelungen adapted Norse mythology to provide a magical but cursed golden ring.[15] Tolkien denied any connection, but scholars agreed that Wagner's Ring powerfully influenced Tolkien.[16] The scholar of religion Stefan Arvidsson writes that Tolkien's ring differs from Wagner's in being concerned with power for its own sake and that he turned one ring into many, an echo of the self-multiplying ring.[16]

"Magic rings are a frequent motif in fairy tales; they confer powers such as invisibility or flight; they can summon wish-granting djinns and dwarves", writes the Tolkien and feminist scholar Melanie Rawls. She adds that they "identify the enchanted princess, hold the tiny golden key to the secret room, give one the power to transform oneself into any form — animal, vegetable, or mineral: duck, lake, rock or tree on a plain, and so escape the ogre."[17] As Tolkien was well acquainted with fairy tales like The Brothers Grimm's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Jeanette White from Comic Book Resources suggested that his choice "to gift seven rings of power to the Dwarf Lords of the seven kingdoms is probably no accident".[18][19]

The nine rings for Mortal Men match the number of the Nazgûl. Edward Pettit, in Mallorn, states that nine is "the commonest 'mystic' number in Germanic lore". He quotes the "Nine Herbs Charm" from the Lacnunga, an Old English book of spells, suggesting that Tolkien may have made multiple uses of such spells to derive attributes of the Nazgûl:[20]

against venom and vile things

and all the loathly ones,

that through the land rove,

...

against nine fugitives from glory,

against nine poisons and

against nine flying diseases.

Analysis

[edit]Plot device to core element

[edit]The One Ring first appeared in Tolkien's children's fantasy The Hobbit in 1937 as a plot device, a mysterious magic ring that the titular character had stumbled upon, but its origin was left unexplained.[21] Following the novel's success, Tolkien was persuaded by his publishers Allen & Unwin to write a sequel.[T 23][22] Intending to give Bilbo another adventure, he instead devised a background story around the Ring with its power of invisibility, forming a framework for the new work.[T 24] He tied the Ring to mythical elements from the unfinished manuscripts for The Silmarillion to create an impression of depth in The Lord of the Rings.[23] Gollum's characterisation in The Hobbit was revised for the second edition to bring it into line with his portrayal in The Lord of the Rings as a being addicted to the One Ring.[T 25]

Tolkien's conception of Ring-lore was closely linked to his development of the One Ring.[24] He initially made Sauron instrumental in forging the Rings.[T 26] He then briefly considered having Fëanor, creator of the Silmarils, forge the Rings of Power, under the influence of Morgoth, the first Dark Lord. He settled on Celebrimbor, a descendant of Fëanor, as the Ring's principal maker, under the tutelage of Sauron, Morgoth's chief servant.[T 27] While writing the lore behind the One Ring, Tolkien struggled with giving the Elven rings a "special status" – somehow linked to the One, and thus endangered by it, but also "unsullied", having no direct connection with Sauron.[25] By the time he was writing the chapter "The Mirror of Galadriel", Tolkien had decided that the Seven and the Nine were made by the Elven-smiths of Eregion under Sauron's guidance and that the Three were made by Celebrimbor alone.[25] He considered setting the Three free from the One when it was destroyed but dropped the idea.[25] Tolkien's posthumous works, including The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales and The History of Middle-earth offer further glimpses of the creation of the Rings.[T 1][T 28][T 29]

Jason Fisher, writing in Tolkien Studies, notes that Tolkien developed the names, descriptions and powers of the Three Rings late and slowly through many drafts of his narratives. In Fisher's view, Tolkien found it difficult to work these Rings both into the existing story of the One Ring, and into the enormous but Ring-free legendarium.[26] Some of the descriptions, such as that Vilya was the mightiest of the Three, and that Narya was called "The Great", were added at the galley proof stage, just before printing.[26][27] The Rings had earlier been named Kemen, Ëar, and Menel, meaning the Rings of Earth, Sea, and Heaven.[28]

According to Johann Köberl, Tolkien struggled with the notion of a "special status" for the Elven-Rings, and considered having The Three set free when the One Ring was destroyed.[25] In an unused draft by Tolkien, Galadriel counselled Celebrimbor to destroy all the Rings when Sauron's deception was revealed, but when he could not bear to ruin them, she suggested that the Three be hidden.[T 4][T 30] According to Unfinished Tales, at the start of the War of the Elves and Sauron, Celebrimbor gave both Narya and Vilya to Gil-galad, High King of the Noldor. Gil-galad later entrusted Vilya to his lieutenant Elrond, and Narya to Círdan the Shipwright, Lord of the Havens of Mithlond and leader of the Falathrim or "People of the Shore".[29] Tolkien suggested that Sauron did not discover where the Three were hidden, though he guessed that they were given to Gil-galad and Galadriel.[T 30] In the published The Lord of the Rings, Gil-galad received only Vilya, while Círdan was the direct recipient of Narya from Celebrimbor.

Tolkien noted in his letters that the primary power of the Three was to "the prevention and slowing of decay", which appealed to the Elves in their pursuit of preserving what they loved in Middle-earth.[1][T 31] As changeless beings in a changing world, the Elves who remained in Middle-earth relied on the Three to delay the inevitable rise of the Dominion of Men.[1][T 32][T 18] Tolkien explained that the Elves can only be immortal as long as the world endures, leading them to be concerned with burdens of deathlessness in time and change. Since they wanted the bliss and perfect memory of Valinor, yet to remain in Middle-earth with their prestige as the fairest, as opposed to being at the bottom of the hierarchy in the Undying Lands, they became obsessed with "fading".[T 33]

Power and morality

[edit]According to the scholars of philosophy Gregory Bassham and Eric Bronson, the Rings of Power can be seen as a modern representation of the relationship between power and morality, since it portrays an idea that "absolute power is in conflict with behaviour that respects the wishes and needs of others".[5] They also observed that several of Tolkien's characters have responded in different ways when faced with the possibility of possessing the One Ring—characters such as Samwise Gamgee and Galadriel have rejected it; Boromir and Gollum, were seduced by its power; and Frodo Baggins, though in limited use, ultimately succumbs to it; while Tom Bombadil can transcend its power entirely.[5] They also noted that for Tolkien, the crucial moment of each character in the story is the moment in which they are tempted to use a Ring, a choice that will determine their fate.[30] The science fiction author Isaac Asimov described the Rings of Power as symbols of industrial technology.[31][32] While Tolkien denied that The Lord of the Rings was an allegory, he stated that it could be applied to situations and described it as an examination of "placing power in external objects".[1]

Catholicism

[edit]Gwyneth Hood, writing in Mythlore, explores two Catholic elements in the story of the Three Rings: the angelic and sacrificial aspects of the Elves in the War of the Ring. To the Hobbits of the Fellowship of the Ring, the bearers of the Elven-Rings appear as angelic messengers, offering wise counsel. To save Middle-earth, they have to accept the plan to destroy the One Ring, and with it, the power of the Three Rings, which embody much of their own power. Hood notes that while Gandalf, as one of the supernatural Maiar sent from Valinor, is "remarkably unlike an elf",[33] he is the character who most closely combines the angelic and the sacrificial among the wielders of the Three Rings.[33] The poet W. H. Auden, an early supporter of Lord of the Rings, wrote in the Tolkien Journal that good triumphs over evil in the War of the Ring, but the Three Rings lose their power, as Galadriel had prophesied: "Yet if you succeed, then our power is diminished, and Lothlórien will fade, and the tides of time will sweep it away".[34] Hood further writes that Tolkien was suggesting technology, such as the making of Rings of Power, is in itself neither good nor evil; both the Elves and Sauron (with his armies of orcs) use that technology, as they also both make and wear swords and mail armour, and shoot with bows.[33]

In adaptations

[edit]

Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated film The Lord of the Rings begins with the forging of the Rings of Power and the events of the War of the Last Alliance against Sauron, all of which are animated in a silhouette against a red background using rotoscoping.[35]

The forging of the Rings of Power opens the prologue of Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings film series in the 2001 The Fellowship of the Ring. The Three Elven Rings are shown being cast using a cuttlebone mould, an ancient casting technique. These were given to Gil-galad (portrayed by Mark Ferguson), Círdan (Michael Elsworth), and Galadriel (Cate Blanchett).[36] The Tolkien illustrator Alan Lee, employed as a conceptual designer for the films, had a cameo as one of the nine human Ring-bearers who later became the Nazgûl. Sauron (Sala Baker) is seen forging the One Ring at the chamber of Mount Doom.[37] The One Ring was shown to have the ability to adjust in size to the finger of its wearer, such as when it became smaller to fit Isildur (Harry Sinclair). In the extended version, Galadriel properly introduces Nenya, the Ring of Adamant, to Frodo. In the concluding film, The Return of the King (2003), the final wearers of the Three Rings—Gandalf (Ian McKellen), Elrond (Hugo Weaving), and Galadriel, appear openly at the Grey Havens wearing the Three, with Galadriel proclaiming the end of its power and the beginning of the Dominion of Men.[38]

Four Rings of Power appeared in Jackson's The Hobbit film series. In An Unexpected Journey (2012), the One Ring was found by Bilbo Baggins (portrayed by Martin Freeman).[39] In the extended version of the succeeding film The Desolation of Smaug (2013), Gandalf discovers that Sauron took the Ring of Thrór (a Dwarf-Lord) from Thráin (Antony Sher), who revealed in a flashback scene his possession of the Ring during a siege of Moria.[40] In the concluding film The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), Galadriel (Blanchett) reveals Nenya in rescuing Gandalf (McKellen) from Sauron (Benedict Cumberbatch), aided by Saruman (Christopher Lee) and Elrond (Weaving), who is wearing Vilya, the Ring of Air.[41]

In the 2014 video game Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor, the wraith-like spirit of Celebrimbor (fused with the body of the Ranger Talion) recalls how Sauron had deceived him into forging the Rings of Power.[42] In the sequel, Middle-earth: Shadow of War, Celebrimbor forges a new Ring of Power unsullied by Sauron's influence.[43]

The 2022 television series The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power depicts the forging of the Rings of Power.[44]

See also

[edit]- The Palantíri: indestructible crystal stones that enable their users to communicate with users of the other stones

- The Silmarils: three jewels containing the light of the Two Trees of Valinor and the chief objects of The Silmarillion

References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Tolkien 1980, "The History of Galadriel and Celeborn"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Tolkien 1977, p. 298, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix B: "The Third Age"

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1980, "The History of Galadriel and Celeborn": The original published edition of The Lord of the Rings states that Gil-galad and Círdan each received a Ring of Power, though in his subsequent works Gil-galad received both and later gave one to Círdan.

- ^ Tolkien 1980, "The History of Galadriel and Celeborn": Christopher Tolkien notes that though it is implied that Sauron had taken possession of the Seven, there is no text detailing how those came into possession of the Dwarves, and the Dwarves of Moria maintained that their ring had come directly from Celebrimbor.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 2 "The Shadow of the Past"

- ^ a b c d e Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 2 "The Council of Elrond"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, ch. 5 "Riddles in the Dark"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 9 "The Grey Havens"

- ^ a b c Carpenter 2023, Letter #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- ^ Tolkien (1977), "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age": "Now these were the Three that had last been made, and they possessed the greatest powers"

- ^ Tolkien (1987), entry "nar"

- ^ Tolkien (1987), entry "nen"

- ^ Tolkien (1955), "Writing", "The Fëanorian Letters"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix A: III. "Durin's Folk"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix B "The Tale of Years"

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, Letter #121 to Allen & Unwin, 13 July 1949

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 7 "The Mirror of Galadriel"

- ^ Tolkien 1988, p. 78, "Of Gollum and the Ring"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 2, ch. 1 "Many Meetings"

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 7 "In the House of Tom Bombadil"

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R., "The Name Nodens", Appendix to "Report on the excavation of the prehistoric, Roman and post-Roman site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire", Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, 1932; also in Tolkien Studies: An Annual Scholarly Review, Vol. 4, 2007

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letter #19 to Stanley Unwin, 16 December 1937

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letter #21 to Allen & Unwin, 1 February 1938

- ^ Tolkien 1937: In the first published edition of The Hobbit, Gollum is portrayed as less obsessed with the One Ring, even offering it as a prize to Bilbo Baggins.

- ^ Tolkien 1989, p. 155

- ^ Tolkien 1989, p. 255

- ^ Tolkien 1988, ch. 3 "Of Gollum and the Ring"

- ^ Tolkien 1989, chs. 6, 7 "The Council of Elrond" (parts 1 & 2)

- ^ a b Tolkien (1980), The History of Galadriel and Celeborn

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letter #121 to Allen & Unwin, 13 July 1949

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letter #154 to Naomi Mitchison, 25 September 1954

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letter #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

Secondary

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Bassham & Bronson 2013, pp. 23–25.

- ^ a b Drout 2006, p. 573.

- ^ Hammond & Scull 2005, p. 324.

- ^ Strachan & Moseley 2017, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Bassham & Bronson 2013, p. 6-7

- ^ Aldrich, Kevin (1988). "The Sense of Time in J.R.R. Tolkien's 'The Lord of the Rings'". Mythlore. 15 (1). article 1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Brin, David (2008). Through Stranger Eyes: Reviews, Introductions, Tributes & Iconoclastic Essays. Nimble Books. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-934840-39-9.

- ^ a b c Anger, Don N. (2013) [2007]. "Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 563–564. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Lyons 2004, p. 63.

- ^ Armstrong, Helen (May 1997). "And Have an Eye to That Dwarf". Amon Hen: The Bulletin of the Tolkien Society (145): 13–14.

- ^ Bowers 2019, pp. 131–132.

- ^ a b c d e de Armas, Frederick A. (1994). "Gyges' Ring: Invisibility in Plato, Tolkien and Lope de Vega". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 3 (3/4): 120–138. JSTOR 43308203.

- ^ Neubauer, Lukasz. Less Consciously at First but More Consciously in the Revision: Plato's Ring as a Putative Source of Inspiration for Tolkien's Ring of Power. pp. 217–246. in Williams 2021

- ^ a b c d e f Katz, Eric (2003). "The Rings of Tolkien and Plato: Lessons in Power, Choice, and Morality". In Bassham, Gregory; Bronson, Eric (eds.). The Lord of the Rings and Philosophy: One Book to Rule Them All. Open Court. pp. 5–20. ISBN 978-0-8126-9545-8. OCLC 863158193.

- ^ Simek 2005, pp. 165, 173

- ^ a b Arvidsson, Stefan (2010). "Greed and the Nature of Evil: Tolkien versus Wagner" (PDF). Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. 22 (2). article 7. doi:10.3138/jrpc.22.2.007.

- ^ Rawls, Melanie (1984). "The Rings of Power". Mythlore. 11 (2). Article 5.

- ^ White, Jeannette (20 February 2021). "Are Lord of the Rings and Disney's Snow White Part of the Same Universe?". CBR. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Grundhauser, Eric (25 April 2017). "The Movie Date That Solidified J.R.R. Tolkien's Dislike of Walt Disney". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Pettit, Edward (2002). "J.R.R. Tolkien's use of an Old English charm". Mallorn (40): 39–44.

- ^ Köberl 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Köberl 2006, p. 1.

- ^ Rérolle 2012.

- ^ Drout 2006, p. 572.

- ^ a b c d Köberl 2006, p. 16

- ^ a b Fisher, Jason (2008). "Three Rings for—Whom Exactly? And Why?: Justifying the Disposition of the Three Elven Rings". Tolkien Studies. 5: 99–108. doi:10.1353/tks.0.0015. S2CID 171012566.

- ^ Hammond & Scull 2005, pp. 670–676.

- ^ Hammond & Scull 2005, pp. 670–671.

- ^ Dickerson, Matthew (2013) [2007]. "Elves: Kindreds and Migrations". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Bassham & Bronson 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Asimov 1996, p. 155, Concerning Tolkien.

- ^ Bassham & Bronson 2013, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Hood, Gwyneth (1993). "Nature and Technology: Angelic and Sacrificial Strategies in Tolkien's 'The Lord of the Rings'". Mythlore. 19 (4). article 2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Auden, W. H. (1967). "Good and Evil in 'The Lord of the Rings'". Tolkien Journal. 3 (1): 5–8. JSTOR 26807102.

- ^ Gilkeson 2018.

- ^ Pak, Jaron (24 July 2019). "The most powerful elves in Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings". Looper.com. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "Interview: December 16, 2005". The Book Report, Inc. 16 December 2005. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Elvy, Craig (8 November 2019). "Lord Of The Rings: What Happened To The OTHER Rings Of Power". Screen Rant. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "Gollum and Bilbo Meet in New Clip From The Hobbit". CraveOnline. 12 December 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug Extended Edition Scene Guide". TheOneRing.net. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel (19 December 2014). "The Tolkien Nerd's Guide to "The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies"". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Beck, Kellen (9 June 2017). "There's a new ring of power in Tolkien's 'Lord of the Rings' universe". Mashable. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Kain, Erik (27 February 2017). "New Ring Of Power Probably A Bad Idea In 'Middle-earth: Shadow of War'". Forbes. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Joe Otterson (19 January 2022). "'Lord of the Rings' Amazon Series Reveals Full Title in New Video". Variety.

Sources

[edit]- Asimov, Isaac (1996). Magic: The Final Fantasy Collection. New York: Harper Prism. ISBN 0-061-05205-1.

- Bassham, Gregory; Bronson, Eric (2013). The Lord of the Rings and Philosophy: One Book to Rule Them All. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-812-69806-0.

- Bowers, John M. (2019). Tolkien's Lost Chaucer. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-884267-5.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Drout, Michael (2006). Drout, Michael D.C (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203961513. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- Gilkeson, Austin (13 November 2018). "Ralph Bakshi's The Lord of the Rings Brought Tolkien from the Counterculture to the Big Screen". Tor.com. Tor Books. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2005). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-720907-1.

- Köberl, Johann. "The Lord of the Rings: Genesis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

- Lyons, Mathew (2004). There and Back Again: In the Footsteps of J. R. R. Tolkien. London: Cadogan Guides. ISBN 978-1-8601-1139-6.

- Rérolle, Raphaëlle (5 December 2012). "My Father's 'Eviscerated' Work – Son Of Hobbit Scribe J.R.R. Tolkien Finally Speaks Out". Le Monde/Worldcrunch. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013.

- Simek, Rudolf (2005). Mittelerde: Tolkien und die germanische Mythologie [Middle-earth: Tolkien and the Germanic Mythology] (in German). C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3406528378.

- Strachan, Jackie; Moseley, Jane (2017). The Order of Things: How hierarchies help us make sense of the world. United Kingdom: Hachette. ISBN 978-1-472-13991-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1989). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Treason of Isengard. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-51562-4.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1988). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Return of the Shadow. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-49863-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Part 3: "The Etymologies". ISBN 0-395-45519-7.

- Williams, Hamish, ed. (2021). Tolkien and the Classical World. Zurich. ISBN 978-3-905703-45-0. OCLC 1237352408.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

![The shepherd Gyges of Plato's Republic finds the magic ring, setting up a moral dilemma.[12] Ferrara, 16th century](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8a/Der_Ring_des_Gyges_%28Ferrara_16_Jh%29.jpg/369px-Der_Ring_des_Gyges_%28Ferrara_16_Jh%29.jpg)