Francesca da Rimini

Francesca da Rimini[a] or Francesca da Polenta[a] (died between 1283 and 1286)[1] was an Italian medieval noblewoman of Ravenna, who was murdered by her husband, Giovanni Malatesta, upon his discovery of her affair with his brother, Paolo Malatesta. She was a contemporary of Dante Alighieri, who portrayed her as a character in the Divine Comedy.

Life and death

[edit]Daughter of Guido I da Polenta of Ravenna, Francesca was wedded in or around 1275 to the brave, yet crippled Giovanni Malatesta (also called Gianciotto or "Giovanni the Lame"), son of Malatesta da Verucchio, lord of Rimini.[2] The marriage was a political one; Guido had been at war with the Malatesta family, and the marriage of his daughter to Giovanni was a way to secure the peace that had been negotiated between the Malatesta and the Polenta families. While in Rimini, she fell in love with Giovanni's younger brother, Paolo. Though Paolo, too, was married, they managed to carry on an affair for some ten years, until Giovanni ultimately surprised them in Francesca's bedroom some time between 1283 and 1286, killing them both.[3][4]

In Dante's Divine Comedy

[edit]

Francesca appears as a character in Dante's Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy, where she is the first soul damned in Hell proper to be given a substantive speaking role. Francesca's testimony and condemnation is the first historical record of her, laying the foundation for her remembrance and legacy.[5] Dante's knowledge of Francesca most likely stemmed from her nephew, Guido Novello da Polenta, who served as Dante's host in Ravenna at the end of his life.[6]

In Inferno 5, Dante and Virgil meet Francesca and her lover Paolo in the second circle of hell, reserved for the lustful. The couple are buffeted by violent winds in a similar manner that they allowed themselves to be swept away by their passions. Dante approaches Francesca and Paolo. Francesca takes ownership of telling their story while Paolo weeps in the background. She first introduces herself not by name, but by the city in which she was born; Francesca's self-association with the land implies a voluntary detachment from her personhood and a self-objectification.[citation needed]

Dante's condemnation of Francesca stems from her complete refusal of agency. In her compelling speech to Dante, Francesca blames love as the agent of her sin. Francesca explaining that Paolo loved her first and describes how "Love, which is swiftly kindled in the noble heart, seized this one for the lovely person that was taken from me; and the manner still injures me."[7] She depicts herself as a passive agent who succumbed to Paolo's love for her. Francesca's description of love "seizing" her implies that she views herself as a helpless victim of her circumstance. She continues that, "Love, which pardons no one loved from loving in return, seized me for his beauty so strongly that, as you see, it still does not abandon me."[8] Here, she affirms that her reciprocation of Paolo's affection was dictated by "Love" itself, rather than a genuine love that came from within. Again, she portrays herself as a passive victim, refusing to recognize her own agency. Finally, Francesca explains that "Love led us on to one death."[9] Francesca does not accept responsibility for the origins nor the consequences of her affair.

It is also important to underscore that Francesca and Paolo's adultery was enabled by literature. Francesca and Paolo's relationship began innocently while reading a tale about Lancelot du Lac. Francesca tells Dante that she "was kissed by so great a lover, he, who will never be separated from me, kissed my mouth, all trembling. Galeotto was the book and he who wrote it: that day we read there no further."[10] Again, Francesca refers to herself as a passive object and assigns agency to literature that she reads. Ironically, if Paolo and Francesca had finished reading, they would have learned that Guinivere and Lancelot's adultery eventually destroys King Arthur's kingdom.

Dante's literary portrayal of Francesca allows her to become a relevant example for moral agency. Dante portrays Francesca compassionately and assigns her a commanding and persuasive voice. Francesca is "never actively interrupted by any authoritative male voice, be it the pilgrim's, the narrator's or, importantly, her lover's, who is silently present at the scene of the testimony."[11] Additionally, Francesca's persuasive power derives from her language, which echoes that of love poetry, especially from Dante's early poems. In this way, Francesca becomes a reflection of Dante himself. At the end of Francesca's testimony, Dante faints and "fell as a dead body falls."[12] The pilgrim's symbolic death parallels Francesca's submission to her desires. Francesca becomes an "avatar of a persona that had been Dante's own."[13] Learning from Francesca's faults allows the pilgrim to rectify his own relationship with literature. Though Dante condemns Francesca, his compassionate literary portrayal gives her a dignity and a historical significance that she was deprived of in real life. In other words, her historical legacy transcends her literary condemnation.

- Works of art inspired by the Inferno scene

-

Henry Fuseli: Dante Observing the Soaring Souls of Paolo and Francesca, pen and ink, c. 1800

-

Joseph Anton Koch: Dante and Virgil in the Second Circle in Hell, pen, ink and watercolor on paper, 1823

-

Giuseppe Fraschieri: Dante e Virgilio incontrano Paolo e Francesca, oil on canvas, 1846 (Civica Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Savona)

-

Joseph Noel Paton: Dante Meditating the Episode of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, oil on canvas, 1852 (Bury Art Museum)

-

Gustave Doré: The Souls of Paolo and Francesca, wood-engraving, 1857

-

Gustave Doré: The Souls of Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1863

-

George Frederic Watts: Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1875 (Watts Gallery, Surrey)

-

Mosè Bianchi: Paolo and Francesca, watercolor and gold on paper, c. 1877 (Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan)

-

Henri-Jean Guillaume Martin: Paolo Malatesta et Francesca da Rimini aux enfers, oil on canvas, 1883 (Musée des beaux-arts, Carcassonne)

-

Auguste Rodin: Group Francesca de Rimini c. 1897

-

Auguste Rodin: Paolo et Francesca, or Couple damné (Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon)

-

Eugène Deully: Dante et Virgile aux Enfers, 1897

-

Amelia Bauerle: Paolo and Francesca, 1902

-

Umberto Boccioni: Il sogno, or Paolo e Francesca, oil on canvas, 1909 (Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna, Ferrara)

-

Gaetano Previati: Paolo e Francesca, oil on canvas, 1909

-

John Riley Wilmer: Paolo and Francesca, watercolor, gouache and ink, 1930

Reception and legacy

[edit]Giovanni Boccaccio

[edit]In the years following Dante's portrayal of Francesca, legends about Francesca began to appear. Chief among them was one put forth by poet Giovanni Boccaccio in his commentary on the Divine Comedy, Esposizioni sopra la Comedia di Dante. Boccaccio stated that Francesca had been tricked into marrying Giovanni through the use of Paolo as a proxy. Guido, fearing that Francesca would never agree to marry the crippled Giovanni, had supposedly sent for the much more handsome Paolo in Giovanni's stead. It wasn't until the morning after the wedding that Francesca discovered the deception. This version of events, however, is very likely a fabrication. It would have been nearly impossible for Francesca not to know who both Giovanni and Paolo were, and that Paolo was already married, given the dealings the brothers had had with Ravenna and Francesca's family. Also, Boccaccio was born in 1313, some 27 years after Francesca's death, and while many Dante commentators after Boccaccio echoed his version of events, none before him had mentioned anything similar.[14]

Modern reception

[edit]In the 19th century, the story of Paolo and Francesca inspired numerous theatrical, operatic, and symphonic adaptations.

In 2023, the musician Hozier released the single "Francesca" as part of his 2023 album Unreal Unearth.

Related works

[edit]

Poetry

[edit]- Leigh Hunt, The Story of Rimini (1816)

Theatre and opera

[edit]- Silvio Pellico, Francesca da Rimini, tragedy (1818)

- Feliciano Strepponi, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Padua 1823)

- Luigi Carlini, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Naples 1825)

- Saverio Mercadante, Francesca da Rimini, opera (Madrid 1831)

- Pietro Generali, Francesca da Rimini, opera, libretto by Paolo Pola (Venice 1828)

- Gaetano Quilici, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Lucca 1829)

- Giuseppe Staffa, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Naples 1831)

- Giuseppe Fournier-Gorre, Francesca da Rimini, opera in two acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Livorno 1832)

- Giuseppe Tamburini, Francesca da Rimini, opera in three acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Rimini 1835)

- Francesco Morlacchi, Francesca da Rimini, opera (composed for Venice 1836, but unperformed)

- Emanuele Borgatta, Francesca da Rimini, opera in three acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Genoa 1837)

- Gioacchino Maglioni, Francesca da Rimini, opera (Genoa 1840)

- Eugen Nordal (pseudonym of Johann Arnold-Gruber), Francesca da Rimini, opera after Paolo Pola (Linz 1840; performed posthumously)

- Salvatore Papparlado, Francesca da Rimini, opera in four acts (Genoa 1840; unperformed)

- Francesco Cannetti, Francesca da Rimini, opera, libretto by Felice Romani (Vicenza 1843)

- Vincenzo Sassaroli, Francesca da Rimini, opera, libretto by Felice Romani (Catania 1846)

- George Henry Boker, Francesca da Rimini, play (1853)

- Giovanni Franchini, Francesca da Rimini, opera in three acts, libretto by Felice Romani (Lisbon 1857)

- Jan Neruda, Francesca di Rimini, play (1860)

- Giuseppe Marcarini, Francesca da Rimini, opera, libretto by Benvenuti (Piacenza 1870)

- Hermann Goetz, Francesca von Rimini, opera in three acts, libretto by the composer (Mannheim 1877; overture and act III completed by Ernst Frank)

- Antonio Cagnoni, Francesca da Rimini, opera in four acts, libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni (Turin 1878)

- Gabriele D'Annunzio, Francesca da Rimini, tragedy (1901; written for D'Annunzio's mistress, Eleonora Duse)

- Ambroise Thomas, Françoise de Rimini, opera (Paris 1882)

- Antonio Scontrino, Francesca da Rimini, "tragedia" (in fact an opera) in five acts, libretto after D'Annunzio (Rome 1901)

- Stephen Phillips, Paolo and Francesca, play (1902)[15]

- Francis Marion Crawford, Francesca da Rimini, play in five acts (1902)

- Marcel Schwob, Francesca da Rimini, play, translation of Crawford (given with music by Gabriel Pierné Paris 1902, Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt)

- Eduard Nápravník, Francesca da Rimini, opera in four acts (St. Petersburg 1902)

- Sergei Rachmaninoff, Francesca da Rimini, opera in one act (two tableaux) with a prologue and an epilogue, libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky (Moscow 1906)

- Luigi Mancinelli, Paolo e Francesca, opera in one act (1907)[16]

- Emil Ábrányi, Paolo és Francesca, opera in three acts, libretto after Dante by Emil Ábrányi Sr. (Budapest 1912)

- Franco Leoni, Francesca da Rimini, opera in three tableaux, based on Crawford's play (Paris 1914, Opéra-Comique)

- Primo Riccitelli, Francesca da Rimini, opera

- Riccardo Zandonai, Francesca da Rimini, opera in four acts, libretto by Tito Ricordi, based on D'Annunzio (Turin 1914)

- Nino Berrini, Francesca da Rimini, play (1924)

Music

[edit]- Gioachino Rossini, "Farò come colui che piange e dice", aria (musical setting of Inferno, Canto 5, lines 126ff., 1848)

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Francesca da Rimini, symphonic poem (1876)

- Arthur Foote, Symphonic Prologue Francesca da Rimini, Op. 24 (1890)

- Antonio Bazzini, Francesca da Rimini, Symphonic Poem, Op. 77 (Berlin 1890)

- Pierre Maurice, Francesca da Rimini, Symphonic Poem, Op. 6 (1899)

- Paul von Klenau, Francesca da Rimini, Symphonic Poem (1913, revised 1919)

- Olga Gorelli, Paolo e Francesca, guitar duo from the album Hausmusik. 20th Century Chamber Music for the Home (2000)

- Mediæval Bæbes, "The Circle of the Lustful" from The Rose album (2002)

- Andrew Hozier-Byrne, "Francesca" from Unreal Unearth album (2023)

Film

[edit]- Paolo e Francesca, 1950 film by Raffaello Matarazzo

Art

[edit]- Joseph Anton Koch, Paolo and Francesca Surprised by Gianciotto, watercolor (1805; Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen)

- Marie-Philippe Coupin de la Couperie, The Tragic Love of Francesca da Rimini, oil on canvas (1812; Napoleonmuseum, Arenberg)

- Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas (1819;Musée des Beaux-Arts, Angers, France)

- Ary Scheffer, Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta Appraised by Dante and Virgil, oil on canvas (1835; Wallace Collection, London; an 1855 version is in the Louvre, Paris), and there are other versions

- Gustave Doré, Francesca da Rimini, several illustrations to Dante's Inferno (1857)

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini (1862)

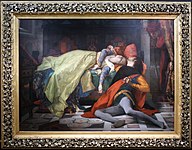

- Alexandre Cabanel, The Death of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, oil on canvas (1870; Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

- George Frederic Watts, Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas (between 1872 and 1884; private collection)

- Auguste Rodin, The Kiss, marble sculpture (1888; Musée Rodin, Paris)

- The tête-à-tête

-

William Dyce: Francesca da Rimini, oil on canvas, 1837 (Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh)

-

Anselm Feuerbach: Paolo und Francesca, study, 1864 (Kunsthalle Mannheim)

-

Anselm Feuerbach: Paolo und Francesca, sketch, 1864

-

Anselm Feuerbach: Paolo und Francesca, oil on canvas, 1864 (Schackgalerie, Munich)

-

Amos Cassioli: Paolo e Francesca or Il Bacio, 1870

-

Charles Edward Hallé: Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas

-

Ludwik Wiesiołowski: Francesca i Paolo, oil on canvas, 1885

-

Arnold Böcklin: Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1893 (Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur)

-

Frank Dicksee: Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1894

- The dagger scene and the lovers' death

-

Joseph Anton Koch: Paolo da Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini surprised by Gianciotto Malatesta, pen, ink and watercolor on paper, 1805 (Thorvaldsen Museum)

-

Bartolomeo Pinelli: La Franceschina di Rimini, c. 1809 (Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen)

-

Marie-Philippe Coupin de la Couperie: The Tragic Love of Francesca da Rimini, 1812 (Napoleonmuseum, Arenenberg, Constance)

-

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres: Gianciotto Discovers Paolo and Francesca, oil on canvas, 1819 (Musée Bonnat, Bayonne)

-

Eugène Delacroix: Paolo et Francesca, watercolor, 1825

-

Gustave Doré: Illustration of Inferno, Canto 5 (lines 134–135), 1857

-

Francisco Díaz Carreño: Francisca de Rímini, oil on canvas, 1866 (Prado, Madrid)

-

Gaetano Previati: Paolo e Francesca, or Morte di Paolo e Francesca, oil on canvas, c. 1887 (Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti di Bergamo)

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Italian pronunciation: [franˈtʃeska da (r)ˈriːmini]; Italian pronunciation: [franˈtʃeska da (p)poˈlɛnta] [17][18]

References

[edit]- ^ Antonio Enzo Quaglio, Matilde Luberti (1970). Francesca da Rimini (in Italian). Enciclopedia Dantesca. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved December 2022.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (2003). The Divine Comedy. New York: New American Library. p. 52. Translation and commentary by John Ciardi.

- ^ Alighieri, Dante (2000). The Inferno. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 106–107. Translation and commentary by Robert and Jean Hollander.

- ^ Barolini, Teodolinda (January 2000). "Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender". Speculum. 75 (1): 3. doi:10.2307/2887423. JSTOR 2887423. S2CID 161686492.

- ^ Barolini, Teodolinda. 2000. "Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, romance, gender". Speculum (Cambridge, Mass.). 1-28.

- ^ Dante Alighieri, Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez, and Robert Turner. 1996. The divine comedy of Dante Alighieri. Volume 1, Volume 1. Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Dante Alighieri, Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez, and Robert Turner. 1996. The divine comedy of Dante Alighieri. Volume 1, Volume 1. Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Dante Alighieri, Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez, and Robert Turner. 1996. The divine comedy of Dante Alighieri. Volume 1, Volume 1. Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Dante Alighieri, Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez, and Robert Turner. 1996. The divine comedy of Dante Alighieri. Volume 1, Volume 1. Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Dante Alighieri, Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez, and Robert Turner. 1996. The divine comedy of Dante Alighieri. Volume 1, Volume 1. Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ John Freccero. "The Portrait of Francesca. Inferno V." MLN 124, no. 5S (2009): 7–38. doi:10.1353/mln.0.0224.

- ^ Dante Alighieri, Robert M. Durling, Ronald L. Martinez, and Robert Turner. 1996. The divine comedy of Dante Alighieri. Volume 1, Volume 1. Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Barolini, Teodolinda. 2000. "Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, romance, gender". Speculum (Cambridge, Mass.). 1-28.

- ^ Barolini, Teodolinda (January 2000). "Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender". Speculum. 75 (1): 16. doi:10.2307/2887423. JSTOR 2887423. S2CID 161686492.

- ^ Produced by Sir George Alexander at the St James's Theatre beginning 6 March 1902. Mason, p. 237. See William Calin, "Dante on the Edwardian Stage: Stephen Phillips's Paolo and Francesca." In: Medievalism in the Modern World. Essays in Honour of Leslie J. Workman, ed. Richard Utz and Tom Shippey (Turnhout: Brepols, 1998), pp. 255–61.

- ^ Paolo e Francesca, opera by Luigi Mancinelli, booklet (synopsis, libretto), 2004 recording Naxos Records

- ^ Luciano Canepari. "Francesca". DiPI Online (in Italian). Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Luciano Canepari. "Polenta". DiPI Online (in Italian). Retrieved 11 January 2021.

General references

[edit]- Mason, A. E. W. (1935). Sir George Alexander & The St. James' Theatre. Reissued 1969, New York: Benjamin Blom.

- Hollander, Robert and Jean (2000). The Inferno. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-49698-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Singleton, Charles S. (1970). The Divine Comedy, Inferno/Commentary. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01895-2.

External links

[edit]- World of Dante, multimedia website that includes gallery of images of the Paolo and Francesca episode

- WisdomPortal, includes images of related artworks

- The Story of Rimini, Google Books edition of Leigh Hunt's poem

- Website of the Giornate Internazionali Francesca da Rimini at the Centro Internazionale di Studi Francesca da Rimini, Los Angeles (including one more image gallery)