Richard Goldstone

Richard J. Goldstone | |

|---|---|

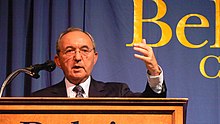

Goldstone in 2019 | |

| Born | 26 October 1938 |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for | Chairing the Goldstone Commission, prosecuting war crimes in Yugoslavia and Rwanda, leading the United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict |

| Spouse | Noleen Goldstone |

| Children | 2 |

Richard Joseph Goldstone (born 26 October 1938) is a South African retired judge who served in the Constitutional Court of South Africa from July 1994 to October 2003. He joined the bench as a judge of the Supreme Court of South Africa, first in the Transvaal Provincial Division from 1980 to 1989 and then in the Appellate Division from 1990 to 1994. Before that, he was a commercial lawyer in Johannesburg, where he entered legal practice in 1963 and took silk in 1976.

He is considered to be one of several liberal judges who issued key rulings that undermined apartheid from within the system by tempering the worst effects of the country's racial laws. Among other important rulings, Goldstone made the Group Areas Act – under which non-whites were banned from living in "whites only" areas – virtually unworkable by restricting evictions. As a result, prosecutions under the act virtually ceased.

During the transition from apartheid to multiracial democracy in the early 1990s, he headed the influential Goldstone Commission investigations into political violence in South Africa between 1991 and 1994. Goldstone's work enabled multi-party negotiations to remain on course despite repeated outbreaks of violence, and his willingness to criticise all sides led to him being dubbed "perhaps the most trusted man, certainly the most trusted member of the white establishment" in South Africa.[1] He was credited with playing an indispensable role in the transition and became a well known public figure in South Africa, attracting widespread international support and interest.

Goldstone's work investigating violence led directly to his being nominated to serve as the first chief prosecutor of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda from August 1994 to September 1996.[2] He prosecuted a number of key war crimes suspects, notably the Bosnian Serb political and military leaders, Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić. On his return to South Africa he took up a seat on the newly established Constitutional Court of South Africa, to which he had been nominated by President Nelson Mandela.[2]

In 2009, Goldstone led a fact-finding mission created by the UN Human Rights Council to investigate international human rights and humanitarian law violations related to the Gaza War.[2][3] The mission concluded that Israel and Hamas had both potentially committed war crimes and crimes against humanity, findings which sparked outrage in Israel and the initiation of a personal campaign against Goldstone.[4] In 2011, in the light of investigations by the Israeli forces which indicated that they had not intentionally targeted civilians as a matter of policy, Goldstone wrote that if evidence which had been available later had been available at the time, the Goldstone Report would have been a different document.[5]

Early life and education

Goldstone was born on 26 October 1938 in Boksburg near Johannesburg in South Africa's Transvaal Province.[6] His parents were second-generation immigrants:[7] his maternal grandfather was English and his paternal grandfather was a Lithuanian Jew who emigrated in the 19th century.[8] He was educated at the King Edward VII School in Johannesburg and read law at the University of the Witwatersrand, graduating in 1962 with a BA LLB cum laude.[9][2] He later recalled: "My grandfather decided when I was about four [that] I was going to be a barrister, so I just always assumed I was. It turned out to be a wise decision."[10]

At university, he became involved in anti-apartheid activism, inspired partly by his parents' opposition to racial discrimination.[10][11] As chairman of the university's student representative council and president of the National Union of South African Students, he campaigned against the exclusion of black students.[12][13] He also attracted attention from the state security police by having contact with banned anti-apartheid groups, including the African National Congress.[14]

Early legal career

After his graduation, Goldstone was admitted to the Johannesburg Bar in 1963. He practised corporate and intellectual property law as a barrister in Johannesburg for 17 years, establishing a practice that was "100 percent commercial".[15][16] He was appointed as Senior Counsel in 1976.[17]

Supreme Court of South Africa: 1980–1994

In 1980, Goldstone was appointed as a judge of the Transvaal Provincial Division of the Supreme Court of South Africa.[2] At the time of his appointment he was the youngest Supreme Court judge in the country.[18] He served in the Supreme Court for 14 years, gaining promotion to the Appellate Division in 1989.[6]

Jurisprudence

Goldstone later said that his nomination to the bench created a "moral dilemma", insofar as South African judges were expected to uphold apartheid legislation, but that, "the approach was that it was better to fight from inside than not at all".[19] On these grounds, he was apparently urged by several anti-apartheid lawyers to accept the appointment.[13]

He noted in 1992 that most South African judges "applied such [apartheid] laws without commenting upon their moral turpitude." A number, including Goldstone, were more outspoken – a policy that he felt aided the credibility of the courts. There was a fine dividing line between applying moral standards and promoting political doctrines, but Goldstone believed that "in my view, if a judge is to err, it should be on the side of defending morality."[20] He took the view that "judges have a duty to act morally, and if they're dealing with laws which have an unjust effect, I think it's their duty – if they can, within the powers they've got legitimately – to interpret the laws and give judgments which will make them less harsh and less unjust."[1] Being a judge in apartheid-era South Africa was a challenge, but it had its rewards; "I hated in the morning the thought of having to do this for another day, [but] by the end of the day, I was exhilarated at the reaction and how important the work was."[21]

Goldstone's career as a judge was characterised by bold acts of judicial activism that soon attracted national and international interest.[13] He was described as "an outstanding commercial lawyer who had shrewdly and inventively applied the law to secure justice in politically controversial and human rights cases."[11] Employing the bench as a means of making ordinary South Africans aware of the iniquities of apartheid, he gained a reputation as a committed, compassionate, legally meticulous and politically astute jurist who championed international human rights and sought to temper the effects of South Africa's apartheid laws.[1][7] He sought to retain his independence, refusing to kowtow to the authorities.[14] As Reinhard Zimmermann puts it, Goldstone "emerged as one of the leading 'liberal' judges who never showed any propensity towards the then prevailing executive-mindedness".[22]

His judicial approach was influenced by the fact that although the ruling National Party had built up a framework of racist and unequal laws aimed at repressing the rights of non-whites, the country had retained the underlying structure and principles of Anglo-Dutch common law. According to Davis & Le Roux (2009), a group of liberal judges that included Goldstone, Gerald Friedman, Ray Leon, Johann Kriegler, John Milne and Lourens Ackermann sought to read the apartheid legislation "as narrowly as possible to give effect to the values of the common law".[23]

This philosophy led Goldstone to issue rulings that undermined key aspects of the apartheid system. One of his most significant rulings concerned the Group Areas Act that mandated the eviction of non-whites from areas reserved for whites. His ruling in the case of S v Govender in 1982 that evictions of non-whites were not automatically required by the Act led to the virtual cessation of such evictions.[7] Following the judgement it became so difficult to evict non-whites from whites-only areas that the system of housing segregation began to break down.[24] Prosecutions under the Act fell from 893 between 1978–1981 to only one in 1983.[25] Geoffrey Budlender, former director of the anti-apartheid Legal Resources Centre, commented of Goldstone's decision in the Govender case that "it was an alert judge trying to apply human rights standards to a repressive piece of legislation. And it was Goldstone's work; it wasn't our work that stopped the Group Areas prosecutions in the end." Budlender noted that "it was a matter of great debate in the eighties about whether decent people should accept appointments to the bench, because they were enforcing repressive laws," but stated that "[f]rom the point of view of the practitioner trying to run human rights cases and public-interest cases, we prayed for a Goldstone or a [John] Didcott on the bench. That was our dream."[26]

In 1985, Goldstone ruled that the government's mass sacking of 1,700 black staff at Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto had been illegal.[27] The following year, he was the first judge to free a political prisoner who had been detained under a recently imposed state of emergency under which the government had given itself draconian police powers.[28] Another important ruling against the state in 1988 resulted in the release of a detainee who had not been advised by the police that he was entitled to a lawyer.[1] In 1989, Goldstone became the first South African judge under apartheid to take on a black law clerk, an African-American Yale Law student named Vernon Grigg.[29] Goldstone also used his judicial prerogatives to visit thousands of people who had been imprisoned without trial, including some who later became members of the post-apartheid South African government.[10] Although he could do little to free them, his visits served to reassure the prisoners – and serve notice to the prison administration – that someone in a position of power was taking an active interest in their well-being. Few white judges at the time enjoyed the trust and respect of the black majority; Goldstone became a notable exception.[30]

Some of South Africa's laws and emergency regulations mandated particular penalties which judges had no discretion to modify. South Africa's whites-only parliament pursued a doctrine of parliamentary supremacy, passing laws which judges were absolutely bound to enforce if they had been enacted by parliament or were faithful to what parliament had done.[31] Goldstone distressed civil rights lawyers in 1986 when he concurred without comment with a decision that allowed the jailing of a 13-year-old boy for disrupting school. Goldstone later remarked that he was constrained by the law, that "the emergency regulations covered the situation."[1] The laws and regulations also included the death penalty for certain crimes such as murders committed without any extenuating circumstances; although Goldstone was personally opposed to the death penalty, he was nonetheless required to pass death sentences on two convicted murderers.[32] His reluctance to impose death penalties prompted criticism from judges who were in favour of capital punishment. Another Transvaal Supreme Court judge, D. Curlewis, commented in 1991 that "a person who deserves to hang was more likely to get the death sentence from me or my ilk" than Goldstone or other liberal judges, who were "at heart abolitionists for one reason or another... Obviously, and for that reason, they cannot be sound on the imposition of the death penalty."[33] During his career as judge, Goldstone sentenced to death 2 black South Africans and was involved in upholding the death sentences of over 20 other black South Africans.[34][35]

Albie Sachs, who was later to serve alongside Goldstone on the Constitutional Court of South Africa, commented that Goldstone's judicial career demonstrated "that an honest and dignified judge who's sensitive to fundamental human rights of all human beings, even in the most dire circumstances, could find some space for concepts of legality and respect for human dignity."[36]

Sebokeng Inquiry and Goldstone Commission

In 1990, President F. W. de Klerk began the negotiation process that was to lead to the end of apartheid in 1994. At the time, South Africa was plagued by regular massacres as members of the African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) fought for dominance. The police and security forces often reacted to demonstrations with indiscriminate force, and the ANC claimed that a hypothesised "Third Force" was engaged in covert destabilisation. The violence caused serious problems in building trust between the parties.

The negotiations broke down soon after they started due to a mass shooting at Sebokeng township near Johannesburg in March 1990, in which 281 demonstrators were shot and 11 killed by South African police. After pressure from the ANC, de Klerk appointed Goldstone to investigate the incident. His report was published in September 1990 and was described at the time as "one of the strongest indictments of South Africa's police ever made by a government-appointed investigator."[37] He condemned the police for a breakdown in discipline and recommended that a number of individual police officers be prosecuted.[38] Nine policemen were subsequently charged with murder.[39]

To aid the transition to multiracial democracy, the South African government established a Commission of Inquiry Regarding the Prevention of Public Violence and Intimidation in October 1991 to investigate human rights abuses committed by the country's various political factions. Its members were chosen by consensus among the three main parties.[40] Goldstone had by now become reputed as an impartial and unimpeachable judge, and was asked by ANC chairman Nelson Mandela to head the commission; it became known as the Goldstone Commission.[7] Goldstone explained later that he had been selected because he had earned the confidence of both sides: "The government was aware that I would not make findings against it without good cause, and the majority of South Africans had confidence that I would quote hesitate to make findings against the government if the evidence justified it."[41] He nonetheless received numerous death threats.[10] He continued to work as an appeals court judge throughout his time chairing the commission, hearing cases during the mornings and afternoons and then continuing through to midnight on Commission business.[15]

The Commission sat for three years, carrying out 503 investigations that triggered the initiation of 16 prosecutions.[30] It had no judicial powers and could not issue binding regulations but had to establish its legitimacy through its reports and recommendations. It soon gained a reputation for even handedness, criticising all sides in often trenchant terms. The rivalry between the ANC and IFP was blamed for being "the primary cause" of violence and Goldstone urged both sides to "abandon violence and intimidation as political weapons". The government's security forces were found to have been involved in numerous abuses of human rights, though Goldstone rejected Nelson Mandela's claims that President de Klerk was personally involved and described such suggestions as "unwise, unfair and dangerous".[39] One of Goldstone's most important findings was the revelation in November 1992 that a secret military intelligence unit of the South African Defence Force was working to sabotage the ANC while posing as a legitimate business corporation. The ensuing scandal led to De Klerk purging the army and intelligence services.[30]

Goldstone's findings attracted praise and criticism from all sides.[39] Some anti-apartheid activists criticised Goldstone for what they saw as balancing his reports by apportioning blame equally; Goldstone responded that his findings reflected the fact that all sides had "dirty hands".[1] Nonetheless, his impartiality and willingness to speak out led to him becoming, as the Christian Science Monitor put it in 1993, "arguably the most indispensable arbitrator in South Africa's turbulent transition to democracy." He became a household name and was voted the top newsmaker of 1992 in a South African poll, well ahead of either de Klerk or Mandela.[42] His character was cited by other lawyers as a key asset in making the commission a success; one lawyer commented, "He has the rare ability to straddle both the legal and political worlds. He is a great strategist and combines a deep humanity with a political sensitivity."[10]

As well as reporting on political violence, Goldstone proposed practical measures to end the violence in venues such as commuter trains, taxis, mines, township hostels and the troubled Natal region. He also succeeded in persuading the government to accept an international rôle in the transition – which it had previously strongly opposed – as well as forcing it to undertake a major restructuring of the security forces and purging subversive elements in the military.[42] According to Goldstone, the commission's work helped to calm South Africa during the transition period. He regarded it as "a vitally important safety valve" that provided a "credible public instrument" to deal with incidents that might otherwise have derailed the negotiations.[10] The international community took a similar view; his work was supported and funded by the UN, the Commonwealth and the European Community, who regarded it as vital to expose the truth behind political violence in order to achieve democratic stability.[15]

Goldstone's work was to pave the way for the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1995, a body that he strongly supported. Its chairman, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, commented that Goldstone had made an "indispensable" contribution to the peaceful democratic transition in South Africa.[36] The commission's final report was strongly critical of the apartheid-era legal system but commended the role of a few judges, including Goldstone, who "exercised their judicial discretion in favour of justice and liberty wherever proper and possible". It noted that although they were few in number, such figures were "influential enough to be part of the reason why the ideal of a constitutional democracy as the favoured form of government for a future South Africa continued to burn brightly throughout the darkness of the apartheid era." The Commission found that "the alleviation of suffering achieved by such lawyers substantially outweighed the admitted harm done by their participation in the system."[43] Reinhard Zimmermann commented in 1995 that "Goldstone's reputation as a sound and impeccably impartial lawyer coupled with his genuine concern for social justice have invested him, across the political spectrum, with a degree of legitimacy that is probably unequalled in South Africa today."[22]

Constitutional Court of South Africa: 1994–2003

From July 1994 to October 2003, Goldstone was a judge in the Constitutional Court of South Africa, which was newly established under the post-apartheid Interim Constitution.[6] Justice Albie Sachs described Goldstone as representing "a sense of continuity" between the traditions of the past that managed to survive the years of apartheid, and the whole new era of the constitution that governs South Africa today.[36] Notable judgments written by Goldstone included three important decisions on unfair discrimination and the right to equality: President v Hugo, Harksen v Lane, and J v Director-General, Home Affairs.

International service

Chief UN Prosecutor in Yugoslavia and Rwanda

In August 1994, Goldstone was named as the first chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), which was established by a resolution of the UN Security Council in 1993. When the Security Council established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in late 1994, he became its chief prosecutor, too. His appointment to the tribunals came as something of a surprise, even to Goldstone himself, as he had only limited experience of international law and Yugoslavian affairs and had never been a prosecutor before.[10] He owed his appointment to the Italian chief judge of the ICTY, Antonio Cassese. There had been lengthy wrangling between UN member states about whom to appoint as a prosecutor and none of the candidates proposed so far had been accepted.[44] The French national counsel, Roger Errera, suggested Goldstone, commenting that "if he is Jewish, that goes down well. Everyone suspects everyone in the former Yugoslavia. So it's better that he is neither Catholic, nor Orthodox, nor Muslim."[44]

Goldstone was approached by Cassese and expressed an interest in the position. President Mandela supported his wish to take up the position at The Hague, as Goldstone later recalled: "He certainly encouraged me. He thought it was important to take what was the first offer of a major international position after South Africa ceased to be a pariah."[20] However, the offer put Mandela in a difficult spot. He wanted Goldstone, who was one of the few South African jurists to have earned the respect of both blacks and whites, for South Africa's newly established Constitutional Court. Mandela struck a deal with the UN Secretary-General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, that Goldstone would serve only half of his four-year term as prosecutor and would then return to take up his post in South Africa.[45] The president rushed through a constitutional amendment that would allow Goldstone to be named, take an immediate period of leave to serve at the tribunal and then return to his spot on the Constitutional Court.[21] He proved to be an ideal candidate, as he had been suggested by the French, was not too hot-headed for the British, was strong enough to satisfy the Americans and his credentials as a white South African who had opposed apartheid satisfied the Russians and Chinese. The UN Security Council unanimously approved his appointment to the rôle of prosecutor.[44]

In his roles at the ICTY and ICTR he had to design prosecutorial strategies for both those ground-breaking tribunals, from scratch. In doing so, he sought to be scrupulously even-handed – a goal he was more easily able to achieve at ICTY than at ICTR. He built his strategy at both courts to a large degree on that pursued by the prosecutors at the Nuremberg Tribunal of 1945–46. He served as the chief prosecutor of the two tribunals until September 1996.[2] Among his most notable legal achievements as chief prosecutor was securing the recognition of rape as a war crime under the Geneva Convention.[46]

Goldstone was hindered by the inflexible bureaucracy of the UN, finding the newly established ICTY in a shambles when he joined the tribunal.[20] The tribunal lacked political legitimacy, financial support and prosecutorial direction; its failure to even bring any prosecutions had led to it being criticised by the media as "a fig leaf for inaction", and Goldstone was asked by the former British prime minister Edward Heath: "Why did you accept such a ridiculous job?"[21] He had to make repeated appeals to the UN's hierarchy and to donor nations for the equipment and funding that the tribunal needed to operate.[20] He quickly found that the key to the job was to take "[the] big-picture diplomatic role and [recognise] that the hands-on prosecution work could be pushed down to experienced prosecutors and investigators like [Graham] Blewitt – at least for the time being."[47] He undertook a flurry of media appearances and financial negotiations that led to the tribunal being properly staffed for the first time, with many staff being recruited through his own personal networks; a budget of eight million dollars from thirteen countries, supplemented by a $300,000 donation from George Soros; and the first indictment, of Bosnian Serb prison camp guard Duško Tadić.[48]

Another problem Goldstone faced was the reluctance of NATO peacekeeping forces in Bosnia to apprehend war crimes suspects. He was bitterly critical of what he called the "highly inappropriate and pusillanimous policy" of Western countries in declining to pursue suspected war criminals, singling out France and the United Kingdom as particular culprits. By the end of his time as prosecutor he had issued 74 indictments but only seven of the accused had been apprehended.[49]

Goldstone was instrumental in preventing the Dayton Agreement of December 1995 including amnesty provisions for those accused of war crimes in the former Yugoslavia. Some commentators had advocated including an amnesty as the price for peace; Goldstone was resolutely opposed to this, not only because it would enable those responsible for atrocities to escape justice but also because of the dangerous precedent it could set, where powerful actors such as the United States could bargain away the ICTY's mandate for political convenience. In response, Goldstone pushed through a new indictment of the Bosnian Serb president Radovan Karadžić and his army chief Ratko Mladić for the Srebrenica massacre, which was issued two weeks into the peace talks at Dayton.[50] He lobbied President Bill Clinton to resist any such demands and made it clear that an amnesty would not be a legal basis for the ICTY to suspend indictments. In the end, no amnesty was included in the Dayton Agreement.[30][51] Goldstone's actions were later credited with making the negotiations a success. The chief US negotiator, Richard Holbrooke, described the tribunal as "a huge valuable tool" which had enabled Karadžić and Mladić to be excluded from the talks, with the Serbian side represented instead by the more conciliatory Milosević. The Dayton Agreement put direct responsibility on all sides to send suspects to The Hague, committing the Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian governments to cooperating with the ICTY in future.[52]

When he retired from the Office of the Prosecutor in 1996, Goldstone was replaced by the distinguished Canadian lawyer Louise Arbour. His contribution was praised by colleagues at the ICTY: "Goldstone was absolutely right for his time because he came with moral clout from South Africa and his own particular status as a champion of human rights."[53]

Argentina

He was a member of the International Panel of the Commission of Enquiry into the Activities of Nazism in Argentina (CEANA) which was established in 1997 to identify Nazi war criminals who had emigrated to Argentina, and transferred victim assets (Nazi gold) there.[54]

Kosovo

Goldstone was chair of the Independent International Commission on Kosovo from August 1999 until December 2001.[2]

Volcker Committee

In April 2004, he was appointed by Kofi Annan, the UN Secretary General, to the Independent Inquiry Committee, chaired by Paul Volcker, to investigate the Iraq Oil for Food program.[2]

The Goldstone Report

During the Gaza War between Israel and Hamas in December 2008 – January 2009, the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) passed a resolution condemning Israel for "grave violations" of human rights and calling for an independent international investigation. The UNHRC appointed a four-person team, headed by Goldstone,[56][57] to investigate "all violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law that might have been committed at any time in the context of the military operations that were conducted in Gaza during the period from 27 December 2008 and 18 January 2009, whether before, during or after."[58]

According to a Reuters report Goldstone said he had spent many days and "sleepless nights" deciding whether to accept the mandate, saying that it had come as "quite a shock". He continued, "I can approach the daunting task I have accepted in an even-handed and impartial manner and give it the same attention that I have to situations in my own country," where his experience had been that "transparent, public investigations are very important, important particularly for the victims because it brings acknowledgement of what happened to them."[57] He explained that he had long "taken a deep interest in Israel, in what happens in Israel, and I have been associated with organisations that have worked in Israel" and "decided to accept it because of my deep concern for peace in the Middle East, and my deep concern for victims in all sides in the Middle East."[59]

Goldstone insisted that he would not follow a one-sided mandate but would investigate any abuses committed by either side during the conflict.[60] He said that he had initially not been willing to take on the mission unless the mandate was expanded to cover all sides. Despite then-president of the Human Rights Council, Ambassador Martin Uhomoibhi's verbal commitment that there was no objection to the revised mandate,[61] the Human Rights Council never voted to revise the mandate, and resolution S-9/1 remained unchanged.[62]

The Israeli government refused to cooperate with the investigation, accusing the UN Human Rights Council of anti-Israel bias and arguing that the report could not possibly be fair.[63]

In a 20 January 2011 panel discussion at Stanford University, Goldstone said that the UNHRC "repeatedly rush to pass condemnatory resolutions in the face of alleged violations of human rights law by Israel but ... have failed to take similar action in the face of even more serious violations by other States. Until the Gaza Report they failed to condemn the firing of rockets and mortars at Israeli civilian centers."[64][65]

The report, released on 15 September 2009, concluded that both sides had committed violations of the laws of war. It stated that Israel had used disproportionate force, targeted Palestinian civilians, used them as human shields and destroyed civilian infrastructure. Hamas and other armed Palestinian groups were found to have deliberately targeted Israeli civilians and sought to spread terror in southern Israel by mounting indiscriminate rocket attacks. The report's conclusions were endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council.[63]

On 16 October 2009, UN Human Rights Council voted in support of the Goldstone Report where twenty-five member nations voted in favour of the resolution endorsing the report, six voted against endorsement while another eleven remained impartial. Goldstone has criticised the United Nations Human Rights Council's selective endorsement of the report his commission compiled, since the resolution adopted chastises Israel only, when the report itself is critical of both parties.[66]

The Israeli government and some Jewish groups strongly criticised the report, which they asserted was biased and commissioned by a UN body that was hostile to Israel. Hamas also dismissed the findings that it had committed war crimes. Goldstone himself came under sustained personal attack, with critics accusing him of bias, dishonesty and improper motives in being party to the report.[67] Goldstone denied the accusations, saying he felt that being a Jew increased his obligation to participate in the investigation.[63]

In a 1 April 2011 article in the Washington Post reflecting on the commission's work, Goldstone wrote that the report would have been different if he had been aware of information that had become known since its issuance. While expressing regret that Israel's failure to co-operate with the commission had hindered its ability to gather exculpatory facts, he approved Israel's subsequent internal investigations into incidents described in the report as well as their establishment of policies to better protect civilians in future conflicts. He contrasted the Israeli reaction with the failure of Hamas to investigate or modify their methods and procedures. Goldstone said he had hoped that the commission's inquiry "would begin a new era of evenhandedness at the U.N. Human Rights Council, whose history of bias against Israel cannot be doubted".[5] In addition, according to a report in Haaretz, Goldstone told associates in early 2011 that "he has been in great distress and under duress" ever since publication of his report.[68]

Academic and charity activities

Goldstone served as the founding national president of the National Institute of Crime Prevention and the Rehabilitation of Offenders (NICRO), a body established to look after prisoners who had been released; chairperson of the Bradlow Foundation, a charitable educational trust; and head of the board of the Human Rights Institute of South Africa (HURISA).[69] In March 1996, Goldstone was named chancellor of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.[70] He served for two terms, stepping down in September 2006.[71] In October 2003, Goldstone gave a lecture entitled "Preventing Deadly Conflict" at the University of San Diego's Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice Distinguished Lecture Series. He was a Global Visiting Professor of Law at New York University School of Law in spring 2004, and in the fall, he was the William Hughes Mulligan Visiting Professor at Fordham University School of Law. In spring 2005, he was the Henry Shattuck Visiting Professor Law at Harvard Law School.[72] Goldstone participated as guest faculty in the Oxford-George Washington International Human Rights Program in 2005.[73]

Goldstone was named the 2007 Weissberg Distinguished Professor of International Studies at Beloit College, in Beloit, Wisconsin. From 17 to 28 January 2007 he visited classes, worked with faculty and students, participated in panel discussions on human rights and transitional justice with leading figures in the field and delivered the annual Weissberg Lecture, "South Africa's Transition to Democracy: The Role of the Constitutional Court" on 24 January at the Moore Lounge in Pearsons Hall.[74] In Fall 2007 he was the William Hughes Mulligan Professor of International Law at Fordham University School of Law, and held that position again in Fall 2009. Fordham Law presented him with a Doctor of Laws, honoris causa, in 2007, the highest honor the school can bestow.[75] Goldstone also was the Woodrow Wilson Visiting Scholar in Political Science at Washington & Jefferson College in 2009.[76]

He also continues as a member of the board of directors of the Salzburg Global Seminar.[77] Goldstone serves as a trustee for Link-SA, a charity which funds the tertiary education of South Africans from impoverished backgrounds.

He is currently a member of the Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute's International Council.

Goldstone serves on the Board of Directors of several nonprofit organisations that promote justice, including Physicians for Human Rights, the International Center for Transitional Justice, the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, the South African Legal Services Foundation, the Brandeis University Center for Ethics, Justice, and Public Life, Human Rights Watch, and the Center for Economic and Social Rights.[78] Goldstone was president of the Jewish training and education charity World ORT between 1997 and 2004.[79] He was an honorary member of the Board of Governors of Hebrew University for over ten years prior to June 2010, when the university announced he had been dropped from the Board due to inactivity "for a decade or more".[80] In April 2010, Jerusalem lawyer David Schonberg had requested Goldstone be removed from the Board because of the UN report on Gaza. A university spokesperson stated that removing inactive members was a routine procedure, that other inactive members had also been removed, and that Goldstone's removal had "nothing to do with his Report about Gaza".[80][81][82]

Awards and honours

Goldstone has received the 1994 International Human Rights Award of the American Bar Association, the 2005 Thomas J. Dodd Prize in International Justice and Human Rights, and the 2009 MacArthur Award for International Justice, announced by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.[72][83]

He holds honorary degrees from Whittier College (2008),[84] Hebrew University, the University of Notre Dame, the University of Maryland, and the Universities of Cape Town, British Columbia, Glasgow, and Calgary among others.[72] He was the first person to be granted the title, "The Hague Peace Philosopher" in 2009, as part of the new Spinoza Fellowship of The Hague, the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS), Radio Netherlands, and The Hague Campus of Leiden University.[85] He is an honorary fellow of St John's College, Cambridge, an honorary member of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York,[86] a foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Goldstone was a fellow of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University in 1989.[72]

Personal life and religion

His family was non-religious,[87] but he credits his Jewishness with having shaped his ethical views through being part of a community that has been persecuted throughout history.[14] Goldstone has written about the role that those of Jewish heritage played in the fight against apartheid noting, subsequent to Nelson Mandela's death, that Mandela had himself observed "I have found Jews to be more broad-minded than most whites on issues of race and politics, perhaps because they themselves have historically been victims of prejudice."[88]

He is married to Noleen Goldstone. They have two daughters and four grandsons.

Publications

Books

- International judicial institutions : the architecture of international justice at home and abroad, co-authored with Adam M. Smith. London and New York: Routledge, 2009. ISBN 978-0-415-77645-5 (hardback); ISBN 978-0-415-77646-2 (paperback.)

- For humanity: reflections of a war crimes investigator. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-300-08205-0

- Do judges speak out?. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations, 1993. ISBN 978-0-86982-431-3

Lectures

- The Future of International Criminal Justice in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- The Developing Global Rule of Law in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

Contributions to edited volumes, and forewords to books by others

- Goldstone, Richard J. (1996). "From the Holocaust: Some Legal and Moral Implications". In Rosenbaum, Alan S. (ed.). Is the Holocaust Unique?: Perspectives on Comparative Genocide (3rd ed.). Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press (published 2008). ISBN 978-0-8133-4406-5.

- Goldstone, Richard (2005). "The Tension Between Combating Terrorism and Protecting Civil Liberties". In Wilson, Richard Ashby (ed.). Human Rights in the 'War on Terror'. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85319-4.

Goldstone has written forewords to books including Martha Minow's Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History after Genocide and Mass Violence (ISBN 978-0-8070-4507-7) and War Crimes: The Legacy of Nuremberg (ISBN 978-0-8133-4406-5), which examines the political and legal influence of the Nuremberg trials on contemporary war crime proceedings.

Goldstone, writing in The New York Times in October 2011, said that "in Israel, there is no apartheid. Nothing there comes close to the definition of apartheid under the 1998 Rome Statute."[89]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Keller, Bill (8 March 1993). "Cape Town Journal; In a Wary Land, the Judge Is Trusted (to a Point)". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Richard J. Goldstone Appointed to Lead Human Rights Council Fact-finding mission on Gaza Conflict". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 3 April 2009.

- ^ "UN appoints Gaza war-crimes team". BBC News. London. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ "Judge Goldstone to visit Israel, says minister". The Guardian. London. Associated Press. 5 April 2011.

- ^ a b Goldstone, Richard (1 April 2011). "Reconsidering the Goldstone Report on Israel and war crimes". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b c "Justice Richard Goldstone". Constitutional Court of South Africa. 20 June 2006. Archived from the original on 20 June 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d Devine, Carol; Hansen, Carol Rae; Wilde, Ralph & Poole, Hilary (1999). "Chapter 7: Human Rights Activists". Human Rights: The Essential Reference. Phoenix, Arizona: Oryx Press. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-1-57356-205-8. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ "Judge of our inactions". The Guardian. 1 October 1994.

- ^ The International Who's Who 2004. Europa Publications. 2003. p. 624. ISBN 978-1-85743-217-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shaw, John (2002). Washington diplomacy: profiles of people of world influence. Algora Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-87586-160-9.

- ^ a b Shimoni, Gideon (2004). "The Jewish Response to Apartheid: The Record and Its Consequences". In Mendelsohn, Ezra (ed.). Jews and the state: dangerous alliances and the perils of privilege. Oxford University Press US. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-19-517087-0.

- ^ Chaskalson, Arthur; Bizos, George (29 January – 5 February 2010). "Chaskalson and Bizos come out in defence of Richard Goldstone". SA Jewish Report. p. 16.

- ^ a b c Schabas, William A.; Goldstone, Richard J. (1 July 2001). "For Humanity: Reflections of a War Crimes Investigator". American Journal of International Law. 95 (3): 742–744. doi:10.2307/2668526. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2668526. S2CID 230912927.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c Raghavan, Sudarsan (14 March 1995). "Richard J. Goldstone – A South African jurist takes on Balkan and Rwanda conflicts, seeking to punish war criminals". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c Carlin, John (22 November 1992). "Referee in the eye of a storm". The Independent on Sunday.

- ^ "Conversation with Justice Richard Goldstone – p. 1 of 7". Globetrotter.berkeley.edu. 25 July 2003. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "Judges – Justice Richard Goldstone". Constitutional Court of South Africa. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "1,200 to meet here in ORT convention". Chicago Sun-Times. 15 October 1987.

- ^ Eldar, Akiva (6 May 2010). "Richard Goldstone: I have no regrets about the Gaza war report". Haaretz.

- ^ a b c d Bass, Gary Jonathan (2002). Stay the hand of vengeance: the politics of war crimes tribunals. Princeton University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-691-09278-2.

- ^ a b c Hagan, John (2003). Justice in the Balkans: prosecuting war crimes in the Hague Tribunal. University of Chicago Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0-226-31228-6.

- ^ a b 29 Isr. L. Rev 250 (1995). The Contribution of Jewish Lawyers to the Administration of Justice in South Africa; Zimmermann, Reinhard

- ^ Davis, Dennis; Le Roux, Michelle (2009). "Introduction". Precedent & Possibility: the (ab)use of law in South Africa. Juta and Company Ltd. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-1-77013-022-7.

- ^ Tigar, Michael E. (2002). Fighting injustice. American Bar Association. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-59031-015-1.

- ^ Gardner, John (1997). Politicians and apartheid: trailing in the people's wake. HSRC Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7969-1821-5.

- ^ "Transcript of Interview with Geoffrey Budlender" (PDF). Carnegie Corporation Oral History Project. 7 August 1999.

- ^ "1,700 Blacks Reinstated by South African Hospital". Reuters. 25 November 1985.

- ^ "Judge frees political prisoner in S. Africa". Houston Chronicle. 8 July 1986.

- ^ Margolick, David (16 August 1989). "Breaking One of South Africa's Barriers". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Meintjes, Garth. "Goldstone, Richard". In Shelton, Dinah (ed.). Encyclopedia of genocide and crimes against humanity, Volume 1.

- ^ 19 Cardozo L. Rev. 1047 (1997–1998). To Resign or Not to Resign; Ellmann, Stephen

- ^ Elgot, Jessica (6 May 2010). "Goldstone responds to 'death penalty' allegations". The Jewish Chronicle.

- ^ Parker, Peter; Mokhesi-Parker, Joyce (1998). In the shadow of Sharpeville: apartheid and criminal justice. NYU Press. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0-8147-6659-0.

- ^ Judge Goldstone's dark past Tehiya Barak, Ynet, 05.06.10

- ^ Eldar, Akiva (6 May 2010). "Richard Goldstone: I have no regrets about the Gaza war report Israel News". Haaretz. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ a b c McDonough, Challiss (2 October 2003). "SAF/GOLDSTONE (L-O)". Voice of America.

- ^ Kraft, Scott (2 September 1990). "S. Africa Police Blamed in Fatal Shootings of Black Protesters Last March". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Renfrew, Barry (1 September 1990). "Judicial Report: Police Killed Blacks Without Reason". Associated Press.

- ^ a b c Ottaway, David B. (12 July 1992). "South African Judge Makes His Mark With Evenhanded Probe of Violence". The Washington Post.

- ^ Greenberg, Melanie C.; Barton, John H.; McGuinness, Margaret E., eds. (2000). Words over war: mediation and arbitration to prevent deadly conflict. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-8476-9892-9.

- ^ Kerr, Rachel (2004). The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia: an exercise in law, politics, and diplomacy. Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-19-926305-9.

- ^ a b Battersby, John (10 February 1993). "Safety Valve for S. Africa Tension". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1998). "Chapter 4: Institutional Hearing: The Legal Community". Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report. Vol. 4. Cape Town. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-620-23079-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Hazan, Pierre (2004). Justice in a time of war: the true story behind the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-1-58544-377-2.

- ^ Stephen, Chris (2004). Judgement day: the trial of Slobodan Milošević. Atlantic Books. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-1-84354-154-7.

- ^ Nolan, Stephanie (18 October 1999). "The Genocide-Buster". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Horne, William (September 1995). "The Real Trial of the Century". The American Lawyer: 7.

- ^ Hagan, p. 68, 71–72

- ^ Gillot, Sabine (29 September 1996). "Goldstone ends stormy mandate as war crimes prosecutor". Agence France-Presse.

- ^ Peskin, Victor (2008). International justice in Rwanda and the Balkans: virtual trials and the struggle for state cooperation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-0-521-87230-0.

- ^ Hagan, p. 134

- ^ Peskin, pp. 44–45

- ^ Hagan, p. 220

- ^ Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch (17 May 2009). "US: Ask Israel to Cooperate with Goldstone Inquiry". Hrw.org. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "War on Gaza Day 17" (in Arabic). Al Jazeera. 1 December 2009. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (3 April 2009). "Richard J. Goldstone Appointed to Lead Human Rights Council Fact-finding Mission on Gaza Conflict". OHCHR. Archived from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ a b Nebehay, Stephanie (3 April 2009). "South African to head U.N. rights inquiry in Gaza". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. The archived article includes photo.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict". .ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ Ephraim, Adrian (12 October 2009). "They show courage under fire". The Star. Johannesburg.

- ^ Dixon, Robyn; Boudreaux, Richard (12 April 2009). "S. African on the hot seat". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Newspapers. Johannesburg.

- ^ "Goldstone: Israel should cooperate". The Jerusalem Post. 16 July 2009.

- ^ Text of Resolution S-9/1 – the appointment of the mission followed the adoption on 12 January 2009 Archived 19 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Federman, Josef (19 October 2009). "Jurist: Ties to Israel obligated war crimes probe". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "Ethics and War: 'Civilians in War Zones' (panel discussion)". Stanford University. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Golstone, Richard J.; Campbell, James & Berkowitz, Peter (20 January 2011). Civilians in War Zones (MP3). Stanford University. Event occurs at 30:20–31:30. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Khoury, Jack; Ravid, Barak (17 October 2009). "PA 'won't oppose war crimes trials for Hamas militants'". Haaretz. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ Russell, Cecilia (22 January 2010). "Pair of legal heavyweights defend Goldstone". The Star. Johannesburg.

- ^ Judge Goldstone defends role, but feels distressed

- ^ "Honourable Mr Justice Richard GOLDSTONE". Whoswhosa.co.za. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "New Job for Prosecutor". The New York Times. Associated Press. 26 March 1996.

- ^ Cembi, Nomusa (8 September 2006). "Dikgang Moseneke to be Wits chancellor". Independent Online (South Africa).

- ^ a b c d "Biography of Richard J Goldstone". Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "GW-Oxford Program Targets Human Rights". GW Magazine. Washington, D.C.: George Washington University. September 2006.

- ^ Justice Richard Goldstone, Weissberg Chair in International Studies 2006 – 2007

- ^ "Richard J. Goldstone to Lead Human Rights Commission Fact-Finding Mission on Gaza Conflict". Law.fordham.edu. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellows Program". Council of Independent Colleges. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ "Salzburg Global Seminar Board of Directors".

- ^ "PHR Board of Directors – Justice Richard J. Goldstone". Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ "Former World ORT president wins international award". World ORT. 7 November 2008. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ a b Selig, Abe (5 June 2010). "Goldstone stripped of honorary Hebrew U governorship". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Ben Gedalyahu, Tzvi (27 April 2010). "Demand that Hebrew U. Dismiss Judge Goldstone from Board". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Rocker, Simon & Rocker, Simon (1 June 2010). "Judge Goldstone removed from Hebrew University board". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ "Frank Donaghue Congratulates Justice Richard Goldstone on MacArthur Award for International Justice". Physicians for Human Rights.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Honorary Degrees | Whittier College". www.whittier.edu. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "First Spinoza Fellow Richard Goldstone". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 8 April 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "Honorary Members". Awards. Association of the Bar of the City of New York. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ Muller, Eli (7 June 2000). "World ORT president: Israel, S. Africa face similar problems". The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ "Nelson Mandela Iconic Leader". Jewish Daily Forward date: December, 2013.

- ^ "Opinion | Israel and the Apartheid Slander". The New York Times. 31 October 2011. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

Further reading and resources

- Hawthorne, Peter (11 December 2000). "The Cape Crusader". TIME Europe. 156 (24). Archived from the original on 24 January 2001.

- Kreisler, Harry (1997). "Law and the Search for Justice: Conversations with Justice Richard J. Goldstone". Conversations with History. Institute of International Studies, UC Berkeley. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2004.

- Leadel.NET, European Jewish Congress (2010). "Interview: Richard Goldstone". Leadel.NET. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021.

- Physicians for Human Rights (2009). "PHR Board of Directors: Richard J. Goldstone". Physicians for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- Williams, Ian (30 December 2009). "The NS Interview: Richard Goldstone". New Statesman.

- Lecture transcript and video of Goldstone's speech at the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice at the University of San Diego, October 2003

- 1938 births

- Living people

- Apartheid government

- 20th-century South African judges

- South African Jews

- Alumni of King Edward VII School (Johannesburg)

- University of the Witwatersrand alumni

- White South African anti-apartheid activists

- South African anti-apartheid activists

- Harvard Law School faculty

- Beloit College faculty

- New York University faculty

- Fordham University faculty

- International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda prosecutors

- International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia prosecutors

- Judges of the Constitutional Court of South Africa

- South African people of English descent

- South African people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- People from Boksburg

- South African Senior Counsel

- South African officials of the United Nations

- Chancellors of the University of the Witwatersrand

- 21st-century South African judges

- Fellows of St John's College, Cambridge