Helluland

| Part of a series on the |

| Norse colonization of North America |

|---|

|

Helluland (Old Norse pronunciation: [ˈhelːoˌlɑnd]) is the name given to one of the three lands, the others being Vinland and Markland, seen by Bjarni Herjólfsson, encountered by Leif Erikson and further explored by Thorfinn Karlsefni Thórdarson around AD 1000 on the North Atlantic coast of North America.[1] As some writers refer to all land beyond Greenland as Vinland; Helluland is sometimes considered a part of Vinland.[citation needed]

Etymology

[edit]

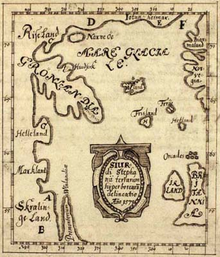

• Land of the Risi (a mythical location)

• Greenland

• Helluland (Baffin Island)

• Markland (the Labrador Peninsula)

• Land of the Skræling (location undetermined)

• Promontory of Vinland (the Great Northern Peninsula)

The name Helluland was given by Leif Erikson during his voyage to Vinland according to the Greenland Saga and means "Land of Flat Rocks/Stones" in Old Norse.[3]

According to the sagas

[edit]Helluland was said to be the first of three lands in North America visited by Eriksson. He decided against trying to settle there because he found the land inhospitable. He continued south to Markland (probably Labrador) and Vinland (possibly Newfoundland).[4]

The Saga of Erik the Red, 1880 translation into English by J. Sephton from the original Icelandic 'Eiríks saga rauða'.

"They sailed away from land; then to the Vestribygd and to Bjarneyjar (the Bear Islands). Thence they sailed away from Bjarneyjar with northerly winds. They were out at sea two half-days. Then they came to land, and rowed along it in boats, and explored it, and found there flat stones, many and so great that two men might well lie on them stretched on their backs with heel to heel. Polar-foxes were there in abundance. This land they gave name to, and called it Helluland (stone-land)."[3]

In the Saga of Halfdan Eysteinsson (Hálfdanar saga Eysteinssonar), written no earlier than the mid-14th century a fragment says:[5]

"Ragnar brought Helluland's obygdir under his sway and destroyed all the giants there..."

Written in the last half of the 13th century an anonymous Icelandic fornaldarsaga, describes the attempts of Örvar-Oddr and his son Vignor to track down an enemy named Ogmund:[6][7]

"I will tell you where Ogmund has gone. He has gone into the Skuggifjord (Hudson Strait), it is in Helluland's Obygdir (uninhabited regions)... he has gone there because he wishes to escape you. But now you may track him to his house if you wish and see what comes of it."

"Thereupon he (and his son Vignor in separate ships) sailed until they came into the Greenland Sea (which lay between Iceland and Greenland) when they turned south and sailed around the land and to the west... They sailed then until they came to Helluland and laid their course into the Skuggifjord..."

"When they reached the land (which they were seeking in the Skuggifjord) father and son went ashore and walked until they saw a fortified structure very strongly built..."

In ancient Icelandic scholarship

[edit]According to a footnote in Arthur Middleton Reeves' The Norse Discovery of America (1906), "the whole of the northern coast of America, west of Greenland, was called by the ancient Icelandic geographers Helluland it Mikla, or Great Helluland; and the island of Newfoundland simply Helluland, or Litla Helluland."[8]

Current scholarly opinion

[edit]

The Icelandic Saga of Erik the Red and the Greenland Saga characterized Helluland as a land of flat stones (Old Norse: hella). Most scholars agree that Helluland corresponds to Baffin Island in the present-day Canadian territory of Nunavut.[9]

From the testimony of the sagas, the Norse explorers probably made contact with the native Dorset culture of the region, people whom the sagas term skrælings.[citation needed] Historians[who?] suggest the contact had no major cultural ramifications for either side.

Patricia Sutherland, of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, found in the museum's collections yarn collected in archaeological digs on Baffin Island that corresponded to that found in Norse settlements in Greenland,[10] which led her to explore in depth the potential that the Norse had settled on Baffin Island. Over a number of years searching in collections and digging at sites such as Tanfield Valley, she found numerous artifacts, such as tally sticks, signs of iron and bronze metallurgy and whetstones used for sharpening metal tools, and European-style masonry and turf construction, which indicated to her that the Vikings had been on Baffin for an extended period and likely had an established trading relationship with the Dorset natives in the area.

Sutherland's new findings further strengthen the case for a Viking camp on Baffin Island. "While her evidence was compelling before, I find it convincing now," said James Tuck, professor emeritus of archaeology, ... at Memorial University."[11]

Sutherland and the Helluland Archaeology Project among others[who?] have identified several potential pre-Columbian European archaeological sites including Tanfield Valley, Avayalik at the far north of the Labrador Peninsula, Willows Island at the southern part of Baffin Island, Pond Inlet (Nunguvik) in the far north of Baffin Island.[12] When Sutherland was asked if she might have been fired from the Canadian Museum of Civilization, now the Canadian Museum of History, because her research was out of step with government views of Canadian history, Sutherland agreed.[13]

Sir Wilfred Grenfell, a medical missionary and scholar living in Newfoundland and Labrador in the early 20th century wrote in his work "The Romance of Labrador" that Helluland likely corresponds to Kangalaksiorvik Bay, a fiord around 100 miles (161 km) south of the Torngat Mountains. He described its south side as home to "endless acres of flat stones", south of which lie the wooded Markland and, further south, Vinland the Good.[14]

In 2018, Michele Hayeur Smith of Brown University, who specializes in the study of ancient textiles, wrote that she does not think the ancient Arctic people, the Dorset and Thule, needed to be taught how to spin yarn: "It's a pretty intuitive thing to do."[10] Journal of Archaeological Science, August 2018:

". . . the date received on Sample 4440b from Nanook clearly indicates that sinew was being spun and plied at least as early, if not earlier, than yarn at this site. We feel that the most parsimonious explanation of this data is that the practice of spinning hair and wool into plied yarn most likely developed naturally within this context of complex, indigenous, Arctic fiber technologies, and not through contact with European textile producers. [. . .] Our investigations indicate that Paleoeskimo (Dorset) communities on Baffin Island spun threads from the hair and also from the sinews of native terrestrial grazing animals, most likely musk ox and arctic hare, throughout the Middle Dorset period and for at least a millennium before there is any reasonable evidence of European activity in the islands of the North Atlantic or in the North American Arctic."[15]

William W. Fitzhugh, Director of the Arctic Studies Center at the Smithsonian Institution, and a Senior Scientist at the National Museum of Natural History, wrote that there is insufficient published evidence to support Sutherland's claims, and that the Dorset were using spun cordage by the 6th century.[16] In 1992, Elizabeth Wayland Barber wrote that a piece of three-ply yarn that dates to the Paleolithic era, that ended about 10,000 BP, was found at the Lascaux caves in France. This yarn consisted of three s-twist strands that were z-plied, much like the way a three-ply yarn is made now, whereas the Baffin Island yarn was a simple two-ply yarn.[17] The eight sod buildings and artifacts found in the 1960s at L'Anse aux Meadows, located on the northern tip of Newfoundland, remains the only confirmed Norse site in North America outside of those found in Greenland.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ National Museum of Natural History, Arctic Studies Center. Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga Archived 2015-12-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ http://www.myoldmaps.com/renaissance-maps-1490-1800/4316-skalholt-map/4316-skalholt-map.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b "The Saga of Erik the Red". The Icelandic Saga Database. Sveinbjörn Þórðarson. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

This land they gave name to, and called it Helluland (stone-land).

- ^ "Is L'Anse aux Meadows Vinland?". L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. 12 December 2003. Archived from the original on 22 May 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ Hardman, George L. Hálfdanar saga Eysteinssonar.

- ^ Reeves, Arthur Middleton (1890). The Finding of Wineland the Good: The History of the Icelandic Discovery of America. H. Frowde. p. 91.

- ^ Hermann Palsson, Paul Edwards (1985). Seven Viking Romances. 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2: Penguin Books Canada Ltd. pp. 86. ISBN 978-0-14-044474-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "The Norse Discovery of America: Book II. Icelandic Records: Saga of Thorfinn Karlsefne".

- ^ Jónas Kristjánsson et al. (2012) "Falling into Vínland", Acta Archaeologica 83, pp. 145-177

- ^ a b Weber, Bob (22 July 2018). "Ancient Arctic people may have known how to spin yarn long before Vikings arrived". Old theories being questioned in light of carbon-dated yarn samples. CBC. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

... Michele Hayeur Smith of Brown University in Rhode Island, lead author of a recent paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Hayeur Smith and her colleagues were looking at scraps of yarn, perhaps used to hang amulets or decorate clothing, from ancient sites on Baffin Island and the Ungava Peninsula. The idea that you would have to learn to spin something from another culture was a bit ludicrous," she said. "It's a pretty intuitive thing to do.

- ^ Pringle, Heather (October 19, 2012). "Evidence of Viking Outpost Found in Canada". National Geographic. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012.

- ^ "Helluland Archaeology Project". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ Stueck, Wendy; Taylor, Kate (4 December 2014). "Canadian Museum of History reveals researcher was fired for harassment". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

On the program, host Carol Off interviewed Dr. Sutherland [...] Off asked Dr. Sutherland whether she might have been fired from the Canadian Museum of Civilization (which was renamed the Canadian Museum of History last year) because her research was out of step with government views of Canadian history. Sutherland agreed [...]

- ^ Grenfell, Sir Wilfred Thomason (1934). The Romance of Labrador (1st ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishers. p. 59.

- ^ Smith, Michèle Hayeur; Smith, Kevin P.; Nilsen, Gørill (August 2018). "Journal of Archaeological Science" (PDF). Dorset, Norse, or Thule? Technological Transfers, Marine Mammal Contamination, and AMS Dating of Spun Yarn and Textiles from the Eastern Canadian Arctic. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/J.JAS.2018.06.005. hdl:10037/14501. S2CID 52035803. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-13. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

However, the date received on Sample 4440b from Nanook clearly indicates that sinew was being spun and plied at least as early, if not earlier, than yarn at this site. We feel that the most parsimonious explanation of this data is that the practice of spinning hair and wool into plied yarn most likely developed naturally within this context of complex, indigenous, Arctic fiber technologies, and not through contact with European textile producers.

- ^ Armstrong, Jane (20 November 2012). "Vikings in Canada?". A researcher says she's found evidence that Norse sailors may have settled in Canada's Arctic. Others aren't so sure. Maclean's. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

In fact, Fitzhugh thinks the cord at the centre of Sutherland's "eureka" moment is a Dorset artifact. "We have very good evidence that this kind of spun cordage was being used hundreds of years before the Norse arrived in the New World, in other words 500 to 600 CE, at the least," he says.

- ^ Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1992) Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, Princeton University Press, "We now have at least two pieces of evidence that this important principle of twisting for strength dates to the Palaeolithic. In 1953, the Abbé Glory was investigating floor deposits in a steep corridor of the famed Lascaux caves in southern France [...] a long piece of Palaeolithic cord [...] neatly twisted in the S direction [...] from three Z-plied strands [...]" ISBN 0-691-00224-X

- ^ Jarus, Owen (6 March 2018). "Archaeologists Closer to Finding Lost Viking Settlement". Live Science. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

If Hóp is found it would be the second Viking settlement to be discovered in North America. The other is at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland.