Delaware Wedge

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2013) |

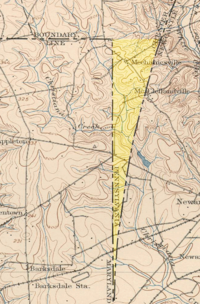

The Wedge (or Delaware Wedge) is a 1.068-square-mile (684-acre; 2.77 km2)[1] tract of land along the borders of Delaware, Maryland and Pennsylvania. Ownership of the land was disputed until 1921; it is now recognized as part of Delaware.[2] The tract was created primarily by the shortcomings of contemporary surveying techniques when the boundaries were defined in the 18th century. It is bounded on the north by an eastern extension of the east–west portion of the Mason–Dixon line, on the west by the north–south portion of the Mason–Dixon line, and on the southeast by the Twelve-Mile Circle around New Castle, Delaware. The crossroads community of Mechanicsville, Delaware, lies within the area today.

History

[edit]Colonization and establishment of ownership

[edit]

The original 1632 charter for the Province of Maryland gave the Calverts what is now called the Delmarva Peninsula above the latitude of Watkins Point, Maryland up to the 40th parallel. A small Dutch settlement, Zwaanendael (1631–32), was within their territory, as were the later New Sweden and New Netherland settlements along the Delaware Bay and Delaware River. Although the Calverts publicly stated that they wanted the settlements removed, they did not confront them militarily because of the foreign policy implications for the Crown.

In 1664, Prince James, Duke of York, the brother of King Charles II, removed foreign authority over these settlements, but in the process the Crown eventually decided that the area around New Castle and the land below it on the Delaware Bay should be separated from Maryland and administered as a new colony.

In 1681, William Penn received his charter for the Province of Pennsylvania. This charter granted him land west of the Delaware River and north of the 40th parallel, but land within 12 miles (19 km) of New Castle was excluded. This demonstrates how poorly-charted this area was, as New Castle is actually about 25 miles (40 km) south of the 40th parallel. The Penns later acquired the New Castle lands from the Duke of York, which they called the Three Lower Counties and later became known as Delaware Colony. However, it remained a distinct possession from Pennsylvania.

Border agreement

[edit]

The exact, and even approximate, boundaries of these three colonies remained in considerable dispute for the next 80 years. After settling Philadelphia and the surrounding area, the Penns discovered that it was actually below the 40th parallel, and tried to make claims to the land south of Philadelphia. The Calverts had failed to confirm their hold on their grant, either by surveying it or by establishing loyal settlers. The main progress during the 1750s was to survey the Twelve-Mile Circle around New Castle as the northern and western boundary of Delaware and to establish the Transpeninsular Line as its southern border. An agreement was also reached between the Calverts and Penns that the boundary between their respective possessions would be:

- The Transpeninsular Line from the Atlantic Ocean to its midpoint to the Chesapeake Bay. According to NOAA, the Middle Point monument is at 38° 27′ 35.8698″ N, 75° 41′ 38.4554″ W (NAD27) or 38° 27′ 36.29213″ N, 75° 41′ 37.18951″ W (NAD83). The monument is a short distance east of U.S. Route 50 near Mardela Springs, Maryland.

- A line segment which was tangent to the western side of the Twelve-Mile Circle and which extended to the midpoint of the Transpeninsular Line, of minimal length. (This line is uniquely determined by geometry)

- A North Line from the Tangent Point to a line which runs 15 miles (24 km) south of Philadelphia (approximately 39° 43′ N latitude).

- The aforementioned parallel at 39° 43′ N, which was reached as a compromise to the 40th parallel and the desire to accommodate Philadelphia within Pennsylvania.

- Should any land within the Twelve-Mile Circle fall west of the North Line, it would remain part of Delaware. (This indeed was the case, and this boundary segment is known as the Arc Line.)

Maryland would be south or west of all of these borders. Penn's possessions would be north or east of them.

The 39° 43′ N parallel united with the Tangent Line would become (once surveyed) the Mason–Dixon Line.

Discovery of the Wedge and basis of dispute

[edit]When this was agreed upon, the final shape of the border was unknown to the involved parties. Mostly because of the difficulty of surveying the Twelve-Mile Circle tangent point and the Tangent Line, astronomer Charles Mason and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon were hired. This complex border became known as the Mason–Dixon line. There turned out to be a small wedge of land between 39° 43′ N latitude, the Twelve-Mile Circle, and the North Line. The top is roughly 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km), and the side is roughly 3 miles (4.8 km) long. Maryland clearly no longer had a claim to the Wedge, as it is east of the Mason–Dixon Line, and since the Penns owned both Pennsylvania and Delaware, there was no particular incentive to determine which possession it was a part of, at least until they became separate states.

- Pennsylvania claimed the Wedge because it was beyond the Twelve-Mile Circle and past the Maryland side of the Mason–Dixon Line, therefore part of neither Maryland nor Delaware.

- Delaware claimed the Wedge because it was never intended that Pennsylvania should go below the northern border of Maryland (which originally ran at 40° N all the way to the Delaware River). The North Line is logically an extension of the Tangent Line and therefore should separate Maryland and Delaware. Even though the Wedge is outside the Twelve-Mile Circle, because it is south of the 39° 43′ N compromise line, it should not be part of Pennsylvania.

Mason and Dixon actually began surveying the Maryland–Pennsylvania border line at the Delaware River, or at least fixed the longitude of the intersection of 39° 43′ N and the river. Even though this point is within the Twelve-Mile Circle, the western boundary of Pennsylvania was to be five degrees of longitude west of it, and Mason and Dixon were to survey the Maryland line to Pennsylvania's western border.

Resolution

[edit]By simple geometry, the Wedge fit more logically as a part of Delaware, which exercised jurisdiction of the area. In 1849, Lt. Col. J. D. Graham of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers resurveyed the northeast corner of Maryland and the Twelve-Mile Circle.[3] This survey reminded Pennsylvania of the issue and they once again claimed the Wedge. Delaware ignored the claim. In 1892, W.C. Hodgkins of the Office of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey monumented an eastward extension of the Maryland–Pennsylvania border, and created the "Top of The Wedge Line". In 1921 both states settled on this boundary, giving ownership of the Wedge – in full – to Delaware.

Contemporary routes

[edit]Delaware Route 273 and Delaware Route 896 cut across the Wedge. Route 896 passes very close to the tripoint, and actually passes through Maryland before entering Pennsylvania. Hopkins Road, a side road off Route 896, passes near the northeast corner of the Wedge and passes from Delaware into Pennsylvania and back into Delaware at this point. The name of the road bordering the Wedge to the east is Wedgewood Road.[4] As a convenience to motorists, the highway retains route number 896 in Delaware, Maryland and Pennsylvania.

See also

[edit]- Free State of Bottleneck

- Gore (surveying)

- Mason–Dixon line

- Neutral Moresnet

- Delaware–Maryland–Pennsylvania Tri-State Point

References

[edit]- ^ Soniak, Matt (February 8, 2011). "Livin' on the Wedge: The Long, Strange History of a Disputed Border". Mental Floss. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Delaware Federal Writers' Project (1976) [1938]. Delaware: A Guide to the First State. North American Book Dist LLC. pp. 457–459. ISBN 978-0-403-02160-4.

- ^ J. D. Graham papers. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library Repository, Yale University.

- ^ "A brief history of the Mason-Dixon Line". Archived from the original on 11 February 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

External links

[edit]- Borders of Delaware

- Pre-statehood history of Pennsylvania

- Internal territorial disputes of the United States

- Border irregularities of the United States

- Borders of Pennsylvania

- Borders of Maryland

- Geography of New Castle County, Delaware

- Geography of Chester County, Pennsylvania

- Border tripoints

- 1921 disestablishments in the United States

- Mason–Dixon line