Hooiberg

| Hooiberg | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

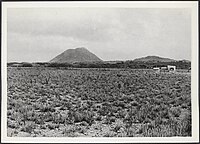

Hooiberg photographed from the Casibari rocks | |||||||||||||||

| Highest point | |||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 165 m (541 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Prominence | 165 m (541 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 12°31′01″N 69°59′42″W / 12.517°N 69.995°W | ||||||||||||||

| Naming | |||||||||||||||

| English translation | Haystack | ||||||||||||||

| Language of name | Dutch | ||||||||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Location | |||||||||||||||

| District | Santa Cruz | ||||||||||||||

| Geology | |||||||||||||||

| Mountain type | Conical hill | ||||||||||||||

| Rock type | Hooibergite | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Hooiberg (Dutch: /ˈɦojbɛrx/ ()) is a distinctively shaped, 165 m (541 ft) conical hill located at the heart of the island of Aruba. This geological formation is a prominent and recognizable landmark that has long captured the attention of locals and visitors alike—Hooiberg is Aruba's centerpiece.[2]

Name

[edit]

Many old place names (toponyms) on Aruba have indigenous origins, but the language that was spoken in the past has been lost to posterity.[3] Historically, this hill was known as Orcuyo, an old indigenous name.[4]

The hill has had various names throughout the years. In Spanish, it was called Cerro de Paja ó Pan de Azucar, meaning "hill of straw", "sugar bread", or "sugarloaf".[5][6] Sugarloaf refers to refined sugar shaped into a tall conical form, which was sold before the 1900s. Hooiberg is one of several formations named after Cerro Pan de Azucar (such as Pan de Azucar Island in the Philippines or Sugarloaf Mountain in Brazil). The Dutch gave it their own name, and the spelling of Hooiberg has changed over time, appearing as Hooy berg and Hooij-berg.[7][8] The name itself is a combination of hooi, meaning "hay", and berg, meaning "mountain", "mound" or "pile".[9] The hill is said to resemble a loose haystack or a hay barrack (Dutch barn), which explains the name Hooiberg.[10][11]

Geology

[edit]Landscape

[edit]Hooibergiet in flat quartz-diorite landscape.

Despite its name (Dutch: -berg ("mountain")), Hooiberg is more accurately described as a hill rather than a mountain. It's worth noting that Hooiberg is not the tallest geological formation on the island; in fact, that is a common misconception.[6] Jamanota, which stands at 188 m (617 ft), holds that title.[12] Nevertheless, Hooiberg is a prominent natural and cultural landmark in the otherwise flat diorite/tonalite landscape of Aruba. This flat landscape evolved through diorite erosion (denuded) to a relatively low level with an average altitude of 40 m (130 ft) above sea level. In this area numerous pillow-structures consisting of large-rounded diorite blocks are found, namely Casibari and Ayo rock formations.[13] Three distinct hills are preserved by selective erosion in this area; the conical Hooiberg (165m), the Seroe Bientoe (85m), Wara Wara (98m).[12]

Rock type

[edit]Hooiberg is a Cretaceous-era tonalitic batholith that outcrops on Aruba consisting of tonalite with subordinate and comagmatic trondhjemite, diorite, gabbro, norite, and a dark-colored (melanocratic), hydrous, igneous rock termed hooibergite, or hornblende-rich mela-diorite.[14][15] It contains large (~2 cm) hornblende crystals in a matrix of poikiolitic plagioclase enclosing augite.[15] Named after the Hooiberg hill—Hooibergiet or Hooibergite in Dutch and English, respectively.[13][16][17] The hooibergite is observed as the final magmatic phase, succeeding the formation of gabbro and tonalite/diorite.[18]

History

[edit]Aruba seen by the Dutch

[edit]Aruba was likely first sighted by Dutch privateer, Pieter Schouten, on April 24, 1624, during an expedition by the West India Company. The expedition sailed past several islands, including Aruba but did not go ashore. Schouten noted that Aruba had a mountain. "Hooiberg, which he signaled, will always remain a beacon to all seafarers."[19]

Joannes de Laet, a Dutch geographer and director of the Dutch West India Company, describe in his book Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien (1630) that "Aruba... is a sparsely populated land with two small mountains. One of the mountains resembles a sugarloaf and is approximately five miles away. It is inhabited by a few Indians and some Spaniards."[20][21]

Aruba seen by the English

[edit]David Middleton (1706) described the unfortunate landing of a group of sailors from Captain Sir Michael Geare's ship on Aruba in 1601: "On the 29th of this month (July) we landed on Aruba to fetch fresh water, where seven of our men were killed by the Indians. We lay with our ship half a mile from the shore in 5 fathoms of water. The land protrudes on this side to the north and on the other side to the southeast towards the south; in the middle of the island, from the south, there is a high mountain."[22]

Tragedy at Hooiberg 83

[edit]In the early morning hours of October the 13th, 1990, a tragedy struck at Hooiberg. The night before, Aruba experienced extreme weather bringing with it heavy rain, thunder, lightning and flooding. Mr. and Mrs. Frank were in their bedroom when the dog barked as a wave of thunder and lightning hit. This moment prompted Mr. Frank to walk out of the bedroom. At around 3 AM, neighbors heard a loud rumbling noise. They called the local emergency call center, and within minutes, first responders arrived to find a harrowing scene. Mr Frank is covered in mud desperately searching for his wife, who is still inside the half-crushed house. The hazardous environment and extreme weather made it impossible for anyone to search for her. Most bystanders only bore witness to the scene, fearing they might step on her body. It took excavators and tools to finally reach her, whose body was found at 8 AM buried under a pile of mud and a 1.5-meter-wide (~5 ft.) boulder. The Frank family had just put their house on the market and had purchased a new home, planning to move soon. The house at Hooiberg 83 was demolished and the plot has been left empty to this day.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

The concrete staircase

[edit]In the past century, Hooiberg was a popular starting point for surveying, and indigenous peoples also used the conical hill as an orientation point and watchtower to survey the sea, as evidenced by the shell artifacts found there. In modern times, the hill has been utilized for different purposes, such as hosting radio and television masts and a navigation light. To facilitate the maintenance of these instruments, a remarkable structure was built in 1951—a concrete staircase with around 900 steps. Despite the innovative idea, few local citizens advocated for its construction. However, architect Eduardo Tromp took the risk and built the high staircase within three months without a blueprint.[2] The result is a remarkable feat of engineering that has become a popular attraction of approximately 587 (2022) steps and has undergone multiple reconstructions and upkeep.[29][30]

Culture and agriculture

[edit]Coat of arms of Aruba

[edit]The Hooiberg and Aloe vera were officially adopted as emblems on the coat of arms on November 15, 1955. The upper right quadrant, positioned next to the Aloe vera, depicts Hooiberg in green, representing Aruba rising from the barry (blazon: patterns of horizontal stripes of altering color) wavy sea. The elevation of Hooiberg on the shield symbolizes the island's history of food crop cultivation. Hooiberg is part of a triangle of peaks, including Seroe Biento and Cero Canashito that form a watershed area at their base. The locale has always been one of the most reliable agricultural areas on the island.[31]

Pre-refinery industries

[edit]Initiatives were taken in the area of Canashito (Santa Cruz) in 1830 to stimulate settlement and agriculture production. They successfully cultivated crops, fruit, and seed-bearing trees on 2 hectares (4.9 acres) of land.[32] Hooiberg's favorable condition made it suitable for agriculture, unlike most parts of the island, including Jamanota, which were generally unreliable for cultivation.[33][31]

Aloe industry

[edit]The aloe industry is recognized as Aruba's most important industry due to the history of resource exploitation that had a substantial impact on the landscape.[32] Since the arrival of Spanish colonization, the landscape in Aruba underwent fundamental changes, including deforestation and the introduction of free-roaming herds that graze on the land.[34]

Aloe vera was introduced to Aruba in 1840 and became a major producer and exporter of the plant known for its high quality due to high levels of aloin. Aloe cultivation was predominantly located in southwest coastal areas, particularly on limestone terraces. The deforestation of dyewood (Haematoxylum brasiletto) a century earlier may have contributed to the liming (calcium-rich soil), provided the ideal conditions for aloe to thrive.[35] By 1911, agricultural activities covered nearly the entire central part of Aruba, particularly on the quartz-diorite landscape.[36] In 1912, Aruba exported 375,000 kilograms (827,000 pounds) of aloe vera, compared to 920 kilograms (2,030 pounds) from Curaçao and 31,000 kilograms (68,000 pounds) from Bonaire.[37]

Peanut industry

[edit]In the 18th century, peanuts imported from Curaçao by the Dutch West India Company were brought to Aruba, where they grew into an important industry. The difference in soil made Aruba for a long time the “peanut island”. Peanut-growing became a favored means of livelihood in areas such as Hooiberg, including Noord and near Seroe Cristal.[38]

Climbing record

[edit]While Rudy Carti holds the record for ascending the Hooiberg fifty times within seventeen hours since 1991, it is important to acknowledge the harm he caused others. In 2021, Carti was convicted of sexual abuse.[39] Although he originally undertook the climbing challenge not only to set a record but also to help the "Yuda Bo Prohimo" foundation provide Christmas meals to the less fortunate, it's important to prioritize the voices and experiences of the survivors of his abuse over his climbing achievement.[40] Nonetheless, the climb to the volcanic peak remains a challenging and rewarding experience, with a still-daunting steep staircase.[41]

In 2017, Ricardo Croes, an Aruban politician, climbed Hooiberg twenty-one times in six hours to raise funds for charitable causes, such as the children's home "Casa Cuna" and the "Pasadia Briyo di Solo" foundation for the cognitively disabled in Aruba.[42]

Hooiberg views

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hooiberg". City Population. 2020-10-01. Hooiberg. Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ a b "Aruba Nostra (1966-1969) - Biblioteca Nacional Aruba (BNA)". Coleccion Aruba. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Hartog, Dr. J. (1988). Aruba: Short history (5 ed.). Aruba: van Dorp. p. 34.

- ^ Kock, Adolf (Dufi) (2016-01-05). Un storia di e Indjan Arua.

- ^ "Biblioteca Virtual del Ministerio de Defensa". bibliotecavirtualdefensa.es (in Spanish). 2012. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ a b Teenstra, Marten Douwes (1837). "Aruba", in: De Nederlandsche West-Indische Eilanden in derzelfer tegenwoordigen Toestand (1837) Teenstra.

- ^ "View file | Nationaal Archief". www.nationaalarchief.nl. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Spengler, W.A. van; Raders, R.F. van; VeelWaard, D.; Veelwaard, D. (1827). "Kaart van het eiland Aruba" [Map of the island of Aruba]. Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections (in Dutch). hdl:1887.1/item:53193. Retrieved 2023-05-25.

- ^ "hooiberg", Wiktionary, 2020-09-04, retrieved 2023-03-21

- ^ Sullivan, Lynne M. (2006). Adventure Guide to Aruba, Bonaire & Curaçao. Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 81. ISBN 9781588435729. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ de Gaay Fortman, B. (1934). Curaçao (in Dutch). [s.n.] p. 53.

- ^ a b Westermann, J.H. "Aruba". Leidse Geologische Mededelingen. 5 (1): 709–714 – via Naturalis journals & series.

- ^ a b Westermann, J.H. (1947). "Natuurbescherming op de Nederlandsche Antillen, Haar Ethische, Aesthetische, Wetenschappelijke en Economische Perspectieven". De West-Indische Gids (in Dutch). 28. KITLV, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, Brill: 193–216. doi:10.1163/22134360-90000350. JSTOR 41835324. Retrieved 2023-03-21 – via JSTOR.

- ^ White, Rosalind; Tarney, John; Klaver, Gerard; Ruiz, Arminda (1996). "The Genesis of Primitive Tonalites Associated With An Accreting Cretaceous Oceanic Plateau: The Aruba Batholith and the Aruba Lava Formation" (PDF). 3rd International Symposium on Andean Geodynamics (ISAG): 661–663.

- ^ a b White, R.; Tarney, J.; Kerr, A.; Saunders, A.; Kempton, P.; Pringle, M.; Klaver, G. (1999). "Modification of an oceanic plateau, Aruba, Dutch Caribbean: Implications for the generation of continental crust". Lithos. 46: 43–68. doi:10.1016/S0024-4937(98)00061-9.

- ^ White, R.V., Tarney, J., Klaver, G.T., & Ruiz, A.V. (1996). The genesis of primitive tonalites associated with an accreting cretaceous oceanic plateau : the Aruba batholith and the Aruba lava formation.

- ^ Donnelly, T. W. (1989). Geologic history of the. The geology of North America: an overview, 299.

- ^ White, Rosalind; Tarney, John; Klaver, Gerard; Ruiz, Arminda (1996). "The Genesis of Primitive Tonalites Associated With An Accreting Cretaceous Oceanic Plateau: The Aruba Batholith and the Aruba Lava Formation" (PDF). 3rd International Symposium on Andean Geodynamics (ISAG): 661–663.

- ^ Hartog, Johan (1961). Aruba: Past and Present–From the Time of the Indians until Today. Oranjestad: D.J. de Wit. pp. 40–41.

- ^ Hartog, Johan (1980). Aruba : zoals het was, zoals het werd : van de tijd der Indianen tot op heden (in Dutch). Van Dorp. p. 41.

- ^ Laet, J. de (1630). Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien (in Dutch) (2nd ed.). Leyden: Elzeviers. p. 618.

- ^ Middleton, David (1706). Voyagie na West-Indien, gedaan door David Middelton, met kapiteyn Michael Geare, in 't jaar 1601. Mitsgaders de Scheepts-togt van Georg Weymouth. Gedaan in 't Jaar 1602. Om in het Noord-Westen een opening na China te ontdekken (in Dutch). Leyden: Van de Aa. Archived from the original on 2023-05-01. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Historia di Aruba - 31 aña pasa" [History of Aruba - 31 years ago]. Diario Online. 2021-10-13. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ Cecily (2019-10-13). "E dia cu Hooiberg bin abao" [The day Hooiberg came down]. 24ora.com. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ "Recordando 30 aña pasa cu e baranca a bin abao for di Hooiberg pa destrui un cas y kita bida di habitante" [Remembering 30 years ago when a boulder descended from Hooiberg and destroyed a house and life of inhabitant was taken]. Diario Online. 2020-10-14. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ Cecily (2019-10-13). "E dia cu Hooiberg bin abao". 24ora.com. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ "Rampwoning bij Hooiberg". Amigoe Aruba. 1990-10-15. p. 5.

- ^ Patrick (2020-10-14). "Tragedia na Hooiberg: Famia tabata pendiente pa muda pa un otro cas". 24ora.com. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Overheid, Aruba (2022-10-04). "Beautification project of Hooiberg". www.government.aw. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ^ webmaster@visitaruba.com. "Aruba Landmarks - Hooiberg Mountain - VisitAruba.com". www.visitaruba.com. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

- ^ a b Phalen, John H. (1981). "A Symbolic Analysis of Aruban Aloe: A View of Cultural Continuity and Change". Anthropos. 76 (1/2): 226–230. ISSN 0257-9774. JSTOR 40460301.

- ^ a b Derix, R. (2016b). Landscape series no.2: The history of resource exploitation in Aruba. Spatial and Environmental Statistics - Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS Aruba).

- ^ "Gevonden in Delpher - Tijdschrift van het Aardrijkskundig Genootschap". www.delpher.nl (in Dutch). January 1948. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ NAMA. National Archeological Museum Aruba.

- ^ Hartog, Johan (1961). Aruba: Past and Present–From the Time of the Indians until Today. Oranjestad: D.J. de Wit. pp. 158

- ^ De Busonjé, P. H. (1974). Thesis: Neogene and Quaternary geology of Aruba, Curacao, and Bonaire. Uitgaven Natuurwetenschappelijke Studiekring voor Suriname en de Nederlandse Antillen, no. 78.

- ^ Hartog, Johan (1961). Aruba: Past and Present–From the Time of the Indians until Today. Oranjestad: D.J. de Wit. pp. 159

- ^ Hartog, Johan (1961). Aruba: Past and Present–From the Time of the Indians until Today. Oranjestad: D.J. de Wit. pp. 160.

- ^ Felix (9 October 2021). "Rudy Carti condena na 1 aña di prison y 4 aña sin por traha como fisioterapista". Diario Online. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Entrevista di Dia | Rudy Carti, retrieved 2023-04-06

- ^ Perrett, Kelsey (2018-11-30). "Hooiberg Challenge (Stair Run)". Great Runs. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ NoticiaCla (2017-09-08). "Ricardo Croes (RED) a logra subi Hooiberg 21 biaha, pa un bon causa". NoticiaCla. Retrieved 2023-04-12.