Hoax

A hoax is a widely publicised falsehood created to deceive its audience with false and often astonishing information, with the either malicious or humorous intent of causing shock and interest in as many people as possible.

Some hoaxers intend to eventually unmask their representations as having been a hoax so as to expose their victims as fools; seeking some form of profit, other hoaxers hope to maintain the hoax indefinitely, so that it is only when skeptical people willing to investigate their claims publish their findings, that the hoaxers are finally revealed as such.

History

[edit]Zhang Yingyu's The Book of Swindles (c. 1617), published during the late Ming dynasty, is said to be China's first collection of stories about fraud, swindles, hoaxes, and other forms of deception.[1] Although practical jokes have likely existed for thousands of years, one of the earliest recorded hoaxes in Western history was the drummer of Tedworth in 1661.[2] The communication of hoaxes can be accomplished in almost any manner that a fictional story can be communicated: in person, via word of mouth, via words printed on paper, and so on. As communications technology has advanced, the speed at which hoaxes spread has also advanced: a rumour about a ghostly drummer, spread by word of mouth, will affect a relatively small area at first, then grow gradually. However, hoaxes could also be spread via chain letters, which became easier as the cost of mailing a letter dropped. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century brought down the cost of a mass-produced books and pamphlets, and the rotary printing press of the 19th century reduced the price even further (see yellow journalism). During the 20th century, the hoax found a mass market in the form of supermarket tabloids, and by the 21st century there were fake news websites which spread hoaxes via social networking websites (in addition to the use of email for a modern type of chain letter).

Etymology

[edit]The English philologist Robert Nares (1753–1829) says that the word hoax was coined in the late 18th century as a contraction of the verb hocus, which means "to cheat", "to impose upon"[3] or (according to Merriam-Webster) "to befuddle often with drugged liquor."[4] Hocus is a shortening of the magic incantation hocus pocus,[4] whose origin is disputed.[5][better source needed]

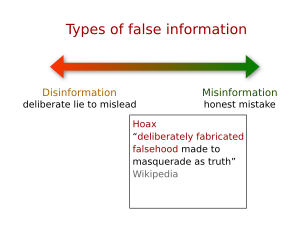

Definition

[edit]

Robert Nares defined the word hoax as meaning "to cheat", dating from Thomas Ady's 1656 book A candle in the dark, or a treatise on the nature of witches and witchcraft.[6]

The term hoax is occasionally used in reference to urban legends and rumours, but the folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand argues that most of them lack evidence of deliberate creations of falsehood and are passed along in good faith by believers or as jokes, so the term should be used for only those with a probable conscious attempt to deceive.[7] As for the closely related terms practical joke and prank, Brunvand states that although there are instances where they overlap, hoax tends to indicate "relatively complex and large-scale fabrications" and includes deceptions that go beyond the merely playful and "cause material loss or harm to the victim."[8]

According to Professor Lynda Walsh of the University of Nevada, Reno, some hoaxes – such as the Great Stock Exchange Fraud of 1814, labelled as a hoax by contemporary commentators – are financial in nature, and successful hoaxers – such as P. T. Barnum, whose Fiji mermaid contributed to his wealth – often acquire monetary gain or fame through their fabrications, so the distinction between hoax and fraud is not necessarily clear.[9] Alex Boese, the creator of the Museum of Hoaxes, states that the only distinction between them is the reaction of the public, because a fraud can be classified as a hoax when its method of acquiring financial gain creates a broad public impact or captures the imagination of the masses.[10]

One of the earliest recorded media hoaxes is a fake almanac published by Jonathan Swift under the pseudonym of Isaac Bickerstaff in 1708.[11] Swift predicted the death of John Partridge, one of the leading astrologers in England at that time, in the almanac and later issued an elegy on the day Partridge was supposed to have died. Partridge's reputation was damaged as a result and his astrological almanac was not published for the next six years.[11]

It is possible to perpetrate a hoax by making only true statements using unfamiliar wording or context, such as in the Dihydrogen monoxide hoax. Political hoaxes are sometimes motivated by the desire to ridicule or besmirch opposing politicians or political institutions, often before elections.

A hoax differs from a magic trick or from fiction (books, film, theatre, radio, television, etc.) in that the audience is unaware of being deceived, whereas in watching a magician perform an illusion the audience expects to be tricked.

A hoax is often intended as a practical joke or to cause embarrassment, or to provoke social or political change by raising people's awareness of something. It can also emerge from a marketing or advertising purpose. For example, to market a romantic comedy film, a director staged a phony "incident" during a supposed wedding, which showed a bride and preacher getting knocked into a pool by a clumsy fall from a best man.[12] A resulting video clip of Chloe and Keith's Wedding was uploaded to YouTube and was viewed by over 30 million people and the couple was interviewed by numerous talk shows.[12] Viewers were deluded into thinking that it was an authentic clip of a real accident at a real wedding; but a story in USA Today in 2009 revealed it was a hoax.[12]

Governments sometimes spread false information to facilitate their objectives, such as going to war. These often come under the heading of black propaganda. There is often a mixture of outright hoax and suppression and management of information to give the desired impression. In wartime and times of international tension rumours abound, some of which may be deliberate hoaxes.

Examples of politics-related hoaxes:

- Belgium is a country with a Flemish-speaking region and a French-speaking region. In 2006, French-speaking television channel RTBF interrupted programming with a spoof report claiming that the country had split in two and the royal family had fled.

- On 13 March 2010, the Imedi television station in Georgia broadcast a false announcement that Russia had invaded Georgia.[13]

Psychologist Peter Hancock has identified six steps which characterise a truly successful hoax:[14]

- Identify a constituency – a person or group of people who, for reasons such as piety or patriotism, or greed, will truly care about your creation.

- Identify a particular dream which will make your hoax appeal to your constituency.

- Create an appealing but "under-specified" hoax, with ambiguities

- Have your creation discovered.

- Find at least one champion who will actively support your hoax.

- Make people care, either positively or negatively – the ambiguities encourage interest and debate

Types

[edit]

Hoaxes vary widely in their processes of creation, propagation, and entrenchment over time. Examples include:

- Academic hoaxes:

- The Sokal affair

- The Grievance studies affair

- Art-world hoaxes:

- The "Bruno Hat" art hoax, arranged in London in July 1929, involved staging a convincing public exhibition of paintings by an imaginary reclusive artist, Bruno Hat. All the perpetrators were well-educated and did not intend a fraud, as the newspapers were informed the next day. Those involved included Brian Howard, Evelyn Waugh, Bryan Guinness, John Banting and Tom Mitford[15]

- Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960: a 1998 art world hoax, by William Boyd

- Disumbrationism: a modern art hoax

- Pierre Brassau: exposing art critics to "modern paintings" made by a chimpanzee

- Ads for Jean Freeman Gallery appeared in "Art in America" in 1970, but the art gallery and its address did not exist. It turned out to be a performance art hoax later covered in news outlets The New York Times and "Today"

- Spectra: A Book of Poetic Experiments: a modernist poetry hoax

- Ern Malley, the popular but fictitious Australian poet

- Apocryphal claims that originate as a hoax gain widespread belief among members of a culture or organisation, become entrenched as persons who believe it repeat it in good faith to others, and continue to command that belief after the hoax's originators have died or departed

- Computer virus hoaxes became widespread as viruses themselves began to spread. A typical hoax is an email message warning recipients of a non-existent threat, usually forging quotes supposedly from authorities such as Microsoft and IBM. In most cases the payload is an exhortation to distribute the message to everyone in the recipient's address book. Thus the e-mail "warning" is itself the "virus." Sometimes the hoax is more harmful, e.g., telling the recipient to seek a particular file (usually in a Microsoft Windows operating system); if the file is found, the computer is deemed to be infected unless it is deleted. In reality the file is one required by the operating system for correct functioning of the computer.

- Criminal hoax admissions, such as the case of John Samuel Humble, also known as Wearside Jack. Criminal hoax admissions divert time and money of police investigations with communications purporting to come from the actual criminal. Once caught, hoaxers are charged under criminal codes such as perverting the course of justice and wasting police time.

- Factoids

- Hoaxes formed by making minor or gradually increasing changes to a warning or other claims widely circulated for legitimate purposes

- Hoax of exposure is a semi-comical or private sting operation. It usually encourages people to act foolishly or credulously by falling for patent nonsense that the hoaxer deliberately presents as reality. A related activity is culture jamming.

- Hoax news

- Hoaxes perpetrated by "scare tactics" appealing to the audience's subjectively rational belief that the expected cost of not believing the hoax (the cost if its assertions are true times the likelihood of their truth) outweighs the expected cost of believing the hoax (cost if false times likelihood of falsity), such as claims that a non-malicious but unfamiliar program on one's computer is malware

- Hoaxes perpetrated on occasions when their initiation is considered socially appropriate, such as April Fools' Day

- Humbugs

- Internet hoaxes became more common after the start of social media. Some websites have been used to hoax millions of people on the Web[16]

- Paleoanthropological hoaxes, anthropologists were taken in by the "Piltdown Man discovery" that was widely believed from 1913 to 1953

- Protest hoaxes. Members of social movements and other political activists have often used hoaxes in order to draw attention to causes and undermine their opponents.[17]

- Religious hoaxes

- UFO hoaxes

- Urban legends and rumours with a probable conscious attempt to deceive[7]

Hoax news

[edit]Hoax news (also referred to as fake news[18][19]) is a news report containing facts that are either inaccurate or false but which are presented as genuine.[20] A hoax news report conveys a half-truth used deliberately to mislead the public.[21]

Hoax may serve the goal of propaganda or disinformation – using social media to drive web traffic and amplify their effect.[22][23][24] Unlike news satire, fake news websites seek to mislead, rather than entertain, readers for financial or political gain.[25][23]

Hoax news is usually released with the intention of misleading to injure an organisation, individual, or person, and/or benefit financially or politically, sometimes utilising sensationalist, deceptive, or simply invented headlines to maximise readership. Likewise, clickbait reports and articles from this operation gain advertisement revenue.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Wikipedia:Hoax – Wikipedia content guideline, an article about hoaxes on Wikipedia.

- Conspiracy theory – Attributing events to less-probable plots

- Counterfeit – Making a copy or imitation which is represented as the original

- Deception – Causing someone to believe something that is not true

- Email spoofing – Creating email spam or phishing messages with a forged sender identity or address

- Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds – 1841 book by Charles Mackay

- Fake memoir – Type of literary forgery

- Fake news website – Website that deliberately publishes hoaxes and disinformation

- False document – Technique employed to create verisimilitude in a work of fiction

- Fictitious entry – Deliberately incorrect entry in a reference work

- Forgery – Process of making, adapting, or imitating objects to deceive

- Half-truth – Deceptive statement

- Impostor – List of people acting under false identity

- List of hoaxes

- Literary forgery – Literary work which is deliberately misattributed to a historical or invented author

- Media manipulation – Techniques in which partisans create an image that favours their interests

- Musical hoax – Intentionally misattributed music

- Post-truth politics – Political culture where facts are considered irrelevant

- Tall tale – Story with unbelievable elements, related as if it were true and factual

- Virus hoax – Message warning of a non-existent computer virus

- Website spoofing – Creating a website, as a hoax, with the intention of misleading readers

References

[edit]- ^ Rea, Christopher; Rusk, Bruce (2017). "Translators' Introduction". The Book of Swindles: Selections from a Late Ming Collection. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 1.

- ^ Fitch, Marc E. (2013). Paranormal Nation: Why America Needs Ghosts, UFOs, and Bigfoot. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313382079 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nares, Robert (1822). A glossary; or, Collection of words ... which have been thought to require illustration, in the works of English authors. London: R. Triphook. p. 235.

- ^ a b "Merriam-Webster Dictionary: Hocus". Merriam-Webster. 2010. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ See the Hocus Pocus article for more detail.

- ^ a b Editors of the American Heritage Dictionaries (2006). More Word Histories and Mysteries: From Aardvark to Zombie. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 110. ISBN 0-618-71681-5.

- ^ a b Brunvand, Jan H. (2001). Encyclopedia of Urban Legends. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 194. ISBN 1-57607-076-X.

- ^ Brunvand, Jan H. (1998). American Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 587. ISBN 0-8153-3350-1.

- ^ Walsh, Lynda (2006). Sins Against Science: The Scientific Media Hoaxes of Poe, Twain, And Others. State University of New York Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-7914-6877-1.

- ^ Boese, Alex (2008). "What Is A Hoax?". Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ a b Walsh, Lynda (2006). Sins Against Science: The Scientific Media Hoaxes of Poe, Twain, And Others. State University of New York Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 0-7914-6877-1.

- ^ a b c Oldenburg, Ann (12 October 2009). "Director: 'Chloe and Keith's Wedding' video is a hoax". USA Today. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

But today, we can tell you: it's definitely a hoax. Chloe and Keith are actors named Josh Covitt and Charissa Wheeler. They're not married.

- ^ Watson, Ivan (10 March 2010). "Fake Russian invasion broadcast sparks Georgian panic". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Hancock, Peter (2015). Hoax Springs Eternal: The Psychology of Cognitive Deception. Cambridge U.P. pp. 182–195. ISBN 978-1107417687.

- ^ "Leicester Galleries website on Bruno Hat, accessed 28th May 2011". Leicestergalleries.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ "How serial hoaxers duped the Internet". Washington Post. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ McIntyre, Iain (2 September 2019). "Pranks, performances and protestivals: Public Events". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Bartolotta, Devin (9 December 2016), "Hillary Clinton Warns About Hoax News On Social Media", WJZ-TV, archived from the original on 4 December 2019, retrieved 11 December 2016

- ^ Wemple, Erik (8 December 2016), "Facebook's Sheryl Sandberg says people don't want 'hoax' news. Really?", The Washington Post, archived from the original on 27 February 2020, retrieved 11 December 2016

- ^ Zannettou Savvas; Sirivianos Michael; Blackburn Jeremy; Kourtellis Nicolas (7 May 2019). "The Web of False Information". Journal of Data and Information Quality. 10 (3): 4. arXiv:1804.03461. doi:10.1145/3309699.

- ^ Fallis, Don (2014), Floridi, Luciano; Illari, Phyllis (eds.), "The Varieties of Disinformation", The Philosophy of Information Quality, Synthese Library, vol. 358, Springer International Publishing, pp. 135–161, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-07121-3_8, ISBN 978-3-319-07121-3

- ^ Weisburd, Andrew; Watts, Clint (6 August 2016), "Trolls for Trump – How Russia Dominates Your Twitter Feed to Promote Lies (And, Trump, Too)", The Daily Beast, archived from the original on 31 May 2017, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ a b LaCapria, Kim (2 November 2016), "Snopes' Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors – Snopes.com's updated guide to the internet's clickbaiting, news-faking, social media exploiting dark side.", Snopes.com, archived from the original on 28 June 2020, retrieved 19 November 2016

- ^ Sanders IV, Lewis (11 October 2016), "'Divide Europe': European lawmakers warn of Russian propaganda", Deutsche Welle, archived from the original on 25 March 2019, retrieved 24 November 2016

- ^ Chen, Adrian (2 June 2015). "The Agency". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- MacDougall, Curtis D. (1958) [1940] Hoaxes. [revised ed.] New York: Dover

- Young, Kevin (2017). Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News. Graywolf Press. ISBN 978-1555977917.

External links

[edit]- The Culture Jammer's Encyclopedia

- Snopes – Urban Legends Reference Pages

- The Greatest Hoaxes of All Time Archived 24 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine – slideshow by Life magazine

- "What's All This Hoax Stuff, Anyhow?" (Bob Pease article on Electronic Design website) Archived 11 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Chloe and Keith's Wedding hoax – link to video and commentary at USA Today

- Leyendas Urbanas Archived 18 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine – Urban Legends and Hoaxes in Spanish