François Darlan

François Darlan | |

|---|---|

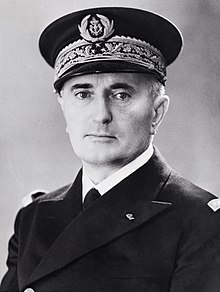

Darlan c. 1940 | |

| Deputy Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 9 February 1941 – 18 April 1942 | |

| Chief of the State | Philippe Pétain |

| Preceded by | Pierre Étienne Flandin |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| High Commissioner of France in Africa (French North Africa and French West Africa) | |

| In office 14 November 1942 – 24 December 1942 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Henri Giraud (as French Civil and Military Commander-in-chief) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan 7 August 1881 Nérac, Lot-et-Garonne, France |

| Died | 24 December 1942 (aged 61) Algiers, Alger, French Algeria |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | French Navy |

| Years of service | 1902–1942 |

| Rank | Admiral of the Fleet |

| Commands | Chief of Staff of the French Navy Edgar Quinet Jeanne d'Arc |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Médaille militaire Croix de Guerre |

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ lwi ɡzavje fʁɑ̃swa daʁlɑ̃]; 7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the École navale in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service during World War I. He was promoted to rear admiral in 1929, vice admiral in 1932, lieutenant admiral in 1937 before finally being made admiral and Chief of the Naval Staff in 1937. In 1939, Darlan was promoted to admiral of the fleet, a rank created specifically for him.

Darlan was Commander-in-Chief of the French Navy at the beginning of World War II. After France's armistice with Germany in June 1940, Darlan served in Philippe Pétain's Vichy regime as Minister of Marine, and in February 1941 he took over as Vice-President of the Council, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of the Interior and Minister of National Defence, making him the de facto head of the Vichy government. In April 1942, Darlan resigned his ministries to Pierre Laval at German insistence, but retained his position as Commander-in-Chief of the French Armed Forces.

Darlan was in Algiers when the Allies invaded French North Africa in November 1942. Allied commander Dwight D. Eisenhower struck a controversial deal with Darlan, recognizing him as High Commissioner of France for North and West Africa. In return, Darlan ordered all French forces in North Africa to cease resistance and cooperate with the Allies. Less than two months later, on 24 December, Darlan was assassinated by Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle, a 20-year-old monarchist and anti-Vichyiste.

Early life and career

[edit]Darlan was born in Nérac, Lot-et-Garonne, to a family with a long connection with the French Navy. His great-grandfather was killed at the Battle of Trafalgar.[1] His father, Jean-Baptiste Darlan, was a lawyer and politician who served as Minister of Justice in the cabinet of Jules Méline. Georges Leygues, a political colleague of his father who would spend seven years as Minister of the Marine, was Darlan's godfather.[2]

Darlan graduated from the École Navale in 1902. During World War I, he commanded an artillery battery that took part in the Battle of Verdun.[3] After the war Darlan commanded the training ships Jeanne d'Arc and Edgar Quinet, receiving promotions to frigate captain in 1920 and captain in 1926.

Thereafter Darlan rose swiftly. He was appointed Chef de Cabinet to Leygues and promoted to contre-amiral in 1929. In 1930, he served as the French Navy's representative at the London Naval Conference, and in 1932 he was promoted to vice-amiral. Subsequently, in 1934, he took command of the Atlantic Squadron at Brest. He was promoted to vice-amiral d'escadre in 1936.

Chief of the Naval Staff

[edit]In 1936, he went to London on an unsuccessful mission to persuade the Admiralty that greater Anglo-French naval co-operation was needed given the way that Germany and Italy had aligned as a result of the Spanish Civil War.[4] During the Spanish Civil War, the Front populaire government of Léon Blum leaned into a pro-Republican neutrality while Italy had intervened on the side of the Spanish Nationalists, leading to acute Italo-French tensions.[5] Blum stated that Darlan "thinks exactly as I do" about a potential Italian naval threat to France, and selected him as the next chief of staff of la Royale to replace the pro-Italian Admiral Georges Durand-Viel.[4] In addition, Darlan was considered by Blum to be loyal to the republic and Darlan had spoken in favor of the Front populaire social reforms.[4] Darlan had attracted attention within the Marine in the fall of 1936 with his advocacy of France seizing the Balearic Islands to put a stop to the Italian naval and air bases under construction there as he argued that the prospect of Italian naval and air attacks from the Balearics on French shipping was an intolerable threat.[4] Through Blum did not take up Darlan's suggestion, he did approve of him as an admiral with strong anti-Italian views, which he considered to be a refreshing contrast to Durand-Viel who advocated a Franco-Italian alliance.[4] Blum's decision in October 1936 to appoint Darlan as the next chief of the naval staff over a number of admirals who had more seniority and combat experience was controversial.[4]

He was appointed Chief of the Naval Staff from 1 January 1937, at the same time promoted to amiral. Darlan was close to Blum and the Defense Minister Édouard Daladier.[4] As head of the Navy he successfully used his political connections to lobby for a building programme to counter the rising threat from the Kriegsmarine and Regia Marina. The American historian Reynolds Salerno wrote: "While Durand-Viel was a soft-spoken, cautious administrator who sought out advice from his subordinates and deferred to his minister for major policy decisions, Darlan was an extremely self-confident, resolute admiral who monopolized every aspect of the Marine".[6] Salerno described Darlan as a conservative French nationalist who was committed to preserving France as a great power via a programe of building more warships for the Marine.[6] Darlan's political views were inclined towards the right, but he worked well with the centrist Daladier and the leftish Blum.[7]

After attending the Coronation of George VI, Darlan complained that protocol had left him, as a mere vice admiral, "behind a pillar and after the Chinese admiral".[8] In 1939 he was promoted to Amiral de la flotte, a rank created specifically to put him on equal terms with the First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy.[1]

Darlan saw the Regia Marina as the principal threat to France, and pushed very hard for a naval expansion intended to make France the dominant power in the Mediterranean Sea.[7] Germany had a population of 70 million while France had a population of 40 million. The numerical superiority of the Reich made it essential that the French transport a massive number of soldiers recruited in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia to France to allow the French Army to face the Wehrmacht on equal terms, and as such it was considered essential that France have command of the sea-lanes in the western Mediterranean.[9] Dalan argued that the pro-German orientation of Italian foreign policy made it likely that Italy would enter another world war on the side of Germany and that as such France needed a strong Mediterranean fleet to defend the sea-lanes linking Algeria to France in order to win against Germany.[9] French decision-makers believed given the numerical superiority of Germany that just as in the last world war that France would need a massive number of troops from the Maghreb in order to have a chance of victory, and without soldiers from the Maghreb France was doomed.[9] In addition, Darlan argued: "A significant part of the British and French supplies and in particular, almost all the oil extracted from the French, British and Russian oil fields in the East depend upon mastery of the Mediterranean. But above all, the Mediterranean constitutes the only communication line with our Central European allies by which material may reach them".[9] In contrast to Darlan, General Maurice Gamelin had argued for a rapprochement with Italy as he argued that a naval arms race would take away francs from the French Army.[10] Blum and Daladier chose the course advocated by Darlan and in December 1936 approved of a naval construction programme designed to make the French Mediterranean fleet the dominant fleet in the western Mediterranean.[10] In September 1938 during the Sudetenland crisis, Darlan mobilized the French Navy and placed the Marine on the highest state of alert.[11] Expecting Italy to enter any war on the Axis side, Darlan reinforced the French Mediterranean fleet.[11]

In the fall of 1938 and the winter of 1939, Darlan continued to argue for a Mediterranean strategy as he stated that France was secure behind the Maginot Line and should in the event of war go on the offensive against Italy in order to secure command of the sea in the Mediterranean.[12] In particular, Daladier who was now serving as premier, was greatly impressed with Darlan's Mediterranean strategy.[12] On 30 November 1938, demonstrations were organised by the Fascist regime in Italy demanding that France cede Nice, Corsica and Tunisia to Italy, which brought France and Italy to the brink of war.[13] The acute crisis in Franco-Italian relations in the winter of 1938-1939 served to reinforce Darlan's arguments within the French government for an offensive strategy against Italy..[13] At a meeting of the defense chiefs in January 1939, Darlan stated in the event of a war the Marine should sever the sea-lanes linking Italy to its colony of Libya while French warships should bombard Naples, La Spezia, and Pantelleria.[13] Darlan also called for the French to seize the Italian colony of the Dodecanese islands, for a bombing campaign against Italian cities and for invasions from Tunisia into Libya and France into Italy itself.[13] During the Danzig crisis, Darlan went to London on 8 August 1939 to meet the First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound, to discuss plans should the crisis end in a war.[14] It was agreed at the Darlan-Pound meeting that the French fleet should remain focused on the Mediterranean with the majority of the French fleet to be stationed at the naval bases at Toulon, Mers El Kébir and Bizerte with only one squadron to be based at Brest on France's Atlantic coast as the Royal Navy was to take responsibility for the rest of the North Atlantic and the North Sea.[14]

After the declaration of war in September 1939, Darlan became Commander-in-Chief of the French Navy. Darlan was opposed to Daladier's plans for a revived Salonika front.[15] At a meeting of the Anglo-French Supreme War Council on 22 September 1939, Darlan sided with the British in opposing Daladier's plans to take the Armée du Levant from Beirut to Thessaloniki with the aim of opening a second front in the Balkans as a way to aid Poland.[15] Darlan argued that the plans for a new Salonika Front would distract from the blockade of Germany.[15] Initially, Darlan had supported the British who believed that a naval blockade along with strategical bombing would be sufficient to defeat the Reich without any major land battles.[16] The British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, believed that a combination of blockade and strategical bombing would induce the Wehrmacht generals to overthrow Hitler and thus bring the war to a close with no major land battles involving British troops.[17] At the meetings of the Supreme War Council, Darlan along with Maurice Gamelin supported the objections of the British against the proposed expedition to the Balkans championed by Daladier and Maxime Weygand[18]

By late 1939, Darlan complained that the blockade had too many loopholes for neutral ships carrying war material to Germany and that the Allies needed a more aggressive approach.[16] In particular, Darlan noted that because of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact that Germany had access to all of the vast natural resources of the Soviet Union, which rendered the Anglo-French naval blockade rather ineffectual.[16] The Soviet Union was self-sufficient in virtually all of the natural resources needed to sustain a modern industrial economy, and German-Soviet trade defeated the purposes of the naval blockade.[16] Starting in December 1939, Darlan started to advocate an Anglo-French expedition to Scandinavia to seize the Swedish iron mines that supplied the Germany with high-grade iron that was used to make steel (the Reich had no high-grade iron mines of it own).[19] Darlan argued that it was impetrative to strike before Germany and the Soviet Union signed another economic agreement that would allow Germany to have access to Soviet iron, saying the time to deprive Germany of its access to Swedish iron was now.[19]

Darlan was one of the main advocates of a Scandinavian expedition, arguing to seize the Swedish iron mines would cause collapse of the German economy no later than the spring of 1941.[20] By January 1940, Darlan had convinced Daladier that the expedition to Scandinavia would win the war for the Allies.[21] In January 1940, Darlan called for a joint Army-Navy expedition to sail via the Arctic Ocean to seize the Petsamo province of Finland recently occupied by the Red Army even though it would almost mean war with the Soviet Union out of the hope of provoking German response, which would allow French forces to occupy northern Sweden, and hence deprive the Reich of its most important source of iron.[22] Darlan had a blasé attitude towards the prospect of a war with the Soviet Union, arguing that since the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact that it made little difference if France were at war with the Soviet Union or not.[22] The plans for a Scandinavian expedition drew strong opposition from Maurice Gamelin who argued that best place for French manpower was in defending France from the expected German invasion.[21] However, Gamelin's inability to produce a convincing alternate strategy led for Daladier to decide in favor of Darlan's recommendation.[23] Unlike the plans for a new Salonika front, the British leaders, especially the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, were very keen on an expedition to Scandinavia.[24] Likewise, Darlan supported what the French called the "Baku project" of having Anglo-French bombers based in Syria and Iraq bomb the oil fields in Baku in Soviet Azerbaijan as a way to cut Germany off from Soviet oil.[25] Darlan also supported plans for French submarines to be sent into the Black Sea to sink Soviet oil tankers.[26]

Vichy government

[edit]Armistice

[edit]Darlan was immensely proud of the French navy which he had helped to build up, and after Axis forces defeated France (May–June 1940), on 3 June he threatened that he would mutiny and lead the fleet to fight under the British flag in the event of an armistice.[27] Darlan promised Churchill at the Briare Conference (12 June) that no French ship would ever come into German hands.[28]: 62 Even on 15 June he was still talking of a potential armistice with indignation.[29] Darlan appears to have retreated from his position on 15 June, when the Cabinet voted 13–6 for Camille Chautemps' compromise proposal to inquire about possible terms. He was willing to accept an armistice provided the French fleet was kept out of German hands.[30]

On 16 June Churchill's telegram arrived agreeing to an armistice (France and Britain were bound by treaty not to seek a separate peace) provided the French fleet was moved to British ports. This was not acceptable to Darlan, who argued that it would leave France defenceless.[31] That day, according to Jules Moch, he declared that Britain was finished so there was no point in continuing to fight, and he was concerned that if there was no armistice Hitler would invade French North Africa via Franco's Spain.[27] That evening Paul Reynaud, feeling he lacked sufficient cabinet support for continuing the war, resigned as Prime Minister, and Philippe Pétain formed a new government with a view to seeking an armistice with Germany.[31]

Darlan served as the Minister of Marine in the Pétain administration from 16 June.[28]: 139–40 On 18 June Darlan gave his "word of honour" to the British First Sea Lord, Sir Dudley Pound that he would not allow the French fleet to fall into German hands.[32] Petain's government signed an armistice (22 June 1940) but retained control of the territories known as "Vichy France" after the capital moved to Vichy in early July.[28]: 139–40 General Charles Noguès, Commander-in-Chief of French forces in North Africa, was dismayed at the armistice but accepted it partly (he claimed) because Darlan would not let him have the French fleet to continue hostilities against the Axis powers.[33]

Churchill later wrote that Darlan could have been the leader of the Free French, "a de Gaulle raised to the tenth power", had he defected at this time. De Gaulle's biographer Jean Lacouture described Darlan as "the archetypal man of failed destiny" thereafter.[27][30]

Darlan, the French Navy and the British

[edit]The terms of the armistice called for the demobilisation and disarmament of the ships of the French Navy under German supervision in their home ports (mostly in the German-occupied zone). As the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill pointed out, this meant that French warships would be fully armed when they came under German control.[28]: 139–40 At Italian suggestion, the armistice terms were amended to permit the fleet to stay temporarily in North African ports, where they might potentially be seized by Italian troops from Libya.[32] Darlan ordered all ships then in the Atlantic ports (which Germany would soon occupy) to steam to French overseas possessions, out of reach of the Germans, although not necessarily of the Italians.[28]: 139–40

Despite Darlan's assurance, Churchill had remained concerned that Darlan might be overruled by the politicians, and this concern was not allayed by Darlan becoming a government minister himself. Darlan repeatedly refused British requests to place the whole fleet in British custody (or in the French West Indies). He attempted to get the British to release French warships and gave a version of the armistice terms inconsistent with what the British knew from other sources to be the case. The British lacked confidence that Darlan was being straight with them (one government adviser minuted that he had 'turned crook like the rest')[28]: 149 and believed that, even if he was sincere, he could not deliver on his promise. This belief led to the British Attack on Mers-el-Kébir (Operation Catapult), where, on 3 July 1940 the Royal Navy attacked the French fleet. The plans for "Catapult" had been drawn up as early as 14-16 June.[32] Darlan was at his house at Nérac in Gascony on 3 July, and could not be contacted.[34]

Thereafter, French forces loyal to Vichy (most of them under Darlan's command) fiercely resisted British moves into French territory, and sometimes co-operated with German forces. However, as Darlan had promised, no capital ships fell into German hands, and only three destroyers and a few dozen submarines and smaller vessels passed into German control.[28]

Darlan expected the Axis to win the war and saw it as to France's advantage to collaborate with Germany. He distrusted the British, and after the attack on Mers-el-Kébir, he seriously considered waging a naval war against Britain.[35]

1941–42: collaboration with Germany and after

[edit]

Darlan came from a republican background and never believed in the Vichyite Révolution nationale; for example, he had reservations about Pétain's clericalism.[36] However, by 1941 Darlan had become Pétain's most trusted associate. In February 1941 Darlan replaced Pierre-Étienne Flandin as "Vice President of the Council" (prime minister). He also became Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of the Interior, and Minister of National Defence, making him the de facto head of the Vichy government. On 11 February he was named Pétain's eventual successor, in accordance with Act Number Four of the constitution.[35][clarification needed]

Darlan was primarily concerned with negotiating the peace treaty that was supposed to be followed up after the armistice and saw the "Jewish Question" in France as a bargaining tool for a better peace treaty with the Germans.[37] Darlan expected the Reich to win the war, and saw safeguarding French interests in the expected German-dominated postwar world as his main duty.[37] Upon entering office, Darlan had wanted to swiftly sign a peace treaty that would see the Germans end their occupation zone in northern France and along the Atlantic coast, and was greatly disenchanted at the sluggish pace of the peace talks as he learned the partition of France imposed by the armistice was going to last years instead of a few months.[38] Like many other French people at the time, Darlan adhered to a division in outlook towards les Israélites (the term for the assimilated French Jews who had embraced the French language and culture) and les Juifs (the rather derogatory term for Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe). Darlan had complained in the 1930s that France was accepting too many Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe whom he accused of causing crime and economic problems.[39] At a cabinet meeting, Darlan stated: "The stateless Jews who have thronged to our country in the last fifteen years do not interest me. But the others, the good old French Jews, have a right to every protection we can give them. I have some, by the way, in my own family".[39] Darlan tended to be opposed to Nazi measures against the "good" French Jews while being silent against the Nazi measures against the "bad" immigrant Jews, protesting against laws that stripped the property away from French Jews while supporting the same laws against immigrant Jews.[39] In memo, Darlan wrote that his aim towards the "Jewish Question" was to "not bother the old French Jews".[39]

As a prominent figure in the Vichy government, Darlan repeatedly offered Hitler active military cooperation against Britain. Hitler, however, distrusted France and wanted it to remain neutral during his planned attack on the Soviet Union.[35]

Darlan negotiated the Paris Protocols of May 1941 with Germany, in which Germany made concessions on prisoners of war and occupation terms, and France agreed to German bases in French colonies. This last condition was opposed by Darlan's rival, General Maxime Weygand, and the Protocols were never ratified, though Weygand was dismissed at German insistence in November 1941.

However, the Germans became suspicious of Darlan's opportunism and malleable loyalties as his obstructionism mounted. He refused to provide French conscript labour.[36] After Allied forces captured French Syria and Lebanon in June–July 1941, and the German invasion of the USSR stalled before Moscow by December 1941, Darlan moved away from his policy of collaboration.[35]

Because he reported only to Pétain, Darlan exercised broad powers, although Pétain's own entourage (including Weygand) continued to wield considerable influence. In running the French colonial empire, Darlan relied heavily on the personal loyalty of key army and naval officers in the colonies to head off defection to Free France.[36]

In January 1942, Darlan assumed additional government offices.[36] But in April 1942, at German insistence, Darlan resigned his ministries, and was replaced by Pierre Laval, whom the Germans considered more trustworthy. Darlan retained several lesser posts, including that of commander-in-chief of the French armed forces.[citation needed]

Darlan's deal in North Africa

[edit]On 5 November 1942, Darlan went to Algiers to visit his son, who was hospitalised. Coincidentally, the day after his arrival, 8 November, the Western Allies invaded French North Africa.

During the night of 7–8 November, the main group of Algerian resistance (led by two cousins, Roger Carcassonne in Oran and José Aboulker in Algiers) seized control of Algiers in anticipation of the invasion. They prepared with Henri d'Astier de la Vigerie to support the expected Allied landings and met with General Mark Clark in Vichy Morocco, who provided them with weapons.[40]

They also captured Darlan. The Allies had anticipated little response from French forces in North Africa, and instead expected them to accept the authority of General Henri Giraud, sent from France to take charge. But opposition from the Vichy army continued, and no one heeded Giraud, who had no official status. To bring a quick end to the resistance and secure French co-operation, the Allies put a lot of pressure on Darlan, who released a general cease-fire (including Morocco) after two days (on 10 November). But the Americans wanted the active assistance of French forces in North Africa. Only after nine more days, once Hitler had sent troops into the formerly unoccupied zone, and under extreme pressure from the Americans, did Darlan agree that French troops in North Africa should help to defend Tunisia against rapidly arriving German reinforcements.[41]

Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied commander on the spot, recognized Darlan as commander of all French forces in the area as well his self-nomination as High Commissioner of France in Africa (head of civil government) for North and West Africa on 14 November[42][36] and Vichy forces in French West Africa joined the movement.[43]: 274 Eisenhower then reached an agreement with Darlan on 22 November to political and military co-operation.[44]

The "Darlan deal" proved highly controversial, as Darlan had been a notorious collaborator with Germany, as de facto head of the Vichy government between February 1941 and June 1942: he negotiated the Paris Protocols with Hitler, that granted the Germans military facilities in Syria, Tunisia, and French West Africa. He advocated military neutrality and collaboration with Germany, both economically and politically, in exchange for compensation from the occupier.[45]

General de Gaulle and his Free France organization were outraged; so were the pro-Allied conspirators (Géo Gras Group) who had seized Algiers. Many of them were jailed by Darlan for months. Some high American and British officials objected, and there was furious criticism by newspapers and politicians. Roosevelt defended it (using wording suggested by Churchill) as 'a temporary expedient, justified only by the stress of battle'.[43]: 261

In a secret session, Churchill persuaded an initially skeptical House of Commons. Eisenhower's recognition of Darlan was right, he said, and even if not quite right, it meant French rifles pointed not at Allies, but at Axis soldiers: "I am sorry to have to mention a point like this, but it makes a lot of difference to a soldier whether a man fires his gun at him, or at an enemy..."[43]: 275 At the time, Churchill saw Darlan rather than de Gaulle as the better French ally, saying in the same speech that "de Gaulle is no unfaltering friend of Britain".[46] On 26 November 1942 Churchill told the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden that "Darlan has done more for us than de Gaulle" while Oliver Harvey wrote in his diary: "P.M. is getting more and more enthusiastic over Darlan".[46] American historian Arthur Funk maintained that the "deal with Darlan" was misunderstood by the critics at the time as an opportunistic improvisation and claimed Darlan had been in talks with American diplomats for months about switching sides, and when the opportunity came, did so promptly.[36] American historian Robert Paxton on the contrary considers it is a thesis "based on too many post-war pleas to be credible":[45] archives showing Darlan making every effort to discourage and then thwart Allied action.[47]

The cease-fire and the "deal" were condemned by the Vichy government. Pétain stripped Darlan of his offices and ordered resistance to the end in North Africa, but was ignored. The Germans were more direct: German troops occupied the remaining 40% of France on 11 November. However, the Germans initially paused outside Toulon, the base where most of the remaining French ships were moored. Only on 27 November did the Germans try to seize the ships, but all capital ships were scuttled, and only three destroyers and a few dozen smaller ships were captured, mostly fulfilling Darlan's promise in 1940 to Churchill.[48]

Darlan refused to repeal the most aggressive laws and measures of the Vichy regime, which resulted in political prisoners remaining in concentration camps of the South. Justifying himself on military grounds, he refused to abolish the discriminatory status of Jews, restore the Crémieux Decree, or emancipate Muslims.[49][50] There were numerous and obvious indications that the American public did not support its government’s Vichy policy, that it saw Vichy’s true colors, and that it even supported de Gaulle’s Free France movement: even an American official admitted that this episode amounted to “a sordid nullification of the principles for which the United Nations were supposed to be fighting for”.[51]

Assassination

[edit]On the afternoon of 24 December 1942, French anti-Vichyiste and monarchist Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle shot Darlan in his headquarters; Darlan died a few hours later. Bonnier de La Chapelle (aged 20), the son of a French journalist, was part of a pro-monarchist group that wanted to restore the pretender to the French throne, the Count of Paris.[52]

De La Chapelle was arrested immediately, tried and convicted the next day, and executed by firing squad on 26 December.[53][54][55]

Legacy

[edit]Darlan was unpopular with the Allies – he was considered pompous, having asked Eisenhower to provide 200 Coldstream Guards and Grenadier Guards as an honor company for the commemoration of Napoleon's victory at Austerlitz. It was said that "no tears were shed" by the British over his death.[56] Harold Macmillan, who was Churchill's adviser to Eisenhower at the time of the assassination, wryly described Darlan's service and death by saying, "Once bought, he stayed bought."[1] In his memoirs of the World War Two entitled The Second World, Churchill at first portrayed Darlan in volume 2, Their Finest Hour, as an especially devious and dishonest figure, a corrupt schemer whose word was not to be trusted as a justification for the attack on Mers-el-Kébir in 1940.[57] Later on in The Hinge of Fate, Churchill portrayed the "deal with Darlan" in 1942 as a distasteful, but necessary measure to allow the success of Operation Torch.[58] At that point his picture of Darlan changed into a honorable, but misguided French patriot whose principle sin was his Anglophobia, which Churchill put down to an ancestor of Darlan's having been killed at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.[58] Churchill devoted nearly an entire page into praising Darlan's character with the clear implication he was a worthy alliance partner in North Africa.[59] The British historian David Reynolds noted that Churchill's picture of Darlan tended to change as a way to justify whatever policy he was pursuing towards France.[58]

Military ranks

[edit]| Midshipman second class | 7 August 1901[60] |

|---|---|

| Midshipman first class | 5 October 1902[61] |

| Ship-of-the-line ensign | 5 October 1904[62] |

| Ship-of-the-line lieutenant | 16 November 1910[63] |

| Corvette captain | 11 July 1918[64] |

| Frigate captain | 1 August 1920[65] |

| Ship-of-the-line captain | 17 January 1926[66] |

| Counter admiral | 19 November 1929[67] |

| Vice-admiral | 4 December 1932[68] |

| Squadron vice-admiral | 1936 |

| Admiral | 1 January 1937 |

| Admiral of the fleet | 24 June 1939[69][70] |

Decorations

[edit] Knight of the Order of Agricultural Merit: 28 July 1906[71]

Knight of the Order of Agricultural Merit: 28 July 1906[71] Officer of the Order of Maritime Merit: 19 January 1931[72]

Officer of the Order of Maritime Merit: 19 January 1931[72] Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour: 21 December 1937[73];Grand Officer: 31 December 1935[74];Commander: 31 December 1930;[75] Officer: 16 June 1920;[76] Knight: 1 January 1914[77]

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour: 21 December 1937[73];Grand Officer: 31 December 1935[74];Commander: 31 December 1930;[75] Officer: 16 June 1920;[76] Knight: 1 January 1914[77]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Korda, Michael (2007). Ike: An American Hero. New York: HarperCollins. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-06-075665-9. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Auphan, Paul; Mordai, Jacques (1959). The French Navy in World War II. Naval Institute Press. p. 10. ISBN 9781682470602.

- ^ Horne, Alistair (1993). The Price of Glory: Verdun 1916. New York: Penguin. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-14-017041-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Salerno 1997, p. 73.

- ^ Salerno 1997, p. 71-73.

- ^ a b Salerno 1997, p. 74.

- ^ a b Salerno 1997, p. 73-74.

- ^ Auphan and Mordai, p. 17

- ^ a b c d Salerno 1997, p. 78.

- ^ a b Salerno 1997, p. 77-78.

- ^ a b Salerno 1997, p. 84.

- ^ a b Salerno 1997, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Salerno 1997, p. 86.

- ^ a b Melton 1998, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Imlay 2004, p. 339.

- ^ a b c d Imlay 2004, p. 347.

- ^ Imlay 2004, p. 338.

- ^ Imlay 2004, p. 338-339.

- ^ a b Imlay 2004, p. 352.

- ^ Imlay 2004, p. 354.

- ^ a b Imlay 2004, p. 355.

- ^ a b Imlay 2004, p. 353.

- ^ Imlay 2004, p. 356.

- ^ Imlay 2004, p. 357.

- ^ Imlay 2004, p. 364.

- ^ Imlay 2004, p. 363.

- ^ a b c Lacouture 1991, p. 231

- ^ a b c d e f g Bell, P M H (1974). A Certain Eventuality. Farnborough: Saxon House. pp. 141–42. ISBN 0-347-000-10-X.

- ^ Lacouture 1991, p. 231

- ^ a b Williams 2005, pp. 325–27

- ^ a b Atkin 1997, pp. 82–86

- ^ a b c Lacouture 1991, p. 246

- ^ Lacouture 1991, pp. 229–30

- ^ Lacouture 1991, p. 247

- ^ a b c d Melka, Robert L. (April 1973). "Darlan between Britain and Germany 1940–41". Journal of Contemporary History. 8 (2): 57–80. doi:10.1177/002200947300800204. JSTOR 259994. S2CID 161469746.

- ^ a b c d e f Melton, George (1998). Darlan: Admiral and Statesman of France 1881–1942. Westport, CT: Praeger. pp. 81–117, 152. ISBN 0-275-95973-2. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Paxton & Marrus 1995, p. 75.

- ^ Paxton & Marrus 1995, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Paxton & Marrus 1995, p. 85.

- ^ Martin Gilbert, 'The Holocaust' (1986), page 482.

- ^ Paxton, Robert O. (December 2023). "The Discreet Eminence On the enduring legacy of Marshal Pétain". Harper's Magazine.

- ^ Funk, Arthur L. (April 1973). "Negotiating the'Deal with Darlan". Journal of Contemporary History. 8 (2): 81–117. doi:10.1177/002200947300800205. JSTOR 259995. S2CID 159589846.

- ^ a b c Gilbert, Martin (1986). Road to Victory: Winston S. Churchill 1941–1945. London: Guild Publishing.

- ^ "Opération "Torch", les débarquements alliés en Afrique du Nord" [Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa]. Chemins de mémoire (French Government website).

- ^ a b Paxton, Robert (1992). "O. Darlan, un amiral entre deux blocs. Réflexions sur une biographie récente" [O. Darlan, Admiral between two blocks. Reflections on a recent biography] (PDF). Vingtième Siècle, revue d'histoire. 36: 8. doi:10.3406/xxs.1992.2599.

- ^ a b Reynolds 2007, p. 330.

- ^ Paxton cites his own work Parades and politics at Vichy, Princeton University Press, 1966, p. 326-330, and the thesis of Christine Lévisse-Touzé (in French) L'Afrique du Nord: recours au secours. Septembre 1939-juin 1943, Université Paris I, 1990, p. 263, 321, 487-585.

- ^ Vaisset, Thomas; Vial, Philippe (1 September 2020). Viant, Julien (ed.). "Success or failure? The divided memory of the sabotage of Toulon". Inflexions. 45 (3). Paris, France: French Army/Cairn.info: 45–60. doi:10.3917/infle.045.0045. ISSN 1772-3760. S2CID 226424361.

- ^ "les juifs de l'Algérie coloniale". LDH-Toulon (in French). 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Kaspi, André (1971). La Mission de Jean Monnet à Alger, mars-octobre 1943 [Jean Monnet's mission to Algiers, March-October 1943]. Publications de la Sorbonne (in French). Vol. 2. éditions Richelieu. p. 101. OCLC 680978.

- ^ Neiberg, Michael (2021). When France Fell: The Vichy Crisis and the Fate of the Anglo-American Alliance. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 94.

- ^ Atkinson, Rick (2003). An Army at Dawn. Henry Holt. pp. 251–52. ISBN 9780805074482.

- ^ "Darlan Shot Dead; Assassin Is Seized". New York Times. 25 December 1942. p. 1. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Havens, Murray Clark; Leiden, Carl; Schmitt, Karl Michael (1970). The Politics of Assassination. Prentice-Hall. p. 123. ISBN 9780136862796.

- ^ Chalou, George C. (1995). The Secret War: The Office of Strategic Services in World War II. Diane Publ. p. 167. ISBN 9780788125980. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Root, Waverley Lewis (1945). The Secret History of the War, Volume 2. C. Scribner's Sons.

- ^ Reynolds 2007, p. 196.

- ^ a b c Reynolds 2007, p. 396-397.

- ^ Reynolds 2007, p. 397.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (8 August 1901). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (20 September 1902). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (22 September 1904). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (19 November 1910). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (13 July 1918). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (4 August 1920). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (19 January 1926). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (19 November 1929). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (5 November 1932). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (29 June 1939). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Le Hunsec, Mathieu (15 March 2012). "L'amiral, cet inconnu". Revue historique des armées (in French) (266): 91–107. ISSN 0035-3299.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (30 July 1906). "Ministère de l'agriculture". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (24 January 1931). "Ministère de la marine marchand". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (24 December 1937). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (1 January 1936). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (1 January 1931). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (2 September 1920). "Ministère de la marine". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (26 November 1913). "Tableaux de concours pour la Legion d'Honneur". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Atkin, Nicholas, Pétain, Longman, 1997, ISBN 978-0-582-07037-0.

- Funk, Arthur L. "Negotiating the 'Deal with Darlan'." Journal of Contemporary History 8.2 (1973): 81–117. Online.

- Funk, Arthur L. The Politics of Torch, University Press of Kansas, 1974.

- Howe, George F. North West Africa: Seizing the initiative in the West, Center of Military History, US Army, 1991.

- Hurstfield, Julian G. America and the French Nation, 1939–1945 (1986) online Archived 3 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine pp. 162–83.

- Imlay, Talbot Charles (April 2004). "A Reassessment of Anglo-French Strategy during the Phony War, 1939-1940". The English Historical Review. 119 (481): 333–372. doi:10.1093/ehr/119.481.333.

- Kitson, Simon. The Hunt for Nazi Spies: Fighting Espionage in Vichy France, (University of Chicago Press, 2008)

- Lacouture, Jean. De Gaulle: The Rebel 1890–1944 (1984; English ed. 1991), ISBN 978-0-841-90927-4

- Melka, Robert L. "Darlan between Britain and Germany 1940–41", Journal of Contemporary History (1973) 8#2 pp. 57–80 at JSTOR (subscription required).

- Paxton, Robert; Marrus, Michael (1995). Vichy France and the Jews. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804724999.

- Reynolds, David (2007). In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465003303.

- Salerno, Reynolds M. (February 1997). "The French Navy and the Appeasement of Italy, 1937-9". English Historical Review. 112 (445): 66–104. doi:10.1093/ehr/CXII.445.66.

- Verrier, Anthony. Assassination in Algiers: Churchill, Roosevelt, DeGaulle, and the Murder of Admiral Darlan (1990).

- Williams, Charles, Pétain, Little Brown (Time Warner Book Group UK), London, 2005, p. 206, ISBN 978-0-316-86127-4.

In French

[edit]- José Aboulker et Christine Levisse-Touzet, "8 Novembre 1942: Les armées américaine et anglaise prennent Alger en quinze heures", Espoir, n° 133, Paris, 2002.

- Yves Maxime Danan, La vie politique à Alger de 1940 à 1944, Paris: L.G.D.J., 1963.

- Delpont, Hubert (1998). Darlan, l'ambition perdue. AVN. ISBN 2-9503302-9-0.

- Professeur Yves Maxime Danan, République Française Capitale Alger, 1940-1944, Souvenirs, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2019.

- Jean-Baptiste Duroselle, Politique étrangère de la France:L'abîme: 1940–1944. Imprimerie nationale, 1982, 1986.

- Bernard Karsenty, "Les Compagnons du 8 Novembre 1942", Les Nouveaux Cahiers, n°31, Nov. 1972.

- Simon Kitson, Vichy et la chasse aux espions nazis, Paris: Autrement, 2005.

- Christine Levisse-Touzet, L'Afrique du Nord dans la guerre, 1939–1945, Paris: Albin Michel, 1998.

- Henri Michel, Darlan, Paris: Hachette, 1993.

External links

[edit]- 1881 births

- 1942 deaths

- Antisemitism in France

- Assassinated military personnel

- Deaths by firearm in Algeria

- Executed French collaborators with Nazi Germany

- French interior ministers

- French people murdered abroad

- People of Vichy France

- French military personnel of World War I

- French military personnel killed in World War II

- French Navy admirals of World War II

- French fascists

- Ministers of marine

- People from Nérac

- People murdered in Algeria

- Order of the Francisque recipients

- Orléanists

- The Holocaust in France

- 1940s in Algiers

- 1942 murders in Algeria

- French politicians assassinated in the 20th century

- 20th-century French politicians

- École Navale alumni

- Politicians assassinated in the 1940s

- Nazis assassinated by the French resistance

- World War II political leaders