Anarchist communism

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchist communism |

|---|

|

Anarchist communism[a] is a political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and services. It supports social ownership of property and the distribution of resources "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs".

Anarchist communism was first formulated as such in the Italian section of the International Workingmen's Association.[6] The theoretical work of Peter Kropotkin took importance later as it expanded and developed pro-organizationalist and insurrectionary anti-organizationalist section.[7] Examples of anarchist communist societies are the anarchist territories of the Makhnovshchina during the Russian Revolution,[8] and those of the Spanish Revolution, most notably revolutionary Catalonia.[9]

History

[edit]Forerunners

[edit]The modern current of communism was founded by the Neo-Babouvists of the journal L'Humanitaire, who drew from the "anti-political and anarchist ideas" of Sylvain Maréchal. The foundations of anarcho-communism were laid by Théodore Dézamy in his 1843 work Code de la Communauté, which was formulated as a critique of Étienne Cabet's utopian socialism. In his Code, Dézamy advocated the abolition of money, the division of labour and the state, and the introduction of common ownership of property and the distribution of resources "from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs". In anticipation of anarchist communism, Dézamy rejected the need for a transitional stage between capitalism and communism, instead calling for immediate communisation through the direct cessation of commerce.[10]

Following the French Revolution of 1848, Joseph Déjacque formulated a radical form of communism that opposed both the revolutionary republicanism of Auguste Blanqui and the mutualism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Déjacque opposed the authoritarian conception of a "dictatorship of the proletariat", which he considered to be inherently reactionary and counter-revolutionary. Instead, he upheld the autonomy and self-organisation of the workers, which he saw expressed during the June Days uprising, against the representative politics of governmentalism. Opposed not just to government, but to all forms of oppression, Déjacque advocated for a social revolution to abolish the state, as well as religion, the nuclear family and private property. In their place, Déjacque upheld a form of anarchy based on the free distribution of resources.[11]

Déjacque particularly focused his critique on private commerce, such as that espoused by Proudhon and the Ricardian socialists. He considered a worker's right to be to the satisfaction of their needs, rather than to keep the product of their own labour, as he felt the latter would inevitably lead to capital accumulation. He thus advocated for all property to be held under common ownership and for "unlimited freedom of production and consumption", subordinated only to the authority of the "statistics book". In order to guarantee the universal satisfaction of needs, Déjacque saw the need for the abolition of forced labour through workers' self-management, and the abolition of the division of labour through integrating the proletariat and the intelligentsia into a single class. In order to achieve this vision of a communist society, he proposed a transitionary period of in which direct democracy and direct exchange would be upheld, positions of state would undergo democratization, and the police and military would be abolished.[12]

Déjacque's communist platform outlined in his Humanisphere preceded the program of the Paris Commune, and would anticipate the anarcho-communism later elaborated by Errico Malatesta, Peter Kropotkin and Luigi Galleani.[13]

Formulation in the International Workingmen's Association

[edit]

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA) was established in 1864,[14] at a time when a formalised anarchist movement did not yet exist. Of the few individual anarchists that were influential at this time, it was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's conception of federalism and his advocacy of abstentionism that inspired many of the French delegates that founded the IWA and lay the groundwork for the growth of anarchism.[15] Among the French delegates were a more radical minority that opposed Proudhon's mutualism, which held the nuclear family as its base social unit. Led by the trade unionist Eugène Varlin, the radicals advocated for a "non-authoritarian communism", which upheld the commune as the base social unit and advocated for the universal access to education.[16] It was the entry of Mikhail Bakunin into the IWA that first infused the federalists with a programme of revolutionary socialism and anti-statism, which agitated for workers' self-management and direct action against capitalism and the state.[17]

By this time, the Marxists of the IWA had begun to denounce their anti-authoritarian opponents as "anarchists", a label previously adopted by Proudhon and Déjacque and later accepted by the anti-authoritarians themselves.[18] Following the defeat of the Paris Commune in 1871, the IWA split over questions of socialist economics and the means of bringing about a classless society.[19] Karl Marx, who favoured the conquest of state power by political parties, banned the anarchists from the IWA.[20] The anarchist faction around the Jura Federation resolved to reconstitute as their own Anti-Authoritarian International, which was constructed as a more decentralised and federal organisation.[21] Two of the IWA's largest branches, in Italy and Spain, repudiated Marxism and adopted the anti-authoritarian platform.[22]

As a collectivist, Bakunin had himself opposed communism, which he considered to be an inherently authoritarian ideology.[23] But with Bakunin's death in 1876, the anarchists began to shift away from his theory of collectivism and towards an anarchist communism.[24] The term "anarchist communism" was first printed in François Dumartheray's February 1876 pamphlet, To manual workers, supporters of political action.[25] Élisée Reclus was quick to express his support for anarchist communism,[26] at a meeting of the Anti-Authoritarian International in Lausanne the following month.[27] James Guillaume's August 1876 pamphlet, Ideas on Social Organisation, outlined a proposal by which the collective ownership of the means of production could be used in order to transition towards a communist society.[28] Guillaume considered a necessary prerequisite for communism would be a general condition of abundance, which could set the foundation for the abandonment of exchange value and the free distribution of resources.[29] This program for anarcho-communism was adopted by the Italian anarchists,[30] who had already begun to question collectivism.[31]

Although Guillaume had himself remained neutral throughout the debate, in September 1877, the Italian anarcho-communists clashed with the Spanish collectivists at what would be the Anti-Authoritarian International's final congress in Verviers.[32] Alongside the economic question, the two factions were also divided by the question of organisation. While the collectivists upheld trade unions as a means for achieving anarchy, the communists considered them to be inherently reformist and counter-revolutionary organisations that were prone to bureaucracy and corruption. Instead, the communists preferred small, loosely-organised affinity groups, which they believed closer conformed to anti-authoritarian principles.[33]

In October 1880, a Congress of the defunct International's Jura Federation adopted Carlo Cafiero's programme of Anarchy and Communism, which outlined a clear break with Guillaume's collectivist programme.[34] Cafiero rejected the use of an exchange value and the collective ownership of industry, which he believed would lead to capital accumulation and consequently social stratification. Instead Cafiero called for the abolition of all wage labour, which he saw as a relic of capitalism, and for the distribution of resources "from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs".[35]

Organizationalism vs. insurrectionarism and expansion

[edit]As anarcho-communism emerged in the mid-19th century, it had an intense debate with Bakuninist collectivism and, within the anarchist movement, over participation in the workers' movement, as well as on other issues. So in Kropotkin's anarcho-communist theory of evolution, the risen people themselves are meant to be the rational industrial manager rather than a working class organized as enterprise.[7]

Between 1880 and 1890, with the "perspective of an immanent revolution", who was "opposed to the official workers' movement, which was then in the process of formation (general Social Democratisation). They were opposed not only to political (statist) struggles but also to strikes which put forward wage or other claims, or which were organised by trade unions." However, "[w]hile they were not opposed to strikes as such, they were opposed to trade unions and the struggle for the eight-hour day. This anti-reformist tendency was accompanied by an anti-organisational tendency, and its partisans declared themselves in favor of agitation amongst the unemployed for the expropriation of foodstuffs and other articles, for the expropriatory strike and, in some cases, for 'individual recuperation' or acts of terrorism."[7]

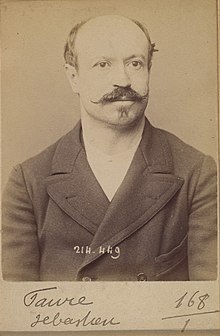

Even after Peter Kropotkin and others overcame their initial reservations and decided to enter labor unions, anti-syndicalist anarchist-communists remained, such as Sébastien Faure's Le Libertaire group and Russian partisans of economic terrorism and expropriations.[36]

Most anarchist publications in the United States were in Yiddish, German, or Russian. However, the American anarcho-communist journal The Firebrand was published in English, permitting the dissemination of anarchist communist thought to English-speaking populations in the United States.[37]

According to the anarchist historian Max Nettlau, the first use of the term "libertarian communism" was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to identify its doctrines more clearly.[4] The French anarchist journalist Sébastien Faure, later founder and editor of the four-volume Anarchist Encyclopedia, started the weekly paper Le Libertaire (The Libertarian) in 1895.[38]

Methods of organizing: platformism vs. synthesism

[edit]

In Ukraine, the anarcho-communist guerrilla leader Nestor Makhno led an independent anarchist army during the Russian Civil War. A commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine, Makhno led a guerrilla campaign opposing both the Bolshevik "Reds" and monarchist "Whites". The Makhnovist movement made various tactical military pacts while fighting various reaction forces and organizing an anarchist society committed to resisting state authority, whether capitalist or Bolshevik.[39][40]

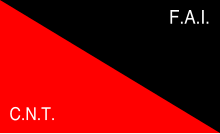

The Dielo Truda platform in Spain also met with strong criticism. Miguel Jimenez, a founding member of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI), summarized this as follows: too much influence in it of Marxism, it erroneously divided and reduced anarchists between individualist anarchists and anarcho-communist sections, and it wanted to unify the anarchist movement along the lines of the anarcho-communists. He saw anarchism as more complex than that, that anarchist tendencies are not mutually exclusive as the platformists saw it and that both individualist and communist views could accommodate anarchosyndicalism.[41] Sébastian Faure had strong contacts in Spain, so his proposal had more impact on Spanish anarchists than the Dielo Truda platform, even though individualist anarchist influence in Spain was less intense than it was in France. The main goal there was reconciling anarcho-communism with anarcho-syndicalism.[42]

Spanish Revolution of 1936

[edit]

The most extensive application of anarcho-communist ideas happened in the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution.[43]

In Spain, the national anarcho-syndicalist trade union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo initially refused to join a popular front electoral alliance, and abstention by CNT supporters led to a right-wing election victory. In 1936, the CNT changed its policy, and anarchist votes helped bring the popular front back to power. Months later, the former ruling class responded with an attempted coup causing the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).[44] In response to the army rebellion, an anarchist-inspired movement of peasants and industrial workers, supported by armed militias, took control of Barcelona and large areas of rural Spain, where they collectivized the land.[45] However, even before the fascist victory in 1939, the anarchists were losing ground in a bitter struggle with the Stalinists, who controlled the distribution of military aid to the Republican cause from the Soviet Union. The events known as the Spanish Revolution was a workers' social revolution that began during the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 and resulted in the widespread implementation of anarchist and, more broadly, libertarian socialist organizational principles throughout various portions of the country for two to three years, primarily Catalonia, Aragon, Andalusia, and parts of the Levante. Much of Spain's economy was put under worker control; in anarchist strongholds like Catalonia, the figure was as high as 75%, but lower in areas with heavy Communist Party of Spain influence, as the Soviet-allied party actively resisted attempts at collectivization enactment. Factories were run through worker committees, and agrarian areas became collectivized and ran as libertarian communes.

Anarchist Gaston Leval estimated that about eight million people participated directly or at least indirectly in the Spanish Revolution,[46] which historian Sam Dolgoff claimed was the closest any revolution had come to realizing a free, stateless mass society.[47] Stalinist-led troops suppressed the collectives and persecuted both dissident Marxists and anarchists.[48]

Post-war years

[edit]Anarcho-communism entered into internal debates over the organization issue in the post-World War II era. Founded in October 1935, the Anarcho-Communist Federation of Argentina (FACA, Federación Anarco-Comunista Argentina) in 1955 renamed itself the Argentine Libertarian Federation. The Fédération Anarchiste (FA) was founded in Paris on 2 December 1945 and elected the platformist anarcho-communist George Fontenis as its first secretary the following year. It was composed of a majority of activists from the former FA (which supported Volin's Synthesis) and some members of the former Union Anarchiste, which supported the CNT-FAI support to the Republican government during the Spanish Civil War, as well as some young Resistants. In 1950 a clandestine group formed within the FA called Organisation Pensée Bataille (OPB), led by George Fontenis.[49]

The new decision-making process was founded on unanimity: each person has a right of veto on the orientations of the federation. The FCL published the same year Manifeste du communisme libertaire. Several groups quit the FCL in December 1955, disagreeing with the decision to present "revolutionary candidates" to the legislative elections. On 15–20 August 1954, the Ve intercontinental plenum of the CNT took place. A group called Entente anarchiste appeared, which was formed of militants who did not like the new ideological orientation that the OPB was giving the FCL seeing it was authoritarian and almost Marxist.[50] The FCL lasted until 1956, just after participating in state legislative elections with ten candidates. This move alienated some members of the FCL and thus produced the end of the organization.[49] A group of militants who disagreed with the FA turning into FCL reorganized a new Federation Anarchiste established in December 1953.[49] This included those who formed L'Entente anarchiste, who joined the new FA and then dissolved L'Entente. The new base principles of the FA were written by the individualist anarchist Charles-Auguste Bontemps and the non-platformist anarcho-communist Maurice Joyeux which established an organization with a plurality of tendencies and autonomy of groups organized around synthesist principles.[49] According to historian Cédric Guérin, the new Federation Anarchiste identity included the unconditional rejection of Marxism, motivated in significant part by the previous conflict with George Fontenis and his OPB.[49] In the 1970s, the French Fédération Anarchiste evolved into a joining of the principles of synthesis anarchism and platformism.[49]

Philosophical debates

[edit]Anarchist communism supports social ownership of property.[51][52]

Rob Sparrow outlined four main reasons why anarcho-communists oppose patriotism:[53]

- The belief in equality for all people

- The use of patriotism to subjugate the working class

- The association between patriotism and militarism

- The use of patriotism to encourage loyalty to the state

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hodges, Donald C. (2014). Sandino's Communism: Spiritual Politics for the Twenty-First Century. University of Texas Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0292715646. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kinna, Ruth (2012). The Bloomsbury Companion to Anarchism. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 329. ISBN 978-1441142702. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wetherly, Paul (2017). Political Ideologies. Oxford University Press. pp. 130, 137, 424. ISBN 978-0198727859. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Nettlau 1996, p. 145.

- ^ Bolloten, Burnett (1991). The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution. University of North Carolina Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0807819067. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pernicone 1993, pp. 111–113.

- ^ a b c Pengam 1987, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre (2004) [1982]. Nestor Makhno: Anarchy's Cossack. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Edinburgh: AK Press. p. 394. ISBN 1-902593-68-5. OCLC 58872511.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray (2 February 2017). To Remember Spain: The Anarchist and Syndicalist Revolution of 1936. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021.

In anarchist industrial areas like Catalonia, an estimated three-quarters of the economy was placed under workers' control, as it was in anarchist rural areas like Aragon. [...] In the more thoroughly anarchist areas, particularly among the agrarian collectives, money was eliminated and the material means of life were allocated strictly according to need rather than work, following the traditional precepts of a libertarian communist society.

- ^ Pengam 1987, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Pengam 1987, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Pengam 1987, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Pengam 1987, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Chattopadhyay 2018, pp. 178–179; Graham 2019, p. 326; Pengam 1987, p. 67.

- ^ Graham 2019, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Graham 2019, pp. 327–328.

- ^ Graham 2019, pp. 329–332.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Graham 2019, pp. 332–333; Pengam 1987, p. 67.

- ^ Graham 2019, p. 334.

- ^ Graham 2019, pp. 334–336.

- ^ Avrich 1971, p. 23; Graham 2019, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Chattopadhyay 2018, p. 169; Pengam 1987, p. 67; Pernicone 1993, p. 28; Turcato 2019, p. 238.

- ^ Wilbur 2019, p. 214.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 107; Marshall 2008, p. 437; Pengam 1987, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 109; Graham 2019, p. 338; Pengam 1987, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Pengam 1987, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 108; Marshall 2008, p. 437; Pengam 1987, pp. 67–68; Pernicone 1993, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 108; Graham 2019, p. 338; Pengam 1987, p. 68; Pernicone 1993, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Graham 2019, p. 338; Marshall 2008, p. 437; Pengam 1987, pp. 68–69; Pernicone 1993, pp. 110–111; Turcato 2019, p. 238.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 107–108; Pengam 1987, pp. 68–69; Pernicone 1993, pp. 110–111; Turcato 2019, p. 238.

- ^ Graham 2019, p. 339; Pengam 1987, p. 69.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Graham 2019, p. 340; Pengam 1987, p. 69.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 107–108; Pengam 1987, p. 69.

- ^ Pengam 1987, p. 75.

- ^ Falk, Candace, ed. (2005). Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years, Vol. 2: Making Speech Free, 1902–1909. University of California Press. p. 551. ISBN 978-0-520-22569-5.

Free Society was the principal English-language forum for anarchist ideas in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century.

- ^ Nettlau 1996, p. 162.

- ^ Yekelchyk, Serhy (2007). Ukraine : Birth of a Modern Nation. Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3.

- ^ Townshend, Charles, ed. (1997). The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern War. Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0198204275.

- ^ Garner 2008: "Jiménez evitó ahondar demasiado en sus críticas hacia la naturaleza abiertamente marxista de algunas partes de la Plataforma, limitándose a aludir a la crítica de Santillán en La Protesta, que afirmaba que los rusos no habían sido el único grupo responsable de permitir la infiltración de las ideas marxistas, lo que iba claramente dirigido a los sindicalistas de España17. Jiménez aceptó que la Plataforma había sido un intento encomiable de resolver el eterno problema de la desunión dentro de las filas anarquistas, pero consideraba que el programa ruso tenía sus defectos. La Plataforma se basaba en una premisa errónea sobre la naturaleza de las tendencias dentro del movimiento anarquista: dividía a los anarquistas en dos grupos diferentes, individualistas y comunistas, y con ello rechazaba la influencia de los primeros y proponía la unificación del movimiento anarquista en torno a la ideas de los segundos. Jiménez afirmaba que la realidad era mucho más compleja: esas diferentes tendencias dentro del movimiento anarquista no eran contradictorias ni excluyentes. Por ejemplo, era posible encontrar elementos en ambos grupos que apoyaran las tácticas del anarcosindicalismo. Por tanto, rechazaba el principal argumento de los plataformistas según el cual las diferentes tendencias se excluían entre sí."

- ^ Garner 2008: "Debido a sus contactos e influencia con el movimiento del exilio español, la propuesta de Faure arraigó más en los círculos españoles que la Plataforma, y fue publicada en las prensas libertarias tanto en España como en Bélgica25. En esencia, Faure intentaba reunir a la familia anarquista sin imponer la rígida estructura que proponía la Plataforma, y en España se aceptó así. Opuesta a la situación de Francia, en España la influencia del anarquismo individualista no fue un motivo serio de ruptura. Aunque las ideas de ciertos individualistas como Han Ryner y Émile Armand tuvieron cierto impacto sobre el anarquismo español, afectaron sólo a aspectos como el sexo y el amor libre."

- ^ Bookchin, Murray (2 February 2017). To Remember Spain: The Anarchist and Syndicalist Revolution of 1936. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 46. ISBN 978-0297848325.

- ^ Bolloten, Burnett (1984). The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution. University of North Carolina Press. p. 1107. ISBN 978-0-8078-6043-4.

- ^ Dolgoff 1974, p. 6.

- ^ Dolgoff 1974, p. 5.

- ^ Birchall, Ian (2004). Sartre Against Stalinism. Berghahn Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-1571815422.

- ^ a b c d e f Guérin 2000.

- ^ Guérin 2000: "Si la critique de la déviation autoritaire de la FA est le principal fait de ralliement, on peut ressentir dès le premier numéro un état d'esprit qui va longtemps coller à la peau des anarchistes français. Cet état d'esprit se caractérise ainsi sous une double forme : d'une part un rejet inconditionnel de l'ennemi marxiste, d'autre part des questions sur le rôle des anciens et de l'évolution idéologique de l'anarchisme. C'est Fernand Robert qui attaque le premier : "Le LIB est devenu un journal marxiste. En continuant à le soutenir, tout en reconnaissant qu'il ne nous plaît pas, vous faîtes une mauvaise action contre votre idéal anarchiste. Vous donnez la main à vos ennemis dans la pensée. Même si la FA disparaît, même si le LIB disparaît, l'anarchie y gagnera. Le marxisme ne représente plus rien. Il faut le mettre bas; je pense la même chose des dirigeants actuels de la FA. L'ennemi se glisse partout."

- ^ Steele, David Ramsay (1992). From Marx to Mises: Post-capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-87548-449-5.

One widespread distinction was that socialism socialised production only while communism socialised production and consumption.

- ^ Mayne, Alan James (1999). From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigms. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0275961510. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ Primoratz, Igor; Pavković, Aleksandar (2007). Patriotism : philosophical and political perspectives. Aldershot, England: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-8978-2. OCLC 318534708.

Bibliography

[edit]- Avrich, Paul (1971) [1967]. The Russian Anarchists. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00766-7. OCLC 1154930946.

- Berkman, Alexander (1972) [1929]. What is Communist Anarchism?. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-22839-8. LCCN 79-188813. OCLC 573111.

- Chattopadhyay, Paresh (2018). "Anarchist Communism". Socialism and Commodity Production. Leiden: Brill. pp. 169–185. doi:10.1163/9789004377516_008. ISBN 978-9004377516.

- Dolgoff, Sam (1974). The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution. Free Life Editions. ISBN 0-914156-03-9. LCCN 73-88239.

- Esenwein, George Richard (1989). Anarchist Ideology and the Working-class Movement in Spain, 1868–1898. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520063983.

- Garner, Jason (2008). "La búsqueda de la unidad anarquista: la Federación Anarquista Ibérica antes de la II República". Germinal. Revista de Estudios Libertarios (in Spanish). No. 6. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012.

- Graham, Robert (2019). "Anarchism and the First International". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 325–342. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_19. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158605651.

- Guérin, Cédric (2000). "Pensée et action des anarchistes en France : 1950–1970" (PDF) (in French). University of Lille III. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2007.

- Kropotkin, Peter (1901). "Communism and Anarchy". Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023 – via The Anarchist Library.

- Marshall, Peter H. (2008) [1992]. Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1. OCLC 218212571.

- Nettlau, Max (1996). A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. ISBN 978-0900384899.

- Pengam, Alain (1987). "Anarcho-Communism". In Ribel, Maximilien; Crump, John (eds.). Non-Market Socialism in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 60–82. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-18775-1_4. ISBN 978-1-349-18775-1.

- Pernicone, Nunzio (1993). Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05692-7. LCCN 92-46661.

- Turcato, Davide (2019). "Anarchist Communism". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 237–248. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_13. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 242094330.

- Wilbur, Shawn P. (2019). "Mutualism". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 213–224. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_11. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 242074567.

Further reading

[edit]- Arshinov, Peter; Makhno, Nestor; Mett, Ida; et al. (2006) [1926]. The Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists. Translated by McNab, Nestor. Delo Truda – via The Nestor Makhno Archive.

- Bookchin, Murray (1978). The Spanish Anarchists. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-090607-3.

- Cafiero, Carlo (2005) [1880]. "Anarchy and Communism". In Graham, Robert (ed.). Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas. Vol. 1. Montreal: Black Rose Books. ISBN 1-55164-250-6 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Déjacque, Joseph (2012) [1854]. The Revolutionary Question. Translated by Wilbur, Shawn P. – via The Libertarian Labyrinth.

- Déjacque, Joseph (2012) [1858]. Hartman, Janine C.; Lause, Mark A. (eds.). In the Sphere of Humanity. University of Cincinnati.

- Dézamy, Théodore (1983) [1842]. "Théodore Dézamy: Philosophy of the Current Crisis". In Corcoran, Paul E. (ed.). Before Marx: Socialism and Communism in France, 1830–48. Macmillan. pp. 188–196. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-17146-0_4. ISBN 978-1-349-17146-0.

- Flores Magón, Ricardo (1977). Poole, David (ed.). Land and liberty: anarchist influences in the Mexican revolution. Montreal: Black Rose Books. ISBN 0-919-61830-8. OCLC 4916961.

- Galleani, Luigi (1982) [1925]. The End of Anarchism?. Translated by Sartin, Max; D’Attilio, Robert. Orkney: Cienfuegos Press. OCLC 10323698.

- Kinna, Ruth (December 2012). "Anarchism, Individualism and Communism: William Morris's Critique of Anarcho-communism". In Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, Dave (eds.). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 35–56. ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3.

- Kropotkin, Peter (1974) [1899]. Ward, Colin (ed.). Fields, Factories and Workshops. New York: Harper & Row. LCCN 74-9072.

- Kropotkin, Peter (2015) [1892]. The Conquest of Bread. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-141-39611-8. OCLC 913790063.

- Kropotkin, Peter (1970a) [1927]. "Anarchist Communism: Its Basis and Principles". In Baldwin, Roger Nash (ed.). Kropotkin's Revolutionary Pamphlets. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 44–78. LCCN 77-111606. OCLC 943046641.

- Kropotkin, Peter (1970b) [1927]. "Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal". In Baldwin, Roger Nash (ed.). Kropotkin's Revolutionary Pamphlets. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 114–144. LCCN 77-111606. OCLC 943046641.

- Mclaughlin, Paul (2007). Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6196-2. LCCN 2007007973.

- Malatesta, Errico (2014). Turcato, David (ed.). The Method of Freedom. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1849351447. OCLC 859185688.

- Malatesta, Errico (2016). Turcato, David (ed.). The Complete Works of Errico Malatesta. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1849352581. OCLC 974145362.

- Nappalos, Scott (2012). "Ditching Class: The Praxis of Anarchist Communist Economics". In Shannon, Deric; Nocella, Anthony J.; Asimakopoulos, John (eds.). The Accumulation of Freedom: Writings on Anarchist Economics. AK Press. pp. 291–312. ISBN 978-1-84935-094-5. LCCN 2011936250.

- Puente, Isaac (1982) [1932]. "Libertarian Communism". Anarchist Review. No. 6. Orkney: Cienfuegos Press.

- Ramnath, Maia (2019). "Non-Western Anarchisms and Postcolonialism". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 677–695. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_38. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 150357033.

- Shannon, Deric (2019). "Anti-Capitalism and Libertarian Political Economy". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 91–106. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_5. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158841066.

External links

[edit]- Anarkismo.net – anarchist communist news maintained by platformist organizations with discussion and theory from across the globe

- Anarchocommunism texts at The Anarchist Library

- Kropotkin: The Coming Revolution – short documentary to introduce the idea of anarcho-communism in Peter Kropotkin's own words