Anomaly (physics)

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

In quantum physics an anomaly or quantum anomaly is the failure of a symmetry of a theory's classical action to be a symmetry of any regularization of the full quantum theory.[1][2] In classical physics, a classical anomaly is the failure of a symmetry to be restored in the limit in which the symmetry-breaking parameter goes to zero. Perhaps the first known anomaly was the dissipative anomaly[3] in turbulence: time-reversibility remains broken (and energy dissipation rate finite) at the limit of vanishing viscosity.

In quantum theory, the first anomaly discovered was the Adler–Bell–Jackiw anomaly, wherein the axial vector current is conserved as a classical symmetry of electrodynamics, but is broken by the quantized theory. The relationship of this anomaly to the Atiyah–Singer index theorem was one of the celebrated achievements of the theory. Technically, an anomalous symmetry in a quantum theory is a symmetry of the action, but not of the measure, and so not of the partition function as a whole.

Global anomalies

[edit]A global anomaly is the quantum violation of a global symmetry current conservation. A global anomaly can also mean that a non-perturbative global anomaly cannot be captured by one loop or any loop perturbative Feynman diagram calculations—examples include the Witten anomaly and Wang–Wen–Witten anomaly.

Scaling and renormalization

[edit]The most prevalent global anomaly in physics is associated with the violation of scale invariance by quantum corrections, quantified in renormalization. Since regulators generally introduce a distance scale, the classically scale-invariant theories are subject to renormalization group flow, i.e., changing behavior with energy scale. For example, the large strength of the strong nuclear force results from a theory that is weakly coupled at short distances flowing to a strongly coupled theory at long distances, due to this scale anomaly.

Rigid symmetries

[edit]Anomalies in abelian global symmetries pose no problems in a quantum field theory, and are often encountered (see the example of the chiral anomaly). In particular the corresponding anomalous symmetries can be fixed by fixing the boundary conditions of the path integral.

Large gauge transformations

[edit]Global anomalies in symmetries that approach the identity sufficiently quickly at infinity do, however, pose problems. In known examples such symmetries correspond to disconnected components of gauge symmetries. Such symmetries and possible anomalies occur, for example, in theories with chiral fermions or self-dual differential forms coupled to gravity in 4k + 2 dimensions, and also in the Witten anomaly in an ordinary 4-dimensional SU(2) gauge theory.

As these symmetries vanish at infinity, they cannot be constrained by boundary conditions and so must be summed over in the path integral. The sum of the gauge orbit of a state is a sum of phases which form a subgroup of U(1). As there is an anomaly, not all of these phases are the same, therefore it is not the identity subgroup. The sum of the phases in every other subgroup of U(1) is equal to zero, and so all path integrals are equal to zero when there is such an anomaly and a theory does not exist.

An exception may occur when the space of configurations is itself disconnected, in which case one may have the freedom to choose to integrate over any subset of the components. If the disconnected gauge symmetries map the system between disconnected configurations, then there is in general a consistent truncation of a theory in which one integrates only over those connected components that are not related by large gauge transformations. In this case the large gauge transformations do not act on the system and do not cause the path integral to vanish.

Witten anomaly and Wang–Wen–Witten anomaly

[edit]In SU(2) gauge theory in 4 dimensional Minkowski space, a gauge transformation corresponds to a choice of an element of the special unitary group SU(2) at each point in spacetime. The group of such gauge transformations is connected.

However, if we are only interested in the subgroup of gauge transformations that vanish at infinity, we may consider the 3-sphere at infinity to be a single point, as the gauge transformations vanish there anyway. If the 3-sphere at infinity is identified with a point, our Minkowski space is identified with the 4-sphere. Thus we see that the group of gauge transformations vanishing at infinity in Minkowski 4-space is isomorphic to the group of all gauge transformations on the 4-sphere.

This is the group which consists of a continuous choice of a gauge transformation in SU(2) for each point on the 4-sphere. In other words, the gauge symmetries are in one-to-one correspondence with maps from the 4-sphere to the 3-sphere, which is the group manifold of SU(2). The space of such maps is not connected, instead the connected components are classified by the fourth homotopy group of the 3-sphere which is the cyclic group of order two. In particular, there are two connected components. One contains the identity and is called the identity component, the other is called the disconnected component.

When a theory contains an odd number of flavors of chiral fermions, the actions of gauge symmetries in the identity component and the disconnected component of the gauge group on a physical state differ by a sign. Thus when one sums over all physical configurations in the path integral, one finds that contributions come in pairs with opposite signs. As a result, all path integrals vanish and a theory does not exist.

The above description of a global anomaly is for the SU(2) gauge theory coupled to an odd number of (iso-)spin-1/2 Weyl fermion in 4 spacetime dimensions. This is known as the Witten SU(2) anomaly.[4] In 2018, it is found by Wang, Wen and Witten that the SU(2) gauge theory coupled to an odd number of (iso-)spin-3/2 Weyl fermion in 4 spacetime dimensions has a further subtler non-perturbative global anomaly detectable on certain non-spin manifolds without spin structure.[5] This new anomaly is called the new SU(2) anomaly. Both types of anomalies[4] [5] have analogs of (1) dynamical gauge anomalies for dynamical gauge theories and (2) the 't Hooft anomalies of global symmetries. In addition, both types of anomalies are mod 2 classes (in terms of classification, they are both finite groups Z2 of order 2 classes), and have analogs in 4 and 5 spacetime dimensions.[5] More generally, for any natural integer N, it can be shown that an odd number of fermion multiplets in representations of (iso)-spin 2N+1/2 can have the SU(2) anomaly; an odd number of fermion multiplets in representations of (iso)-spin 4N+3/2 can have the new SU(2) anomaly.[5] For fermions in the half-integer spin representation, it is shown that there are only these two types of SU(2) anomalies and the linear combinations of these two anomalies; these classify all global SU(2) anomalies.[5] This new SU(2) anomaly also plays an important rule for confirming the consistency of SO(10) grand unified theory, with a Spin(10) gauge group and chiral fermions in the 16-dimensional spinor representations, defined on non-spin manifolds.[5][6]

Higher anomalies involving higher global symmetries: Pure Yang–Mills gauge theory as an example

[edit]The concept of global symmetries can be generalized to higher global symmetries,[7] such that the charged object for the ordinary 0-form symmetry is a particle, while the charged object for the n-form symmetry is an n-dimensional extended operator. It is found that the 4 dimensional pure Yang–Mills theory with only SU(2) gauge fields with a topological theta term can have a mixed higher 't Hooft anomaly between the 0-form time-reversal symmetry and 1-form Z2 center symmetry.[8] The 't Hooft anomaly of 4 dimensional pure Yang–Mills theory can be precisely written as a 5 dimensional invertible topological field theory or mathematically a 5 dimensional bordism invariant, generalizing the anomaly inflow picture to this Z2 class of global anomaly involving higher symmetries.[9] In other words, we can regard the 4 dimensional pure Yang–Mills theory with a topological theta term live as a boundary condition of a certain Z2 class invertible topological field theory, in order to match their higher anomalies on the 4 dimensional boundary.[9]

Gauge anomalies

[edit]Anomalies in gauge symmetries lead to an inconsistency, since a gauge symmetry is required in order to cancel unphysical degrees of freedom with a negative norm (such as a photon polarized in the time direction). An attempt to cancel them—i.e., to build theories consistent with the gauge symmetries—often leads to extra constraints on the theories (such is the case of the gauge anomaly in the Standard Model of particle physics). Anomalies in gauge theories have important connections to the topology and geometry of the gauge group.

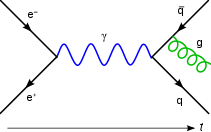

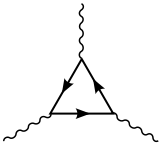

Anomalies in gauge symmetries can be calculated exactly at the one-loop level. At tree level (zero loops), one reproduces the classical theory. Feynman diagrams with more than one loop always contain internal boson propagators. As bosons may always be given a mass without breaking gauge invariance, a Pauli–Villars regularization of such diagrams is possible while preserving the symmetry. Whenever the regularization of a diagram is consistent with a given symmetry, that diagram does not generate an anomaly with respect to the symmetry.

Vector gauge anomalies are always chiral anomalies. Another type of gauge anomaly is the gravitational anomaly.

At different energy scales

[edit]Quantum anomalies were discovered via the process of renormalization, when some divergent integrals cannot be regularized in such a way that all the symmetries are preserved simultaneously. This is related to the high energy physics. However, due to Gerard 't Hooft's anomaly matching condition, any chiral anomaly can be described either by the UV degrees of freedom (those relevant at high energies) or by the IR degrees of freedom (those relevant at low energies). Thus one cannot cancel an anomaly by a UV completion of a theory—an anomalous symmetry is simply not a symmetry of a theory, even though classically it appears to be.

Anomaly cancellation

[edit]

Since cancelling anomalies is necessary for the consistency of gauge theories, such cancellations are of central importance in constraining the fermion content of the standard model, which is a chiral gauge theory.

For example, the vanishing of the mixed anomaly involving two SU(2) generators and one U(1) hypercharge constrains all charges in a fermion generation to add up to zero,[10][11] and thereby dictates that the sum of the proton plus the sum of the electron vanish: the charges of quarks and leptons must be commensurate. Specifically, for two external gauge fields Wa, Wb and one hypercharge B at the vertices of the triangle diagram, cancellation of the triangle requires

so, for each generation, the charges of the leptons and quarks are balanced, , whence Qp + Qe = 0[citation needed].

The anomaly cancelation in SM was also used to predict a quark from 3rd generation, the top quark.[12]

Further such mechanisms include:

- Axion

- Chern–Simons

- Green–Schwarz mechanism

- Liouville action

Anomalies and cobordism

[edit]In the modern description of anomalies classified by cobordism theory,[13] the Feynman-Dyson graphs only captures the perturbative local anomalies classified by integer Z classes also known as the free part. There exists nonperturbative global anomalies classified by cyclic groups Z/nZ classes also known as the torsion part.

It is widely known and checked in the late 20th century that the standard model and chiral gauge theories are free from perturbative local anomalies (captured by Feynman diagrams). However, it is not entirely clear whether there are any nonperturbative global anomalies for the standard model and chiral gauge theories. Recent developments [14] [15] [16] based on the cobordism theory examine this problem, and several additional nontrivial global anomalies found can further constrain these gauge theories. There is also a formulation of both perturbative local and nonperturbative global description of anomaly inflow in terms of Atiyah, Patodi, and Singer [17] [18] eta invariant in one higher dimension. This eta invariant is a cobordism invariant whenever the perturbative local anomalies vanish. [19]

Examples

[edit]- Chiral anomaly

- Conformal anomaly (anomaly of scale invariance)

- Gauge anomaly

- Global anomaly

- Gravitational anomaly (also known as diffeomorphism anomaly)

- Konishi anomaly

- Mixed anomaly

- Parity anomaly

- 't Hooft anomaly

See also

[edit]- Anomalons, a topic of some debate in the 1980s, anomalons were found in the results of some high-energy physics experiments that seemed to point to the existence of anomalously highly interactive states of matter. The topic was controversial throughout its history.

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ Bardeen, William (1969). "Anomalous Ward identities in spinor field theories". Physical Review. 184 (5): 1848–1859. Bibcode:1969PhRv..184.1848B. doi:10.1103/physrev.184.1848.

- ^ Cheng, T.P.; Li, L.F. (1984). Gauge Theory of Elementary Particle Physics. Oxford Science Publications.

- ^ "Dissipative Anomalies in Singular Euler Flows" (PDF).

- ^ a b Witten, Edward (November 1982). "An SU(2) Anomaly". Phys. Lett. B. 117 (5): 324. Bibcode:1982PhLB..117..324W. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(82)90728-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Wang, Juven; Wen, Xiao-Gang; Witten, Edward (May 2019). "A New SU(2) Anomaly". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 60 (5): 052301. arXiv:1810.00844. Bibcode:2019JMP....60e2301W. doi:10.1063/1.5082852. ISSN 1089-7658. S2CID 85543591.

- ^ Wang, Juven; Wen, Xiao-Gang (1 June 2020). "Nonperturbative definition of the standard models". Physical Review Research. 2 (2): 023356. arXiv:1809.11171. Bibcode:2018arXiv180911171W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.023356. ISSN 2469-9896. S2CID 53346597.

- ^ Gaiotto, Davide; Kapustin, Anton; Seiberg, Nathan; Willett, Brian (February 2015). "Generalized Global Symmetries". JHEP. 2015 (2): 172. arXiv:1412.5148. Bibcode:2015JHEP...02..172G. doi:10.1007/JHEP02(2015)172. ISSN 1029-8479. S2CID 37178277.

- ^ Gaiotto, Davide; Kapustin, Anton; Komargodski, Zohar; Seiberg, Nathan (May 2017). "Theta, Time Reversal, and Temperature". JHEP. 2017 (5): 91. arXiv:1412.5148. Bibcode:2017JHEP...05..091G. doi:10.1007/JHEP05(2017)091. ISSN 1029-8479. S2CID 119528151.

- ^ a b Wan, Zheyan; Wang, Juven; Zheng, Yunqin (October 2019). "Quantum 4d Yang-Mills Theory and Time-Reversal Symmetric 5d Higher-Gauge Topological Field Theory". Physical Review D. 100 (8): 085012. arXiv:1904.00994. Bibcode:2019PhRvD.100h5012W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.100.085012. ISSN 2470-0029. S2CID 201305547.

- ^ Bouchiat, Cl, Iliopoulos, J, and Meyer, Ph (1972) . "An anomaly-free version of Weinberg's model." Physics Letters B38, 519-523.

- ^ Minahan, J. A.; Ramond, P.; Warner, R. C. (1990). "Comment on anomaly cancellation in the standard model". Phys. Rev. D. 41 (2): 715–716. Bibcode:1990PhRvD..41..715M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.41.715. PMID 10012386.

- ^ Conlon, Joseph (2016-08-19). Why String Theory? (1 ed.). CRC Press. p. 81. doi:10.1201/9781315272368. ISBN 978-1-315-27236-8.

- ^ Freed, Daniel S.; Hopkins, Michael J. (2021). "Reflection positivity and invertible topological phases". Geometry & Topology. 25 (3): 1165–1330. arXiv:1604.06527. Bibcode:2016arXiv160406527F. doi:10.2140/gt.2021.25.1165. ISSN 1465-3060. S2CID 119139835.

- ^ García-Etxebarria, Iñaki; Montero, Miguel (August 2019). "Dai-Freed anomalies in particle physics". JHEP. 2019 (8): 3. arXiv:1808.00009. Bibcode:2019JHEP...08..003G. doi:10.1007/JHEP08(2019)003. ISSN 1029-8479. S2CID 73719463.

- ^ Davighi, Joe; Gripaios, Ben; Lohitsiri, Nakarin (July 2020). "Global anomalies in the Standard Model(s) and Beyond". JHEP. 2020 (7): 232. arXiv:1910.11277. Bibcode:2020JHEP...07..232D. doi:10.1007/JHEP07(2020)232. ISSN 1029-8479. S2CID 204852053.

- ^ Wan, Zheyan; Wang, Juven (July 2020). "Beyond Standard Models and Grand Unifications: Anomalies, Topological Terms, and Dynamical Constraints via Cobordisms". JHEP. 2020 (7): 62. arXiv:1910.14668. Bibcode:2020JHEP...07..062W. doi:10.1007/JHEP07(2020)062. ISSN 1029-8479. S2CID 207800450.

- ^ Atiyah, Michael Francis; Patodi, V. K.; Singer, I. M. (1973), "Spectral asymmetry and Riemannian geometry", The Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 5 (2): 229–234, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.597.6432, doi:10.1112/blms/5.2.229, ISSN 0024-6093, MR 0331443

- ^ Atiyah, Michael Francis; Patodi, V. K.; Singer, I. M. (1975), "Spectral asymmetry and Riemannian geometry. I", Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 77 (1): 43–69, Bibcode:1975MPCPS..77...43A, doi:10.1017/S0305004100049410, ISSN 0305-0041, MR 0397797, S2CID 17638224

- ^ Witten, Edward; Yonekura, Kazuya (2019). "Anomaly Inflow and the eta-Invariant". arXiv:1909.08775.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- General

- Gravitational Anomalies by Luis Alvarez-Gaumé: This classic paper, which introduces pure gravitational anomalies, contains a good general introduction to anomalies and their relation to regularization and to conserved currents. All occurrences of the number 388 should be read "384". Originally at: ccdb4fs.kek.jp/cgi-bin/img_index?8402145. Springer https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-1-4757-0280-4_1