Spinal board

| Spinal board | |

|---|---|

Spinal motion restriction with a long spine board | |

| Other names | |

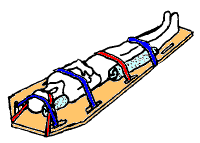

A spinal board,[4] is a patient handling device used primarily in pre-hospital trauma care. It is designed to provide rigid support during movement of a person with suspected spinal or limb injuries.[5] They are most commonly used by ambulance staff, as well as lifeguards and ski patrollers.[2][6] Historically, backboards were also used in an attempt to "improve the posture" of young people, especially girls.[7]

Due to lack of evidence to support long-term use, the practice of keeping people on long boards for prolonged periods of time is decreasing.[8][9]

Extrication uses

[edit]The spinal backboard was originally designed as a device to remove people from a vehicle. After a time people were simply kept on the spine board for transport without evidence supporting this need.[5][10]

Medical uses

[edit]A spinal board is primarily indicated for judicious use to transport people who may have had a spinal injury, usually due to the mechanism of injury, and the attending team are not able to rule out a spinal injury.[11] The person should be transferred from the board to a hospital bed as soon as possible.[11] For comfort and safety reasons, it is recommended to transfer the person to a vacuum mattress instead, in which case a scoop stretcher or long spine board is just used for the transfer.[12]

Despite its history of use, there is no evidence that backboards immobilize the spine, nor do they improve the person's outcomes. Additionally, cervical spine motion restriction has been shown to increase mortality in people with penetrating trauma and can cause pain, agitation, respiratory compromise, and can lead to the development of bedsores.[11][13]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common clinical issues found with spinal boards include pressure sore development, inadequacy of spinal motion restriction, pain and discomfort, respiratory compromise and effects on the quality of radiological imaging.[4] For this reason, some professionals view them as unsuitable for the task, preferring alternatives.[14]

It is advised that no patient should spend more than 30 minutes on a spine board, due to the development of discomfort and pressure sores.[5]

Backboards were invented to be a "highly polished surface" to move a person to an EMS bed, not to be used as spinal securing device.[citation needed]

Construction

[edit]

Backboards are almost always used in conjunction with the following devices:[citation needed]

- a cervical collar with occipital padding as needed;

- side head supports, such as a rolled blanket or head blocks (head immobilizer) made specifically for this purpose, used to avoid the lateral rotation of the head;

- straps to secure the patient to the long spine board, and tape to secure the head

Spine boards are typically made of wood or plastic, although there has been a strong shift away from wood boards due to their higher level of maintenance required to keep them in operable condition and to protect them from cracks and other imperfections that could harbor bacteria.

Backboards are designed to be slightly wider and longer than the average human body to accommodate the immobilization straps, and have handles for carrying the patient. Most backboards are designed to be completely X-ray translucent so that they do not interfere with the exam while patients are strapped to them. They are light enough to be easily carried by one person, and are usually buoyant.

Alternatives

[edit]The vacuum mattress may reduce sacral pressures compared to backboards. The conforming nature of the vacuum mattress means that people can be kept immobilized on it for longer periods of time and the immobilisation offers superior stability and comfort.[15] The Kendrick extrication device is another alternative.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ "Online training manual for Neann Long Spine Board". Neann.

- ^ a b Whatling, Shaun. Beach Lifeguarding. Royal Life Saving Society.

- ^ Sen, Ayan (2005). "Spinal Immobilisation in Prehospital Trauma Patient". Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care. 3 (3). ISSN 1447-4999.

- ^ a b Vickery, D. (2001). "The use of the spinal board after the pre-hospital phase of trauma management". Emergency Medicine Journal. 18 (1): 51–54. doi:10.1136/emj.18.1.51. PMC 1725508. PMID 11310463.

- ^ a b c Ambulance Service Basic Training 3rd Edition. IHCD. 2003.

- ^ "Red Cross Lifeguard Management Guide".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Cf. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, Chapter 3.

- ^ Sundstrøm, Terje; Asbjørnsen, Helge; Habiba, Samer; Sunde, Geir Arne; Wester, Knut (2013-08-20). "Prehospital Use of Cervical Collars in Trauma Patients: A Critical Review". Journal of Neurotrauma. 31 (6): 531–540. doi:10.1089/neu.2013.3094. ISSN 0897-7151. PMC 3949434. PMID 23962031.

- ^ Singletary, Eunice M.; Charlton, Nathan P.; Epstein, Jonathan L.; Ferguson, Jeffrey D.; Jensen, Jan L.; MacPherson, Andrew I.; Pellegrino, Jeffrey L.; Smith, William “Will” R.; Swain, Janel M. (2015-11-03). "Part 15: First Aid". Circulation. 132 (18 suppl 2): S574–S589. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000269. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 26473003.

- ^ Wesley, Karen. "Weighing the Pros & Cons of Current Spine Immobilization Techniques". JEMS. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b c National Association of EMS Physicians and American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. January 15, 2013 Position Statement: EMS Spinal Precautions and the Use of the Long Backboard

- ^ Morrissey, J (Mar 2013). "Spinal immobilization. Time for a change". Journal of Emergency Medical Services. 38 (3): 28–30, 32–6, 38–9. PMID 23717917.

- ^ "The Evidence Against Backboards". EMS World. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Tasker-Lynch, Aidan. "Spinal Boards do NOT work". 18 (1). Emergency Medicine Journal: 51–54.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Luscombe, MD; Williams, JL (2003). "Comparison of a long spinal board and vacuum mattress for spinal immobilisation". Emergency Medicine Journal. 20 (5): 476–478. doi:10.1136/emj.20.5.476. PMC 1726197. PMID 12954698.

- ^ The trauma handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004. p. 37. ISBN 9780781745963.